The image of Rameses the ram sneers out from all manner of University of North Carolina memorabilia. His angry glare can be spotted on shirts, hats, keychains and bumper stickers. Of course, most Tar Heels know that there are really two different Rameses that represent the school at events both sporting and non-sporting. The story of the live Rameses, a Horned Dorset Sheep who attends home Carolina football games with Carolina blue horns, is fairly well-known. In 1924, the head of the Carolina cheerleaders, Vic Huggins, suggested buying a ram mascot to support star player Jack “The Battering Ram” Merritt. Rameses the First was purchased for $25 and the lineage has stayed in the same family all the way up to today, with Rameses XXII serving as the incumbent.

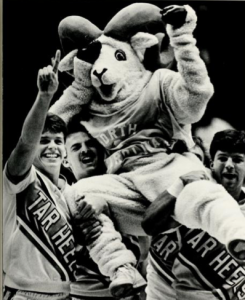

The story of the Rameses mascot, a human student inside an anthropomorphic ram costume, is less famous but equally important to the story of Carolina spirit. In 1988, students at UNC expressed interest in getting a Rameses mascot that could attend indoor events (such as basketball games) and help promote spirit across the campus and surrounding communities. At the time, UNC was the only school in the ACC without a costumed mascot. When the first Rameses costume premiered during the 1987-88 season, reactions were lukewarm.

The first costume was designed locally and featured horns made out of clay, which made the costume head heavy and difficult to move for the student inside. This student—the first to play Rameses—was senior Eric Chilton from Mount Airy, NC. The ram costume also wore a friendly expression, which some students felt wasn’t a strong representation of UNC’s tough and talented sports teams. In the October 21, 1988 edition of The Daily Tar Heel, a senior named Mike Isenhour was quoted to say, “I definitely think that we should get a new one. [The mascot] looked real wimpy. If there is going to be a new one, it should definitely be meaner.”

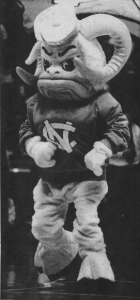

Students wanted the mascot to look more like the familiar face of Rameses seen on the UNC logo—with a tougher and more determined expression on his face. The new costume was designed by Stage Craft, a Cincinnati based company that also designed the Demon Deacon costume for Wake Forest University.

The newly designed Rameses costume premiered at the January 1989 basketball game versus NC State. He was designed to mirror the Rameses of the school logo, with a fierce scowl on his face, a Carolina blue jersey and a small hat.

The new mascot, the true identity of which was cloaked in secrecy, was elected from 12 people who auditioned. He attended both cheerleading camp and mascot camp for training. The mascot (not identified by name in the January 30, 1989 edition of the DTH), explained how acting worked when inside the costume. “Emotions have to be expressed with hand and body movements,” he said, noting that all movements had to be exaggerated.

This version of costumed Rameses was more popular than the original and became a crowd-pleasing addition to both athletics and community events. This version remained in active service until the late 1990s, when the costume was updated to the current design familiar to UNC students of today. This new design achieved a desired middle-ground between the happy-go-lucky initial design and the grumpy Rameses of the 1990s.

Today’s Rameses was designed to look muscular and intimidating and he has become a familiar sight at Carolina sporting events.

In 2007, Jason Ray was the cheerleader assigned to perform as Rameses at events. On March 23, 2007, he was struck by a car outside of the cheerleaders’ hotel in New Jersey. UNC were preparing for the Sweet Sixteen game against USC at the time. Ray died of his injuries on March 26, 2007 and his organ donation saved several lives. He was an honors student set to graduate that May with a degree in Business and a minor in religious studies.

The long tradition of UNC adapting Rameses to changing times has continued to the modern era. On October 23, 2015 an addition was made to the Carolina mascot team with the debut of Rameses Jr. (or “RJ”).

Rameses Jr. looks different from his older brother, with blue horns, blue eyes, a less muscular physique and a friendlier facial expression. RJ was created to take on some of the mascot’s responsibilities because Rameses is in very high demand for public events. He was designed to increase the appeal of Rameses to young children, as he has a softer and less scary look. He can help broaden community outreach and serve as a good ambassador for the youngest Tar Heels.

Rameses, along with RJ and his ovine cousin Rameses XXII, continue to serve as strong representatives for the Tar Heel community and are a huge part of the spirit of the university.