On Saturday, November 9, 2013, UNC celebrated homecoming when the Tar Heels hosted the University of Virginia. In the early years of their rivalry, UNC and UVA played on or near Thanksgiving Day. This years’ game marked the 118th meeting between the two schools going back to 1892—when they meet, the unusual can happen and often does. Morton Collection volunteer/contributor Jack Hilliard takes a look at a few highlights from 118 games played so far. After some fact checking, I threw in a little extra about the early years.

It is called the “South’s Oldest Rivalry” and it began with two games in 1892—the first played in Charlottesville on October 22, that Virginia won by the score of 30 to 18, the second played a month later in Atlanta on November 26 won by the Tar Heels 26 to 0. The following year, on November 30, 1893, the two teams began a series of Thanksgiving Day games that continued until 1939, with a few exceptions.

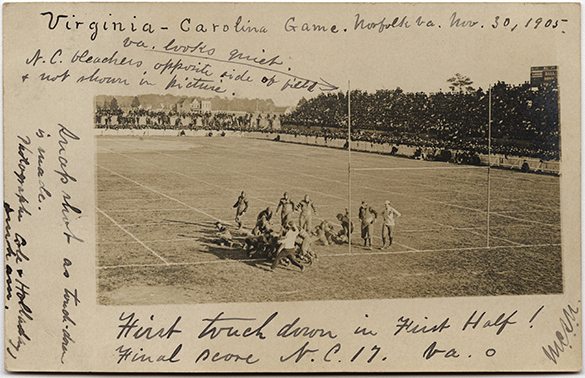

After the 1892 game at Atlanta, Carolina was able to win only three times in the next twenty—including a 17-0 victory at Richmond in 1905. The Tar Heel’s low point came in 1912 when the Cavaliers won 66 to 0 on a snowy day. Virginia dominated the series prior to World War I, boasting a 17-5-1 record.

The teams did not play against each other in 1899, 1906, and 1909. For 1899, according to the News and Observer, “bad feelings engendered” in the previous year’s game caused “all athletic relations between the two institutions” to be severed shortly after the game. Virginia accused UNC of having professionals on its team, which UNC denied. In 1906 there was a dispute between the schools about which rules to follow with the introduction of new college football rules that year—making the above 1905 UNC/UVA photograph all the more historically important as it was their last to be played before the forward pass.

All of the contests between 1893 and 1916 took place in Richmond, except for 1900, which Norfolk hosted. Because of the lopsidedness of the series during the pre-WWI era, the Tar Heels 7-to-0 win at Richmond in 1916 and their 6-0 victory in the first game played at Chapel Hill in 1919 (when the series resumed after the war) have often been added to many “greatest wins lists.” Going into the 1916 game, Carolina had lost eight games in a row with Virginia and, according to author Ken Rappoport, winning had become an “impassioned vendetta.” On November 30, 1916 before 15,000 fans in rainy Richmond, Tar Heel Bill Folger ran 52 yards through right tackle for the game’s only touchdown. George Tandy kicked the extra point to cap a Tar Heel win for the ages.

There were two exceptions to the Virginia/North Carolina Thanksgiving game day: 1900 when UNC and Georgetown fought to a 0-0 tie for the “Southern championship,” and 1901 when UNC played at Clemson. The Cavaliers and Tar Heels games for those years occurred five days prior to the holiday.

Following the 1916 win, celebrations broke out in Richmond and in Chapel Hill. Raby Tennent, a member of the ’16 Tar Heels, remembered being carried on the shoulders of Tar Heel fans around the field in Richmond, and when the team returned to Chapel Hill, fans met them at the bottom of South Hill and carried them to Emerson Field where a huge bonfire was ignited. That 1916 win has become the stuff of legends. Author Thomas Wolfe even included the game in his book The Web and the Rock. In Wolfe’s fictionalized account, UNC became Pine Rock and Virginia became Madison. Raby Tennent became Raby Bennett.

Three seasons would pass before the two teams met again. On Thanksgiving Day, November 27, 1919, the two schools played on Emerson Field—the first time the teams played in Chapel Hill. Carolina beat Virginia 6 to 0 before 2,400 cheering Tar Heel fans. Three more UNC–UVA games on Emerson Field, in 1921, 1923, and 1925, proved that Carolina needed a bigger facility. Hundreds of fans had to be turned away.

When Virginia came to Chapel Hill for their contest on November 24, 1927 “it was a whole new ball game.” On Thanksgiving Day, Carolina met Virginia at brand new Kenan Memorial Stadium. During a pre-game ceremony, John Sprunt Hill presented the facility on behalf of the donor William Rand Kenan, Jr., while Governor Angus W. McLean accepted on behalf of the State of North Carolina. Following the ceremony, to the delight of 30,000 cheering fans and Virginia Governor Harry F. Byrd, they played the game. The headline on the front page of the following day’s Greensboro Daily News read, “Carolina Wins A Close Tilt From Virginia 14-13: New Stadium Dedicated.”

Carolina’s victory had come on the toe of placekicker Garrett Morehead.

When the two teams returned to Charlottesville on Thanksgiving Day, November 29, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge and his wife Grace, along with Mrs. Woodrow Wilson were at Lambeth Field for a 24 to 20 Tar Heel victory. The Carolina win streak would continue until November 24, 1932 when Virginia beat the Tar Heels for the first time in new Scott Stadium.

A new Carolina win streak started in 1933 and continued until Thanksgiving Day, November 20, 1941… which was actually the third Thursday in November. (Six days later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt would declare the fourth Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day and seventeen days later, a Pearl Harbor event would change the world forever). But on this day, Carolina and Virginia would meet for the 43rd time and 24,000 fans turned out.

Many came to see Virginia’s 19-year-old sensation Captain “Bullet” Bill Dudley.

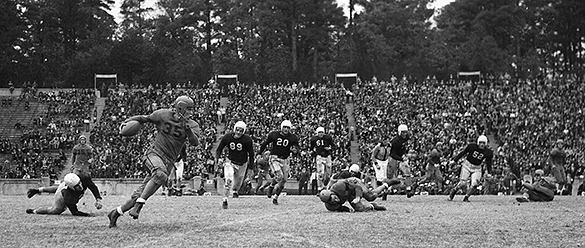

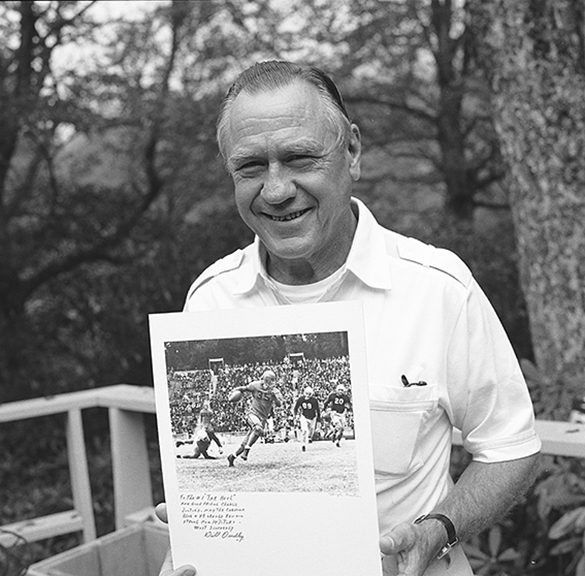

The stage was set for photographer Hugh Morton to take one of his most famous, and one of his most-often reproduced photographs. With three minutes remaining in the third quarter, and leading by a score of 14 to 7, Virginia had the ball on its own 21 yard-line . . . third down and eleven yards to go for a first down. Bill Dudley drops back in punt formation . . . but he doesn’t kick, instead he runs the ball around right end, picking up blockers along the way, as Morton frames and shoots. The run covers 79 yards and makes the score 21 to 7.

Novelist and journalist Burke Davis’ title for the picture, “I’m Coming, Virginia,” was also the title of a popular swing tune from the era. The final score that day was Virginia 28, Carolina 7. Of Virginia’s 28 points Bill Dudley scored 22. His pass to Bill Preston accounted for the other six. He gained 215 yards on the ground and completed six passes for 117 yards. John Derr, Sports Editor of the Greensboro Daily News started his account of the game with the line: “What’s a six-letter word meaning football powerhouse? The answer: D-U-D-L-E-Y” In a 1973 interview, UNC football great Charlie Justice said Bill Dudley was the greatest runner he had ever seen.

Starting in 1942 and continuing through 1949, Carolina would beat Virginia seven times, losing only in 1944. The years 1946 to 1949 are known as the “Justice Era” and rightly so. No time in Carolina football history has even come close to what was accomplished during those years. Justice led the Tar Heels to four historic wins over Virginia during the era. In so doing he gained 727 yards on the ground and threw 11 touchdown passes. The Greensboro Daily News headlines tell the story:

- 1946: Justice Tops 49-14 Attack

- 1947: Choo Choo Scores Twice As Tar Heels Win Easily

- 1948: Justice Runs Wild in Final Contest

- UNC-Chapel Hill tailback Charlie Justice (#22) running with ball at a UNC vs Virginia football game played at Kenan Stadium on November 29, 1947. Also in the scene are #48 UNC Blocking Back Don Hartig, #60 Virginia Right End Robert Weir, #23 UNC Wingback Jim Camp, and #60 UNC Right Guard Sid Varney.

Charlie Justice played his final varsity game in Kenan Stadium in perfect football weather on November 26, 1949—a game against Virginia in front of 48,000 fans. His 14-yard touchdown run in the second quarter was the winning margin in the 14 to 7 final score. Carolina would get an invitation to play Rice in the 1950 Cotton Bowl. The headline in the November 30th “Alumni Review” read: “Justice, Weiner Spark Tar Heel Win, 14-7.”

A three-game Tar Heel letdown followed the “Justice Era,” but wins in ’53 through ’56 got the team back on track. The game in 1955 was unique in that only 9,000 fans showed up in a cold, dreary Kenan Stadium. One of the 9,000 was photographer Hugh Morton.

If the 1956 Carolina – Virginia game had been a Broadway play, the following pre-kickoff announcement would have been in order: “At this afternoon’s performance, the part of Charlie Justice will be played by Ed Sutton.”

He was that good, that day. 16,000 fans in windy Scott Stadium saw Sutton lead the Tar Heels to three scores in the third period to secure a 21 to 7 win. During that crucial period, Sutton carried the ball four times for 94 of his 136 yards on the ground. He caught three passes for 40 yards giving him a primary hand in advancing the ball 134 of the 201 yards traveled for the Tar Heels’ three scores.

When Carolina returned to Scott Stadium on November 10, 1962, they were again in a five game winning streak against the Cavaliers. On that day, Tar Heel sophomore Ken Willard was featured in an 11 to 7 win. An event took place prior to the kickoff that day the likes of which had never taken place and hasn’t taken place since. Charlie Justice was introduced to the crowd and presented an award naming him “Virginia’s All Time Opponent.” The plaque presented to Justice reads in part:

The University of Virginia presents to Charles Justice, UNC ’50, on the occasion of the 67th renewal, 1962, of the University of Virginia vs. the University of North Carolina football game, the oldest continuous series in the South, for the greatest single performance by a UNC player in this series. In 1948 at Scott Stadium you finished the greatest season of your college career in the following manner: Rushing – 167 yards on 15 carries; Passing – 87 yards on 4 completions of 6 attempts; Punting – 5 times for 40.1 average; Touchdowns – 2 on runs of 80 and 50 yards; TD Passes – 2 on passes of 40 and 31 yards. Score – UNC 34 – UVA 12. In four UVA-UNC games you gained 727 yards and scored on passes for 11 touchdowns. The University of Virginia salutes the Carolina Choo Choo, our all-time opponent.

From 1974 until 1982 Carolina dominated the series, but following the win in Scott Stadium in 1981, the Tar Heels would suffer a drought at that storied facility until 2010. The loss there in 1996 was devastating.

There was Orange Bowl talk in the air as Head Coach Mack Brown’s sixth ranked Tar Heels rolled into Charlottesville for a game on November 16, 1996. The 9 and 1 Heels took charge of the game from the beginning, as a packed Scott Stadium Virginia crowd and a few hundred or so Tar Heels looked on. As the fourth quarter was ticking away and leading 17 to 3, Carolina seemed headed for a game-clinching score. With the ball at the Cavalier nine, quarterback Chris Keldorf dropped back in the shotgun as five Tar Heel receivers flooded the end zone. Keldorf first looked for tailback Leon Johnson but he was tied up blocking an on-rushing linebacker. Just then flanker Octavus Barnes seemed to come open on a crossing pattern and Keldorf let fly. Virginia defensive back Antwan Harris stepped in front of Barnes, made the pick and was away on a 95-yard score. Following the PAT, the score was 17 to 10 and the momentum had shifted. Over the next few minutes, the 35-degree afternoon got even colder for that few hundred Tar Heels as Virginia rallied for another touchdown tying the score at 17. Then with just over two minutes left, Virginia had the ball at their own 44. As overtime loomed, Virginia quarterback Tim Sherman rifled a long pass over the middle for Germane Crowell who was covered by Robert Williams and Omar Brown. All three went for the ball and for a split second it looked like Brown had intercepted, but Crowell took the ball away. It was a Virginia first down at the Carolina 15. All Virginia had to do was run a couple of plays and then have Rafael Garcia kick a 32-yard field goal for the win. Ironically Harris and Crowell were both from North Carolina.

As the Wahoos stormed the field in celebration, things got beyond ugly real quick. Bottles, cans, oranges, and ice rained down on those few Tar Heels as they tried to get out of the stadium. Coach Brown feared for the safety of his players, his staff, and that small band of Carolina supporters as security guards in the area causally watched the proceedings. When Coach Brown finally got to the media room, he chose not to mention the unsportsmanlike conduct of the Virginia fans. Instead, he said, “I am absolutely sick. It is a miserable feeling to lose this football game. But—I am proud of these guys. We’ll bounce back.” The 1996 Tar Heels did bounce back . . . finishing the season 10 and 2 and beating West Virginia in the Gator Bowl.

When the Cavaliers came into Kenan Stadium this year, they were facing a three game Tar Heel win streak in the series, and as we said in the beginning, the unusual can and often happens when these two meet on the gridiron.

So, when was the last time you saw a wide receiver complete a touchdown pass to a quarterback or when did you see one team return a punt and an intercepted pass for a score? When did you see a quarterback run, pass and receive for touchdowns? How about a game with 18 total penalties for 147 yards and 5 calls for too many players in the backfield? Or can you remember a time when one team had three players named T.J., with teammates named A.J., R.J., and J.J. and with the opposition featuring players named C.J., E.J., and D.J.? Well the answer to all of the above played out on Saturday, November 9, 2013 at the 118th meeting between the University of Virginia and the University of North Carolina. By the way, Carolina won the game 45 to 14.

One final unusual note. A check of this year’s game program indicated that Tar Heel quarterback Marquise Williams’ jersey number was 12, but when he took the field he was wearing jersey number 2 as a tribute to his friend and mentor Bryn Renner who was injured in the game with NC State last weekend. Renner, UNC starting quarterback, would normally wear jersey number 2.

Only time will tell what might happen when the Hoos and the Heels meet for game 119.

I found seven errors on the wikipedia page on the rivalry (linked in the first paragraph) related game days for the years up to and including 1942, and Jack informed me after posting that there are several other mistakes for game locations for the years following. A North Carolina Collection staff member with a wikipedia membership is going to be submitting changes for these very soon. If you discover any mistakes please let us know in a comment to this post and I’ll see that they get submitted, too. If any of the mistakes/corrections impact the story above, I’ll correct the post and note the change in a comment. Crowd sourcing is a great way to set things right!

During today’s (10/25/14) UNC – Virginia game, the ACC (TV) Network did a short look-back at the history of this rivalry. The piece included Morton pictures #3 and #5 included in this 2013 post.