Winter solstice is upon those of us in the Northern Hemisphere—and today’s simple post features a bright and cheery photograph on this day with the least amount of daylight for the year.

Category: Nature

Autumnal Equinox

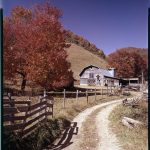

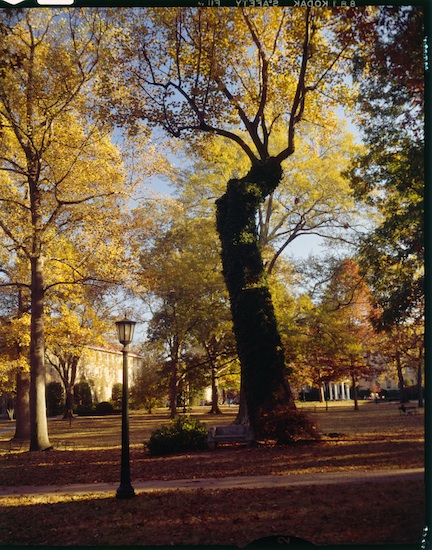

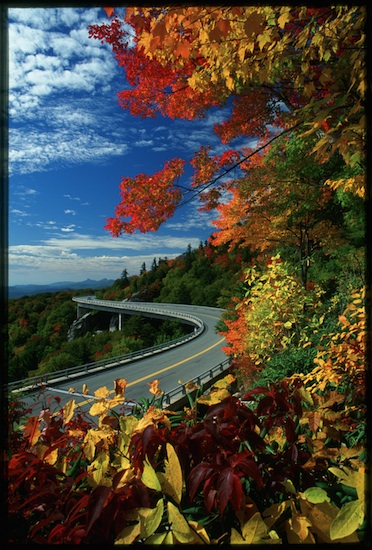

For our readers in the Northern Hemisphere, 2:04 a.m. marks the arrival of the autumnal equinox. As we revisit the new season, today’s post calls attention to some of Hugh Morton’s fall imagery—and provides an opportunity to try the “gallery “post format” to A View to Hugh’s new theme. Take a moment to explore other Hugh Morton autumn photographs. What are your favorite Morton fall scenes? How do you like the gallery post format? Please let us know!

New River Celebration Day

This coming Saturday, July 23rd 2011, will be New River Celebration Day at the New River State Park located near Laurel Springs in Ashe and Allegheny counties of North Carolina. What’s to celebrate? The river itself—the second oldest in the world—whose very nature survived a decade-long threat in the 1960s and 1970s.

The north and south forks of the New River wend their northerly way through northwestern North Carolina, meeting at their confluence to form the river’s main stem near the Virginia border. The region had been traditionally rural farmlands, but on March 11, 1963 the Appalachian Power Company (APCO), a subsidiary the American Electric Power Company (the largest electric utility in the country) received permission from the Federal Power Commission to conduct a two-year feasibility study for the potential generation of hydroelectric power on the upper New River.

As a result, on February 27, 1965 APCO filed an application for its “Blue Ridge Project”—a proposal for a non-federal hydroelectric power project to construct two dams on the New River in Grayson County, Virginia with the upper dam’s reservoir extending into North Carolina. The reservoirs would have a combined surface area of more than 19,000 acres. In 1966, however, the Department of interior proposed a larger project that would help flush pollution from the Kanawha River farther downstream, which eventually became known as the Modified Blue Ridge Project. That plan called for more than 38,000 to 42,000 surface acres, requiring the displacement of least 2,700 inhabitants in nearly 900 dwellings, plus numerous industries, churches, cemeteries, and other structures. And the power generated by the project was not for local resources but for distant customers.

In protest, citizens mounted a preservation effort that was soon joined by both the state and federal governments. The New River was not alone, however, in its plight. The nation was undergoing a revitalized environmentalism movement in the 1960s, and the condition of America’s rivers emerged as a major concern. On October 2, 1968, the United States Congress enacted the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which specified three river segments within the country that qualified for protection, including a 26.5-mile stretch of the New River from its confluence with Dog Creek to the Virginia border. With passage of this law, protected rivers could become part of a National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and the law offered two paths to achieve that protection.

The battle for the New River that followed was long and complex. What is interesting from the Hugh Morton perspective is that the early stages of the preservation effort were in play when Morton briefly campaigned as a candidate for governor the Democratic Party in late 1971 and early 1972. The headwaters of South Fork of the New River start from a spring at Blowing Rock in Watauga County, which as the crow flies is not far from Grandfather Mountain in Avery County. Research into Morton’s campaign might reveal if he ever spoke publicly about the subject.

The following few years saw the first statewide effort to fight for the New River, including the Committee for the New River in January 1975. The National Committee for the New River organized in 1974. (A NCNR map of the project illustrates the area that would have been effected by the project.) On May 26th, 1975 the North Carolina General Assembly designated that same 26.5 mile stretch of the New River included in the federal Wild and Scenic Rivers Act as a State Scenic River. Morton’s photograph above dates from May 1975, one of several he took that month. In 1976 the New River obtained its status as a National Scenic River, and the New River State Park opened in 1977.

You can read more about the efforts to protect the New River in

- Jay Wild’s History of the Management Plan for the South Fork of the New River in N.C., from the proceedings of the New River Symposium for 1984;

- Robert Seth Woodard Jr.’s Master thesis, The Appalachian Power Company Along the New River: The Defeat of the Blue Ridge Project in Historical Perspective, from Virginia Tech in 2006; and

- Thomas J. Schoenbaum’s The New River Controversy (New Edition, 2009)

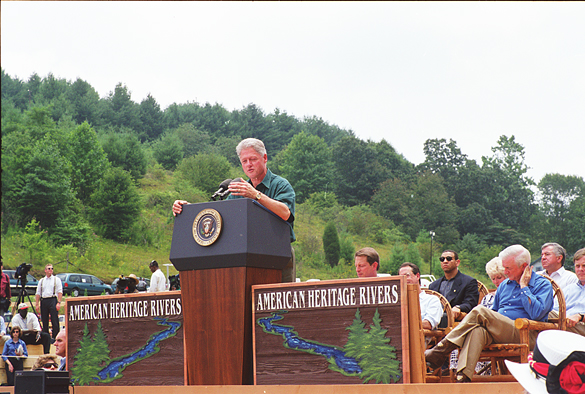

Morton and camera returned to the New River once again on July 30th, 1998 to photograph the ceremony designating the New River as an American Heritage River, an event attended by both President Bill Clinton and Vice President Al Gore. Clinton created the American Heritage Rivers Initiative by executive order on September 11, 1997.

'Ghost Cat' confirmed as ghost

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has confirmed that the Eastern Cougar (a.k.a. puma, mountain lion, catamount, red tiger, or “ghost cat”) is officially extinct — i.e., there have been no wild breeding populations of the species since, probably, the 1930s. Officials blame continuing, numerous mountain lion sightings in the eastern states on mistaken identity (either another animal entirely or a migrating Western Cougar), or on big cats escaped from captivity — though they may have trouble convincing many locals of that!

This sad news does provide an opportunity to highlight some of Hugh Morton’s striking photos of cougars in the wildlife habitats at Grandfather Mountain.

I’m not entirely sure when the first cougars came to Grandfather (circa late 1970s-early 1980s), or of the impetus for creating a habitat for them — perhaps some of the staff at Grandfather can shed light on that story? But I believe the image below to be one of those inaugural cougars, named Terra and Rajah, possibly upon arrival at the Mountain (judging from the ropes and the unhappy attitude). (Of these two, only Terra, shown in the photo at the top of this post, was an Eastern Cougar — Rajah was Western).

Mr. Morton was obviously taken with the animal’s extreme elegance and athleticism. He tried repeatedly to capture that perfect “cougar leap” image. I’m particularly fond of the shot below (taken in 1982 of the cougar named Judy).

Two cougars, Nakita and Aspen, currently live at Grandfather (though the website doesn’t say whether either or both of them are Eastern Cougars). At least, through captivity programs like Grandfather’s, we can take comfort that not all of these incredible animals will become “ghosts.”

Autumn Gallery

I’m headed up the mountain to Boone this weekend, hoping to catch what’s left of the colorful fall leaves. Here in Chapel Hill, they’re just getting started.

Hugh Morton, of course, had a marvelous eye for capturing fall displays; here for your enjoyment are a few showstoppers as well as some of my personal favorites.

A Man and his Mountain; Worth 1,000 Words concludes

It is with both sadness and relief that I announce the final installation of our Worth 1,000 Words essay project . . . sadness because I’ve so enjoyed each new essay and the varying perspectives our authors have brought to the Morton collection, and relief because, wow, this has been a lot of work! (I have a whole new respect for editors/publishers).

It is with both sadness and relief that I announce the final installation of our Worth 1,000 Words essay project . . . sadness because I’ve so enjoyed each new essay and the varying perspectives our authors have brought to the Morton collection, and relief because, wow, this has been a lot of work! (I have a whole new respect for editors/publishers).

But perhaps the sun hasn’t gone down for the last time on this project. All along, our intention with these essays has been to demonstrate the usefulness of Hugh Morton’s images beyond their obvious value as “pretty pictures.” As we stated in our original grant proposal to the North Carolina Humanities Council:

“Photographs are rich primary sources in themselves, full of historical detail, and as visual records, offer immediacy not available through text — a direct visual link to the past. Photography is also, of course, an art, one of which Hugh Morton was a master. The beautiful and communicative documents he created hold almost endless possibility for study, research, and exhibition. They also contain great potential for educational use at all levels, from grade school to graduate school.”

We heartily encourage researchers, journalists, students, teachers, history buffs, etc. to take up the mantle of our Worth 1,000 Words authors and continue to put Morton’s photos to work in the creation of new knowledge. We hope to find ways to encourage that in the future, e.g., through collaborations with media outlets and educators (here on UNC campus and/or in the public schools). We’d love to hear your ideas on ways to accomplish this.

And now to the final essay, entitled The Grandfather Backcountry: A Bridge Between the Past and Preservation, written by RANDY JOHNSON, the originator of Grandfather Mountain’s trail system. In this essay, Johnson provides his first-hand, behind-the-scenes perspective on the changing attitudes towards managing and providing public access to Grandfather’s backcountry. Combining Johnson’s piece with four of our other essays, by Drew Swanson, Anne Whisnant, Richard Starnes, and Alan Weakley, provides a fascinating, nuanced analysis (from multiple, sometimes conflicting perspectives) of the complex balancing act between profit and conservation at “Carolina’s Top Scenic Attraction.”

I’ll conclude with a final plug for our second (and last) Worth 1,000 Words event in Boone on Tuesday, August 10, which will feature both Johnson and Starnes. Come on out!

Tuesday, Aug. 10, 5:30 p.m.

Watauga County Library, Boone

Information: Evelyn Johnson, ejohnson@arlibrary.org, (828) 264-8784

- Randy Johnson: “The Grandfather Backcountry”

- Richard Starnes: “Selling North Carolina, One Image at a Time”

New essay, and upcoming events!

Today’s first order of business is to proclaim the availability of our newest Worth 1,000 Words essay, written by plant ecologist ALAN S. WEAKLEY and entitled Hugh Morton and North Carolina’s Native Plants (one of which can be seen at left). Weakley, Curator of the University of North Carolina Herbarium, a department of the North Carolina Botanical Garden, brings a unique perspective to our essay project as a scientist who worked closely with Hugh Morton on projects related to plant conservation at Grandfather Mountain. Please take a few minutes to read and respond to Weakley’s reflections.

Today’s first order of business is to proclaim the availability of our newest Worth 1,000 Words essay, written by plant ecologist ALAN S. WEAKLEY and entitled Hugh Morton and North Carolina’s Native Plants (one of which can be seen at left). Weakley, Curator of the University of North Carolina Herbarium, a department of the North Carolina Botanical Garden, brings a unique perspective to our essay project as a scientist who worked closely with Hugh Morton on projects related to plant conservation at Grandfather Mountain. Please take a few minutes to read and respond to Weakley’s reflections.

Secondly, and speaking of Worth 1,000 Words, we’d like to announce two upcoming Morton Collection events, FREE and open to the public, to be held in Wilmington on July 19 and Boone on August 10. Further details available on the Library News and Events blog here. If you’re in the area, we hope you’ll take this opportunity to come say hi to those of us who work on the collection, as well as to hear from and chat with some of our essay authors. See you there!

It's official…NC has a bunch of official symbols.

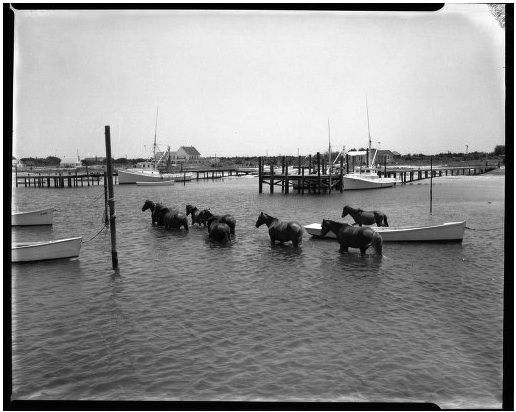

With a hat tip to our pals at North Carolina Miscellany, we inform you that North Carolina lawmakers have managed to find time in their busy schedules (state budget, anyone?) to name the Outer Banks’ wild mustangs as the official “state horse.” Hugh Morton was fond of photographing these charming ponies as they wandered through the harbor at Ocracoke.

From this AP article I learned the interesting tidbits that in addition to well-known symbols like the state dog (the Plott hound) and the state flower (dogwood), there is also a state insect (the honey bee) and a state BEVERAGE (milk).

So, I decided to try and determine how many of NC’s official state symbols Hugh Morton photographed. The answer: quite a few! I created the nice thumbnail gallery below to showcase some of the highlights. Hope you enjoy.

NOTE: If you’re a fan of all things North Carolina, you simply must check out the newly-launched website for materials published by the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center: DigitalNC.org.

The Mountain: before, during, and after Morton

As I hope you noted in my last post, the almost 71,000 Hugh Morton images from the Grandfather Mountain Series are now part of the collection’s online finding aid and are open for research. These images date from the late 1930s through the early 2000s, and thoroughly document Morton’s intimate, life-long connections to the Mountain.

In the latest essay in our Worth 1,000 Words series, scholar DREW A. SWANSON explores this relationship and also reminds us that the Mountain was there long, long before the man, and will exist long, long after. How did tourism and development affect the Mountain’s ecosystems before Morton inherited it? What impacts did his actions, in the areas of both development and conservation, have? What can we expect in its future as a state park?

Read Drew’s essay, entitled Grandfather Mountain: Commerce and Tourism in the Appalachian Environment, and let us know your thoughts about these issues.

Series 3 (Nature & Scenic) available!

Just a quick note to let you know that Series 3, and all the gorgeous, meditative splendor contained therein, is now available and included in the online finding aid for the Morton collection. (Note that the URL for the finding aid has changed, but the old link will redirect you to the new one). Note also that this is the first series to include 35mm slides in its inventory (we’re working on adding the slides for Series 1 & 2 retrospectively). Enjoy!