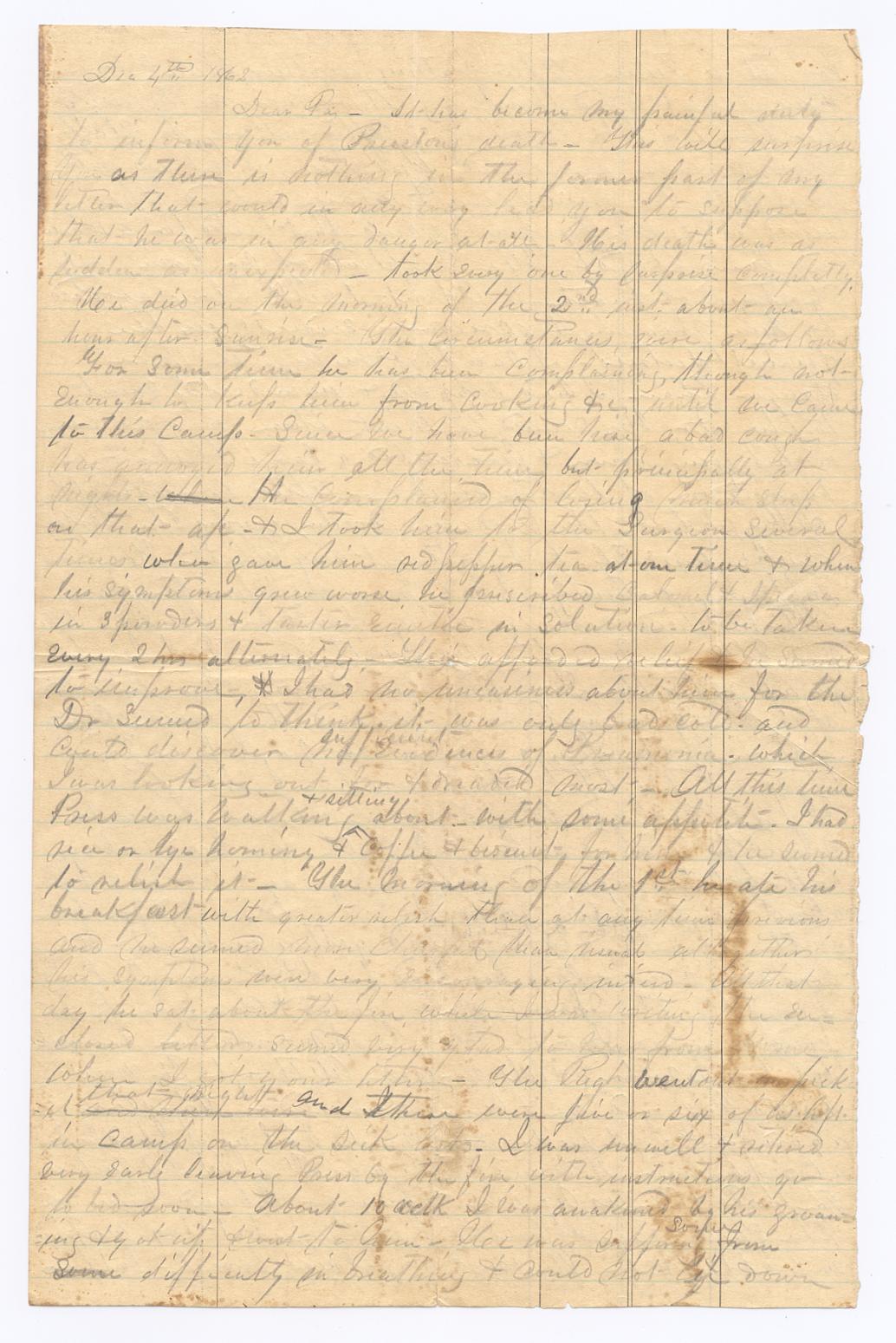

Item description: Letter, 4 December 1862, from Ruffin Thomson, 18th Mississippi Infantry Regiment, to his “Pa” (William H. Thomson). In the letter, Thomson informs his father of the death of his slave, Preston (“Press”).

More about Ruffin Thomson:

Ruffin Thomson was the oldest child and only son of William H. Thomson and Hannah Lavinia Thomson. He studied at the University of Mississippi and the University of North Carolina, leaving school in 1861 to enter the Confederate Army, serving as a private until February 1864, when he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Confederate Marine Corps. After the Civil War, he studied medicine in New Orleans and began a practice in Hinds County. In 1873, he married Fanny Potter. In 1888, he went to Fort Simcoe, Washington Territory, as clerk to the Yakima Indian Agency, hoping to recover his failing health, but instead died soon after his arrival.

[Transcription available below images.]

Item citation: From the Ruffin Thomson Papers #3315, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Item transcription:

Camp near Fredercksburg, Va.

December 4, 1862

Dear Pa,

It has become my painful duty to inform you of Preston’s death. This will surprise you, as nothing in the former part of my letter would in any way lead you to think that he was in any danger at all. The death was as sudden as unexpected – took everyone by surprise completely. He died on the morning of the 2nd just about an hour after sunrise. The circumstances were as follows:

For some time he had been complaining, though not enough to keep him from cooking, until we came to this camp. Since we have been here a bad cough has annoyed him all the time, but principally at night. He complained of losing much sleep on that account, so I took him to the surgeon several times, who gave him red pepper tea at one time, and when his symptoms became worse, he prescribed calomel and ipecac in three powders, and tartar emetic in solution to be taken every two hours alternately. This afforded relief, and he seemed to improve. I had no uneasiness about him, for the doctor seemed to think it was only bad cold, and could discover no sufficient evidence of pneumonia, which I was looking out for, and dreaded most. All this time Press was walking and sitting about, with some appetite. I had rice or lye hominy and coffee and biscuit for him, and he seemed to relish it. The morning of the first he ate his breakfast with greater relish than at any time previous, and he seemed more cheerful than usual. Altogether his symptoms were very encouraging indeed. All that day he sat about the fire while I was writing the enclosed letter, seemed very glad to hear from home when I got your letter. The regiment went on picket that night, and there were five or six of us left in camp on the sick list. I was unwell, and retired very early, leaving Press by the fire, with instructions to go to bed soon. About ten o’clock I was awakened by his groaning, and got up and went to him. He was suffering some from difficulty in breathing, and could not lie down long at a time. After putting another blanket over him I went to bed, thinking there was no necessity for the doctor until morning.

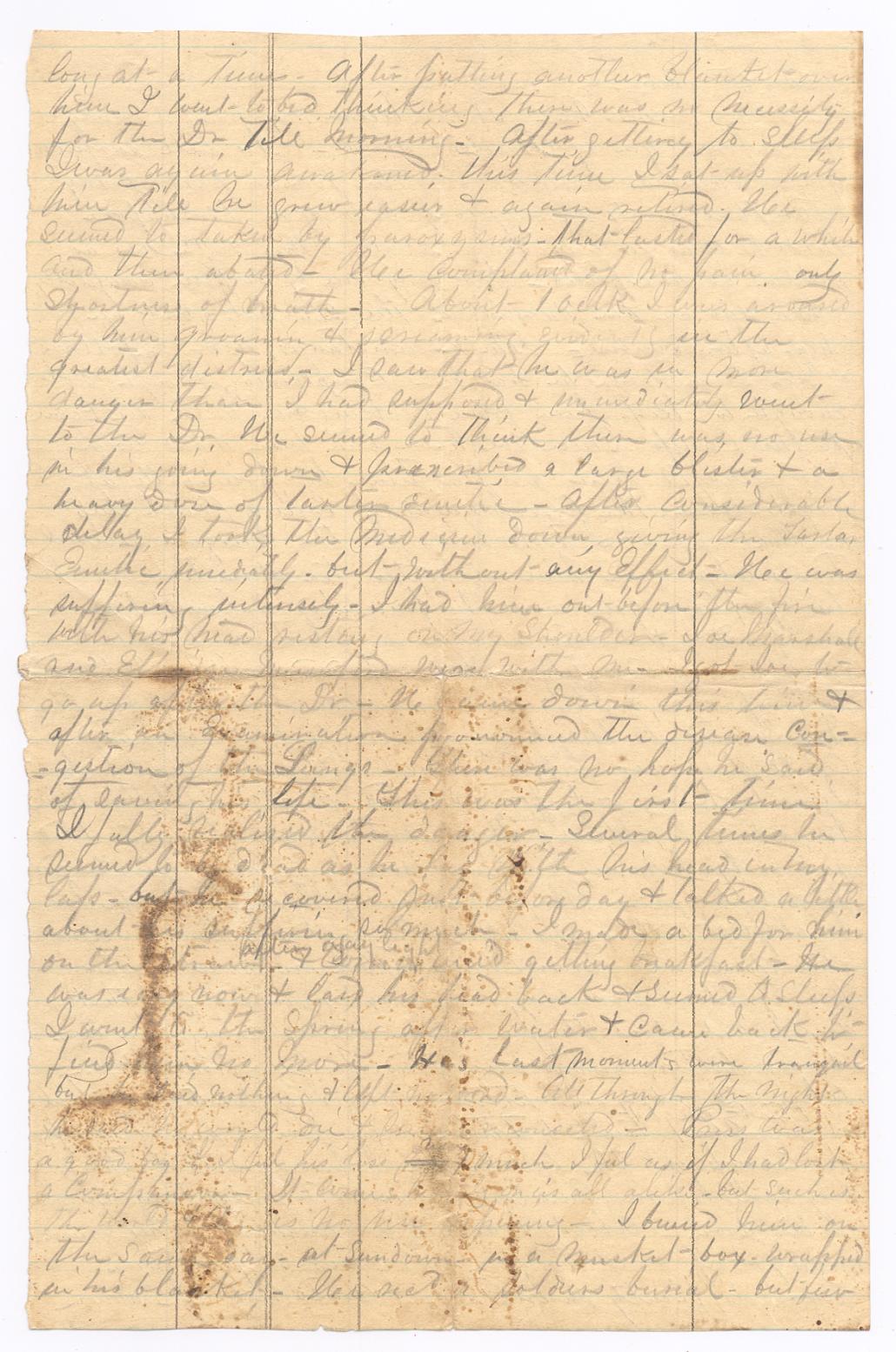

After getting to sleep I was again awakened. This time I sat up with him till he grew easier, and again retired.

He seemed to be taken by paroxysms that lasted for a while and then abated. He complained of no pain, only a shortness of breath. About ten o’clock I was aroused by his groaning and screaming, evidently in the greatest distress. I saw that he was in more danger than I had supposed, and immediately went to the doctor. He seemed to think there was no use in his going down, and prescribed a large blister, and a heavy dose of tartar emetic. After considerable delay I took the medicine down, giving the tartar emetic immediately, but without any effect. He was suffering intensely. I had him out before the fire with his head resting on my shoulder. Joe Marshall and Eldridge Mumford were with me. i got Joe to go up after the doctor. He came down this time, and after an examination pronounced it congestion of the lungs. there was no hope, he said, of saving his life. This was the first time I fully realized the danger. Several times he seemed to be dead as he lay with his head in my lap, but he recovered just before day, and talked a little about his suffering so much. I made a bed for him after daylight, on the straw, and commenced getting breakfast. He was easy now, and laid his head back and seemed to sleep. I went to the spring after water, and came back to find him no more.

His last moments were tranquil, but he said nothing, left no word. All through the night he said he would die, and seemed reconciled. I feel as if I had lost a companion. It comes hardly on us all alike, but such is the world, and there is no use in repining. I buried him on the same day, at sundown, in a musket box, wrapped in his blanket. He received a soldier’s burial, but a few

[The rest of letter is missing.]