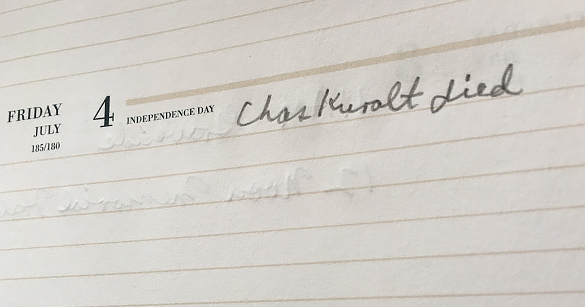

Early on the morning of Friday, July 4, 1997 we heard the sad news from New York that Tar Heel Charles Bishop Kuralt had died of heart disease and complications from lupus, an inflammatory disease that can affect the skin, joints, kidneys and nervous system. Four days later, a memorial service was held in Chapel Hill. On this, the twentieth anniversary of Kuralt’s passing, Hugh Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard recalls that day when a group of North Carolina’s finest gathered to celebrate the life of “CBS’ poet of small-town America.”

Charles really had the common touch. He was so genuine and sincere. I really believe he was the most loved, respected and trusted news personality in television. —Hugh Morton

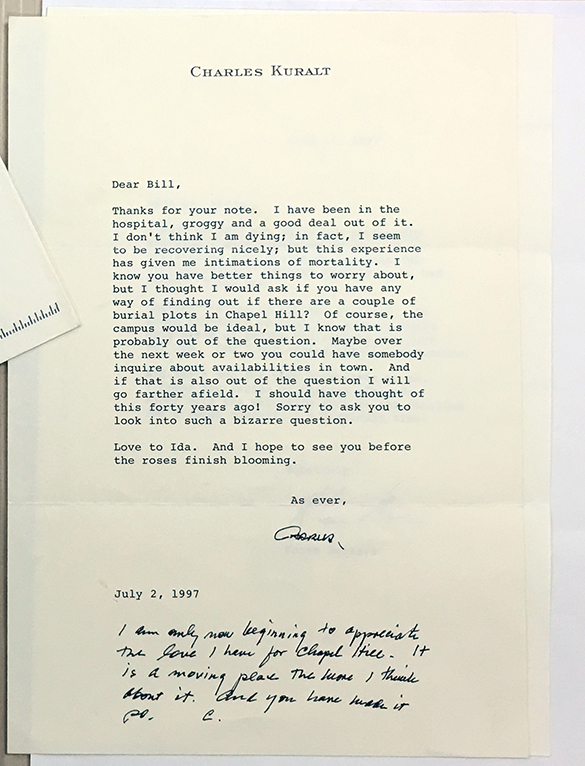

Shortly before noon on Tuesday, July 8, 1997 the old bell in South Building on the UNC campus rang for one minute. The bell is seldom used, reserved for marking such rare occasions as the installment of a new chancellor. Earlier that morning Charles Kuralt was laid to rest in the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery, the place where he wanted to be buried on the campus he loved. On July 2, two days before he died, Kuralt had sent his friend Dr. William Friday a note seeking help in securing the spot.

“I seem to be recovering nicely; but this experience has given me intimations of mortality. I know you have better things to worry about, but I thought I would ask if you have any way of finding out if there are a couple of burial plots in Chapel Hill . . . I should have thought of this forty years ago! Sorry to ask you to look into such a bizarre question.”

Before Friday got the note, he got a phone call. It was 6:00 a.m. on July 4th. Kuralt’s assistant Karen Beckers was on the line.

“I’ve called you because I must tell you that Charles is gone.”

Beckers told Friday about the note he would be getting. Friday and Chapel Hill Town Manager Cal Horton met at the cemetery with a map and determined that Chapel Hill resident George Hogan had several plots. Friday then called Hogan and explained his situation. Hogan’s reply: “No, I won’t sell them, but I’ll give Charles two.” Turns out Hogan had worked for the Educational Foundation at UNC when Kuralt was editor of The Daily Tar Heel.

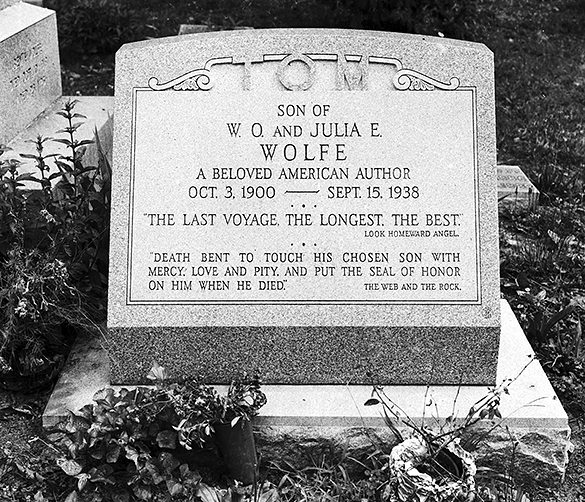

Kuralt now rests in peace near the center of the old cemetery near the gravesites of former UNC President Francis Venable and botany professor William Coker. Not far away lie the graves of others who made Tar Heel history: former UNC System President Frank Porter Graham, playwright Paul Green, and UNC Institute of Government founder Albert Coates.

Said Friday, “He’s where I felt, and the others felt, he would like to be.” Friday then added, “While he’s here with former presidents, he’s also here with the home folks of Chapel Hill.” Charles’ brother Wallace said: “This is home for him.”

Following the private ceremony at the gravesite, people filed past the site all day. Piles of flowers filled the spot where a future marker would be placed. A teary-eyed Dan Rather, then anchor of the CBS Evening News, left the burial site emotionally shaken. “I’m here in sympathy and support of his family. He gave himself to America, and he gave it everything he had.”

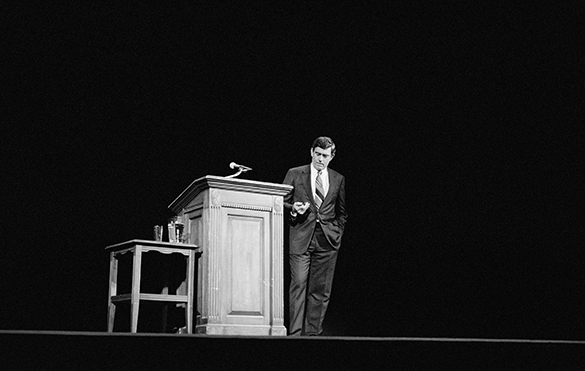

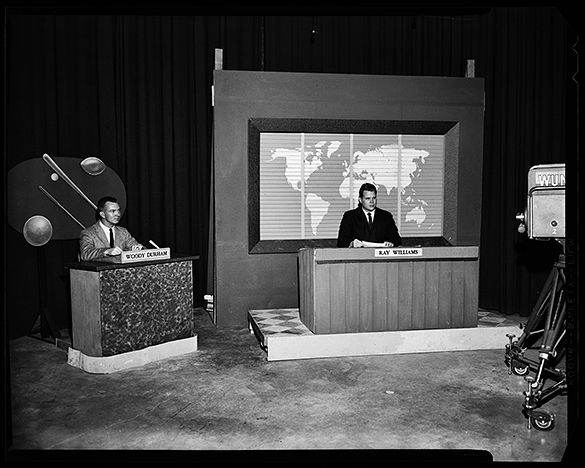

Shortly after the service at Old Chapel Hill Cemetery, more than 1,600 people packed Memorial Hall for a celebration of Kuralt’s life, with UNC Chancellor Michael Hooker presiding. WUNC-TV’s cameras were there to send the signal out across the Tar Heel state. Television personality Charlie Rose and WUNC-TV’s Audrey Kates Bailey anchored the broadcast.

The Memorial Hall stage was filled with an illustrious group of North Carolinians who came to share their friendships with Charles. The group included UNC Chancellor Michael Hooker, North Carolina Governor Jim Hunt, Kuralt’s special friend Hugh Morton, former UNC presidents William Friday and C.D. Spangler Jr, and Kuralt’s friend, composer Loonis McGlohon. The North Carolina Symphony’s Brass Ensemble was also on hand to perform segments from North Carolina is My Home, which Kuralt wrote and performed with McGlohon. McGlohon performed “The Farmer” segment that he called his favorite.

“The world knew Charles as one of the most respected and trusted newsmen of this generation, a master storyteller and a tour guide to the back roads of our nation,” said Chancellor Hooker. “The university knew him as a stalwart alumnus who never forgot his roots—whether it meant talking to our budding journalists or giving his time and effort on behalf of the School of Social Work to help promote his late father’s profession. He was a kind and generous man who never hesitated to lend his alma mater a hand however and whenever possible. He will be greatly missed.”

Morton told the standing-room only crowd at Memorial Hall, “I begged him to cancel everything and come to the mountains and sleep all day or fish all day, whatever it would take to restore his health.” Kuralt said he had too much to do.

Morton wasn’t surprised when he got a call telling him that Kuralt had died. Less than two months earlier on May 10, Hugh Morton met with Kuralt at Belmont Abbey College. It was probably their last time together. Kuralt was the commencement speaker and received an honorary degree. McGlohon also received an honorary degree that day, along with Catholic theologian and author, the Reverend Terrence Kardong, and the Reverend David Thompson, Bishop of the Charleston diocese. Kuralt had been diagnosed with lupus and his treatment regimen had taken a severe toll.

Through his world travels, Charles Kuralt never forgot his North Carolina roots. Governor Jim Hunt called Kuralt North Carolina’s storytelling ambassador, then added, “He was born on the coast, grew up in the Piedmont, loved the mountains, but he belonged to America. He was a fine reporter. But when he started telling us America’s stories, we smiled and sometimes cried when we saw the goodness.”

In July 1997, television personality Charlie Rose was hosting an interview program on Public Broadcasting (PBS), so it was a natural for the North Carolina native to co-anchor the TV coverage of the Charles Kuralt memorial broadcast on the University’s Public Broadcasting station WUNC-TV. Rose called Kuralt “a genuine American hero.”

“There was almost no one who didn’t know him. People would say ‘I was always wondering when you would show up.’” Then with a smile Rose added. “There was one exception, a woman Kuralt walked up to interview asked him to leave two quarts of milk, thinking he was the milkman.”

“All of us, when we heard the story (of Kuralt’s death) wanted to say ‘Stop—one more story, one more conversation. Introduce me to one more person that reflects America. Give me one more gentle reminder of who we are and what the great fabric of this nation is about.’ ”

Former UNC System President Dr. William Friday said, “No matter where he was in the world, he would call Chapel Hill and ask whether the dogs were still chasing the squirrels across campus and the flowers still blooming.”

When UNC System President C.D. Spangler, Jr. got to the podium to add his remarks, he opened with these words: “To Charles and all his family here, I say welcome back to Chapel Hill.”

Supplement

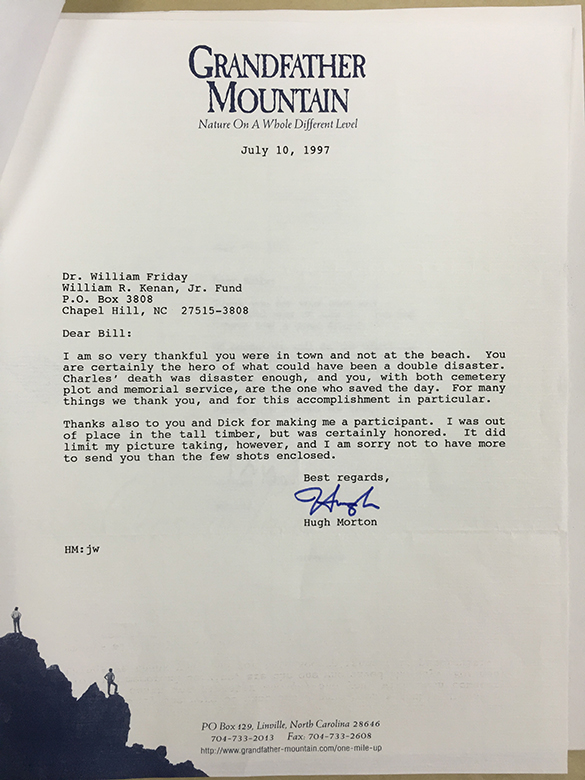

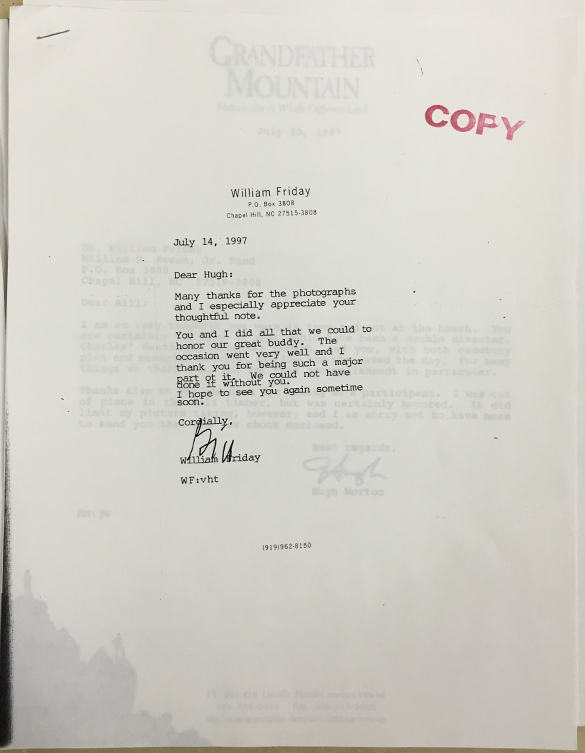

William C. Friday’s papers in the Southern Historical Collection contain the following letters between Friday and Hugh Morton, written soon after the Kuralt memorial service.

Epilog

On October 12, 2012 (University Day on the UNC campus), former UNC System President Dr. William Clyde Friday passed away. He, too, is at peace in the Old Chapel Hill Cemetery.

Correction: A caption to a photograph in the original version of the story stated that the unidentified person on the left of the group portrait with McGlohon and Kuralt was thought to be Reverend David Thompson. A reader’s comment identified the man as James G. Babb (7 July 2017).

Twenty-nine years ago the North Carolina coastal fishing and tourist industries faced a very real problem. As most often is the case, the Hugh Morton family stepped in to offer help. Morton collection volunteer and blog contributor Jack Hilliard looks back to January, 1988 and a unique gathering of loyal North Carolinians.

Twenty-nine years ago the North Carolina coastal fishing and tourist industries faced a very real problem. As most often is the case, the Hugh Morton family stepped in to offer help. Morton collection volunteer and blog contributor Jack Hilliard looks back to January, 1988 and a unique gathering of loyal North Carolinians.