Just a quick note to let you know that Series 3, and all the gorgeous, meditative splendor contained therein, is now available and included in the online finding aid for the Morton collection. (Note that the URL for the finding aid has changed, but the old link will redirect you to the new one). Note also that this is the first series to include 35mm slides in its inventory (we’re working on adding the slides for Series 1 & 2 retrospectively). Enjoy!

Category: Behind the Scenes

Digital collection at 3,000+ items!

We’ve been particularly active over the past few weeks adding images to the Hugh Morton Digital Collection, which now contains more than 3,000 items. The influx is due to the fact that 1) our new digitization assistant Sam Leonard has really hit the ground running, and 2) we’ve started scanning 35mm slides in earnest. (Slides go a bit faster due to automated scanning and because we’re often able to cut-and-paste a lot of the descriptive information).

Many of the most recent additions, including the beautifully-composed image above, have been from Morton’s nature photography. (Speaking of which, processing on Series 3, Nature & Scenic, is now finished — so be on the lookout for a major addition to the Morton finding aid in the near future). We’re adding new items every day, but as of this moment the digital collection can be browsed by 419 different names, 253 different locations, and (whoa!) 951 different subjects.

Just wanted to remind you of this remarkably varied and ever-growing resource, and to encourage you, as always, to give us your feedback on the images and on the work we’re doing.

Thank you for visiting

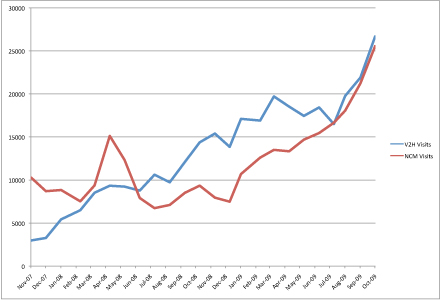

On November 1st, A View to Hugh quietly celebrated its 2nd birthday and during its years of life, this blog has received many visitors. So in this holiday season, we’d like to thank you for being a regular or occasional visitor. Have you ever wondered how many others of you in the blogosphere have been to this site during the first two years? Well, 323,012, if web statistics can be believed!

“How many visits has A View to Hugh received in two years?” would seemingly be an easy question to answer, but it isn’t. Let’s use an analogy to show why. You may take a trip to see family and stay with them for the holidays. If so, let’s say during your stay that you go to the grocery store, the shopping mall, church, and a friend’s house, and that each time you left each of those places you went back to your family’s house, your primary place of visitation.

When you return home and people ask you what you did for the holiday, you would likely say something like, “I visited my family”—that is, you made one trip to visit your family. But if Webalizer, a Web usage statistics program, was keeping tabs on your comings and goings, you went to your family’s house five times—your first arrival and each time you went back to your primary visitation place. Every time you entered your family’s front door would be counted as a “hit.” (In other words, if your family’s house was the home page for a View to Hugh, you made five “hits.”) So, our 323,012 total includes not only initial hits on the blog’s home page, but all hits to the home page.

Counting all those hits is useful to people managing Web servers. For those more interested in gauging readership, however, that tally is meaningless — especially since we know that it includes hits made by computers “crawling” Web sites, such as Google indexing for faster search results. To counter that hyperinflated number, Webalizer tallies “visits,” defined as “a sequence of requests from a uniquely identified client that expired after a certain amount of inactivity.” (The are a host of other issues related to Web statistics, but for fear of putting you to sleep, if you want to read more I’ll refer you to Wikipedia and Google where you may search the terms “Web analytics” and “Web statistics” some restless night).

Going back to the example of visiting your family: once you got there and entered any door, all your subsequent departures and returns, running in and out of the front and back doors, etc., would all be counted as one “visit” after you left their home and didn’t return for a predetermined length of time.

If you recorded all of your family visits over the course of your life, you could make a chart to see how they fluctuated over time. That’s what the chart above illustrates for A View to Hugh: the trend for the number of visits during our first two years (blue line) in comparison to our sister blog, North Carolina Miscellany (red line). At the end of two years we’ve surpassed 25,000 visits per month. That number is still inflated compared to the actual number of individual people reading the blog. (Ever read an entry on your computer at work then check it out again at home? There’s two visits!) What the chart does show without a doubt is the continual growth of interest in A View to Hugh, the library’s most frequently visited blog. And for that, we again express our deep appreciation to you, our readership.

P.S. If you did venture into deeper reading about Web analytics, the chart above uses the “total entry pages” calculation.

P.P.S. Happy holidays!

Morton project awarded NCHC grant

We’ve just gotten some exciting news! I’m pleased to share that the North Carolina Collection has been awarded a grant by the North Carolina Humanities Council to support a web publishing project entitled Worth 1,000 Words: Essays on the Photographs of Hugh Morton. The grant funds will be used exclusively to hire a group of scholars and writers to produce thirteen essays (1,000-1,500-words long, based on 3-5 images), highlighting some of the predominant themes represented in the Hugh Morton photographic collection. The essays will be published online as part of this very blog, A View to Hugh. The plan is for a new essay to be posted approximately bi-weekly between January and July, 2010.

We’ve just gotten some exciting news! I’m pleased to share that the North Carolina Collection has been awarded a grant by the North Carolina Humanities Council to support a web publishing project entitled Worth 1,000 Words: Essays on the Photographs of Hugh Morton. The grant funds will be used exclusively to hire a group of scholars and writers to produce thirteen essays (1,000-1,500-words long, based on 3-5 images), highlighting some of the predominant themes represented in the Hugh Morton photographic collection. The essays will be published online as part of this very blog, A View to Hugh. The plan is for a new essay to be posted approximately bi-weekly between January and July, 2010.

We think that the essays produced through the Worth 1,000 Words project will greatly enhance the discoverability of the collection, providing historical and cultural context and analysis of Hugh Morton’s fantastic images, while also demonstrating the value of visual resources for research and education. From the very beginning, we envisioned this project as interactive, hoping to take full advantage of the blog format. Our authors will not be writing into a void — you, as readers, will be able to comment, respond, object, ask questions . . . instead of just sitting there as static documents, the essays will provide jumping-off points for conversation, reflection, and exploration of our state’s culture and history.

We are thrilled that the Humanities Council has agreed to support this somewhat non-traditional publishing project, and would like to take this opportunity to express our appreciation to them!

View a list of essay authors and topics after the jump.

Continue reading “Morton project awarded NCHC grant”

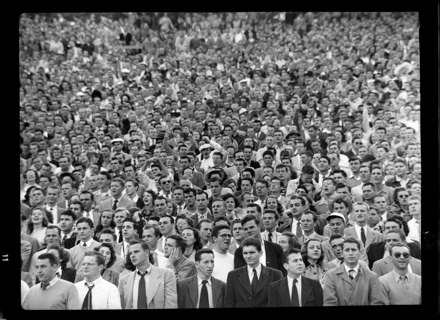

Series 2 (People & Events) available!

You knew Hugh Morton photographed legendary North Carolinians including Terry Sanford, Michael Jordan, Billy Graham, Andy Griffith, and Charles Kuralt; Azalea Queens and musicians of all stripes; and prominent national figures from John F. Kennedy to Al Gore. You definitely knew that he photographed Luther H. Hodges (NC Governor 1954-1961, and likely Morton’s most-photographed person, except for perhaps his family).

But, did you also know that Morton photographed both the Prince of Wales and Queen Elizabeth II? What about Ed Sullivan, or Rich Little? Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, and Shirley Chisholm? And how about Newt Gingrich with a black bear? (A die-hard Democrat himself, Morton did in fact take pictures of some Republicans — Gingrich, Reagan, Nixon, and Helms, to name a few). Did you know he took striking portraits of rural people living in the NC mountains during the 1940s-1950s? And shot at least four different Cherokee Chiefs?

This is just a tiny morsel of the feast of riches that await you in Series 2 of the Morton Collection, now included in the online finding aid and available for in-person exploration. This is the largest series (oh, how I hope) and definitely the most difficult to process — take note that subseries 2.6, “People, Identified,” contains more than 700 different named individuals!

Take a look, and — as always — give us your feedback on what/how we’re doing.

Morton digital collection update

The Morton digital collection has now surpassed 2,000 items! (This 1960 image of John F. Kennedy and New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner just happened to be the 2,000th image added — I like to think they are applauding our efforts).

Want to be alerted as additional Morton photos are uploaded/updated? You can now “subscribe” to the Morton collection via an RSS feed. Note that you will need to have an account with a “feed reader,” such as Google Reader or Bloglines, to use the service. You’ll probably also have to clear out a few rounds of images that are not actually new to the collection, but are new to your reader. Once you’re up-to-date, you’ll only see those that are being newly added or updated.

Speaking of which — since launching the digital collection, we have received 165 comments, almost all of which have contained useful identifying information for Morton photographs in the digital collection. While that’s definitely A LOT, the comments have come from a very small number of people. We want to hear from you! Search or browse the collection by name, location, subject, or decade, then click on “feedback” at the top of the item page to share your knowledge.

Color and Places: Hugh Morton Photographs in the North Carolina Cancer Hospital

Sometimes you have to make exceptions. A little more than a year ago, I was contacted by the designers assigned to decorate the interior of the then-under construction (and now newly opened) NC Cancer Hospital. They were seeking Hugh Morton photographs of the North Carolina landscape to be made into very large panels for public areas of the hospital. This was a great opportunity to place some of Hugh Morton’s photographs in highly visible locations within a prominent and important facility, and to assist our sister institution. The problem was, a little more than year ago, we were a little less than knowledgeable about what photographs were where in the collection. (That is one of the reasons the collection was closed to researchers until very recently). What to do?

We made an exception. I explained the status of the collection and its limited access at that point, but also asked the designer to go through Morton’s published books for images that we could try to find or approximate. Once they compiled that list, I turned it over to Elizabeth, who combed through photographs she could access to find suitable images. The design firm made their selections, Elizabeth turned over the material to the Carolina Digital Library and Archives scanning technician, and then we waited a year to see the results.

Earlier this month, Elizabeth and I had the opportunity to tour the building and see the installations. To say it is a beautiful building is not saying enough, and Morton’s photographs are wonderful splashes of color and place that contribute to the overall atmosphere inside.

The photographs you see here illustrate a few of those installations. In the photograph above, Elizabeth stands next to a very long panoramic composite mural that repeats slices of several Morton images. Below is the lobby and information desk inside the main entrance (featuring a Morton mountain panorama).

Here’s a couple of installations behind reception desks. Sorry . . . the hospital is designed to let in lots of the outside light and views, so it was impossible to photograph during the day without getting reflections!

Shown above with her back to the camera is our tour guide Ellen de Graffenreid, Director of Communications & Marketing for the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. (Thank you, Ellen!)

If this next image isn’t too tiny on your computer screen, you can play “Where’s Elizabeth?”!

It was particularly satisfying to tour this impressive facility and see how Hugh Morton’s photographs add to the overall aesthetic of the building, especially since he was a victim of cancer himself.

Morton digital collection ONLINE, your input requested

Well, we’ve been hinting about it for some time, and now, I’m SO VERY ECSTATIC to say that the Hugh Morton digital collection is finally available on the web! I can barely contain myself.

We’re really excited to make this tool available, not only because we’ve put so much work into it, but because it provides the most direct access to Hugh Morton’s work yet. As of today, there are nearly 1,500 images in the digital collection — while this is A LOT, it’s of course only a small percentage of the Morton collection as a whole. Certain topical areas are more heavily represented than others at this point, simply because we haven’t finished processing the collection yet! We’ll be adding batches of new images regularly over the next year.

Take ‘er for a spin and let us know what you think! (Be sure to play with the 3-D Wall option, which you can activate by clicking on “View in 3D” above the thumbnail images in your search results, and take advantage of our great new image viewer by zooming in and out, clicking and dragging, and expanding and contracting the viewing area). We really do want your input, on ease of use, searchability, appearance, and of course, the images themselves. Tell us if you see something identified incorrectly or incompletely. Tell us what you’d like to see added to the digital collection. Tell us how great (or un-great) we are. You can do this either by leaving comments here on the blog, or by using our online feedback form.

Some of our plans for further developing the digital collection include: adding lots more images; adding a Google map, via which you can browse selected images geographically; and linking together all the Morton access tools (the finding aid, the blog, and the digital collection).

Special thanks go out to David Meincke (our student assistant, intrepid digitizer and gifted metadata-provider) and library staff members Kim Vassiliadis, who did the original design work, and Andy Jackson, who finalized the design and handled the behind-the-scenes computery stuff. They all did great work, and are great to work with. We hope you’ll join us in celebrating this important Morton project milestone.

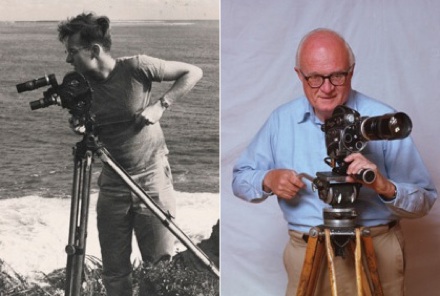

Morton the "movie man"

Note from Elizabeth: This post was written by Kyla Sweet-Chavez, a graduate student in the School of Information and Library Science here at UNC and an employee of Wilson Library. Kyla is an experienced filmmaker and film archivist, and we’re very lucky to have her as a member of the “Morton team,” processing the motion picture films.

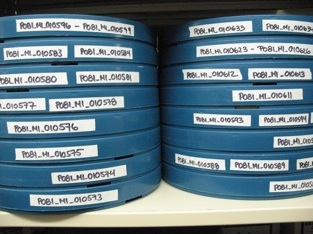

You can tell a lot from what a person has left behind, or perhaps you can just conjecture a lot. I never met Hugh Morton, but as a student assistant working on processing his film collection, I visit with him each workday. As I work my ways through the cans of film, I’ve come up with some words that I think could describe him:

Dedicated: There are boxes and boxes of film and most fall within several categories: Grandfather Mountain; Mildred the bear; Hawks and Hang Gliding; (37 variations on the) Grandfather Mountain 30-second spot; Highland Games. Morton obviously had a passion for his part of the world and didn’t often stray from it cinematically.

Thorough: Morton was a film archivist’s dream, labeling most of his boxes and cans with exactly what he shot and even making value judgments: “Ravens–good” or “Hawk, Reject.” He kept many of the films in their original boxes, which I’ve photocopied, so archivists of the future can make informed preservation decisions.

Dogged: Morton knew what he wanted. Notes and letters were often included to the film labs and TV stations, telling them exactly how his film should be printed or broadcast. He must have been on a few VIP Customer lists (and that of the USPS), so many films did he send off to the lab. He seemed to want his films to reach a broad audience. Films he sent to TV stations included typed-up perfectly timed narration to “help” them deliver his message. Many prints are in cans that have been returned by TV stations and schools from around the nation who showed his films.

You might think a film archivist sits around watching films all day but truthfully, I haven’t seen any of the Morton films in motion. I take the film from its can, inspect its overall condition, do some cleaning or repairing as necessary and if the film is unmarked, try to determine what it’s about and when it was made. (Kodak and Dupont had a system to date their film stock, using series of symbols imprinted on the edge of the film, which is how I determine the date if it isn’t marked on the can or leader). Surprisingly, many of the films from the 1970s look worse than those from the 1950s. An element of their chemicals made them “fade to magenta,” leaving them pink and washed out.

So, when can you see the Morton collection on YouTube? It’s a long journey from the original film to an online streaming copy and realistically, most won’t make that journey. The film has to be in good shape with minimal shrinkage, thoroughly cleaned and repaired, head and tail leader attached and then digitized. Doesn’t sound like much, but when you’re dealing with over 1000 films, even the most basic processing like I do takes time.

But one of the best parts of archives work is the feeling that you have accomplished something tangible. Even as Thorough and Dedicated and Dogged as Morton was, there were still a few messes to clean up, and going from this:

to this:

is incredibly satisfying. I think Morton would be pleased.

–Kyla Sweet-Chavez

The Greens of Summer?

Maybe only photographers would think of this question, but if Paul Simon’s verdant lyric about Kodachrome giving us “the greens of summer” was true, then why, oh why, was Fujichrome invented? At the risk oversimplification, let’s take a look at that question. After all, in his own way, Hugh Morton did!

Maybe only photographers would think of this question, but if Paul Simon’s verdant lyric about Kodachrome giving us “the greens of summer” was true, then why, oh why, was Fujichrome invented? At the risk oversimplification, let’s take a look at that question. After all, in his own way, Hugh Morton did!

The demise of Kodak’s Kodachrome film has made the media rounds recently, and soon after the announcement I thought of writing a post about it (because Morton first used Kodachrome in the early 1950s).

Then, we rediscovered a set of 35mm slides that Morton made where he photographed several subjects with three different films, including Kodachrome. Two of those scenes are represented here as side-by-side scans. Morton’s approach was likely loading three cameras with three different films, setting up a tripod, then swapping out the cameras to make three separate exposures. He picked several scenes until he completed the three rolls of film, then processed all three rolls and compared the results, scene by scene.

To keep this from turning into a complicated photography lesson, let’s just note that manufacturers make different films with different “extended sensitivities.” That means that one film may be more sensitive to reds and yellows, for example, and another film may be more sensitive to greens and blues. This is the case between Kodachrome and Fujichrome, and Kodachrome and Ektachrome. Can you see the differences between the films in the two examples?

When the news of Kodachrome’s death first came out, I had my natural kicked-in-the-gut reaction I get when another hallmark of film photography comes to its fateful end. A friend and I were ruefully exchanging emails discussing Kodachrome’s death blow, and I asked, “When is the last time you shot Kodachrome?” For both of us, the answer was quite a long time ago—so long ago that neither of us could remember precisely. In fact, digital photography has meant that I haven’t shot any type of film in about five years.

One of the standout benefits of digital photography over film photography is its ability to compensate for different types of lighting or adjust the rendering of colors in a particular scene from exposure to exposure, rather than from roll to roll. Depending on your camera and/or imaging software, you can make one exposure, then walk to your computer and easily create variations from that one image that would look similar to all three of Morton’s film examples—and more. This is one more reason that digital photograhy is supplanting film photography, and a contributing factor to the end of Kodachrome’s fabled history.