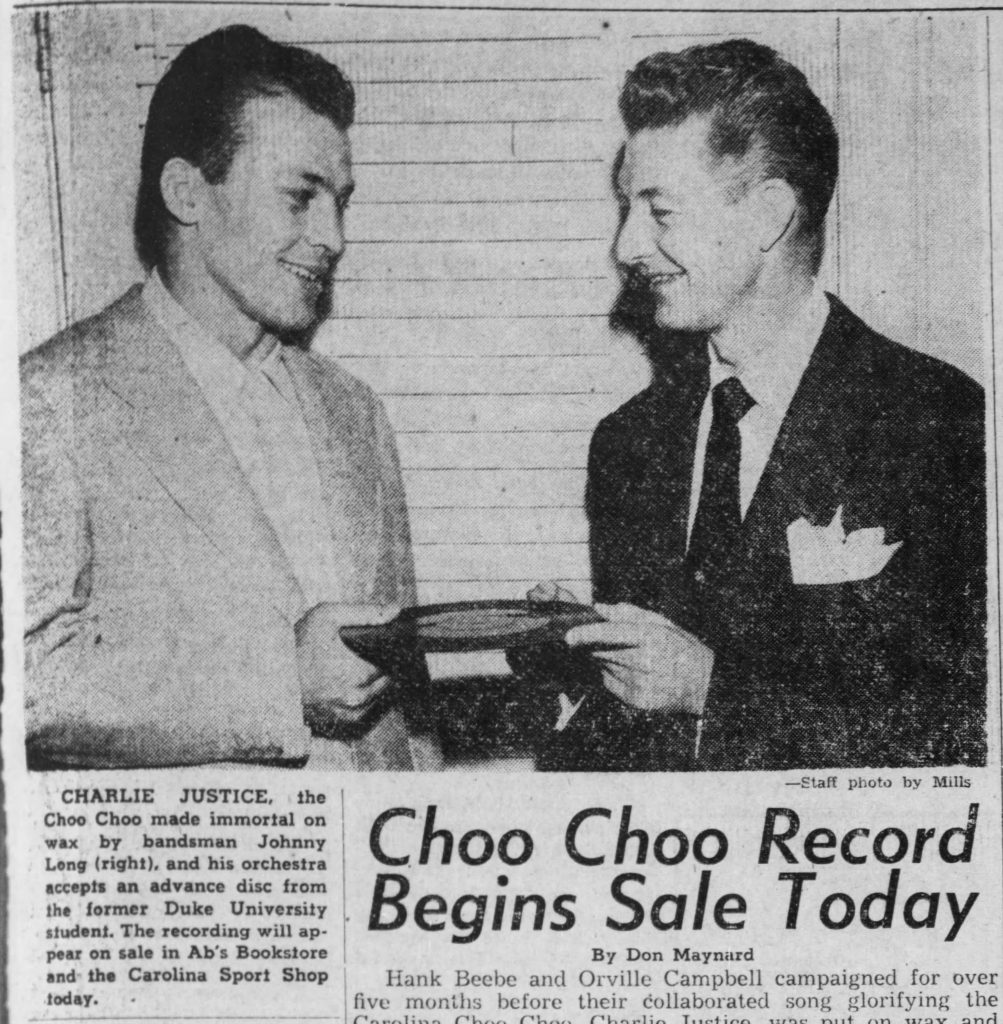

Today, October 27th, UNC head football coach Larry Fedora leads his 2018 Tar Heels into historic Scott Stadium for a continuation of “the South’s Oldest Rivalry.” This game between the University of North Carolina and the University of Virginia marks the 123rd meeting between the two old rivals. Over the years, since the first meeting between the two in 1892, Carolina has won sixty-four times while UVA has won fifty-four; four games ended in a tie. Of the fifty times Carolina has played UVA on the road, the game in 1948 not only provided Carolina with a highly significant win, it also provided an interesting sidebar story. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard takes a look back at the game in Scott Stadium on November 27, 1948 between the Tar Heels and the Cavaliers.

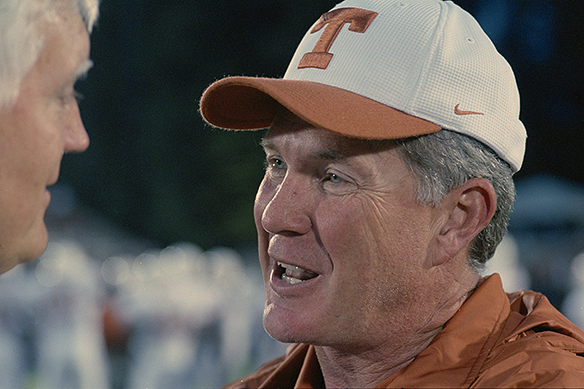

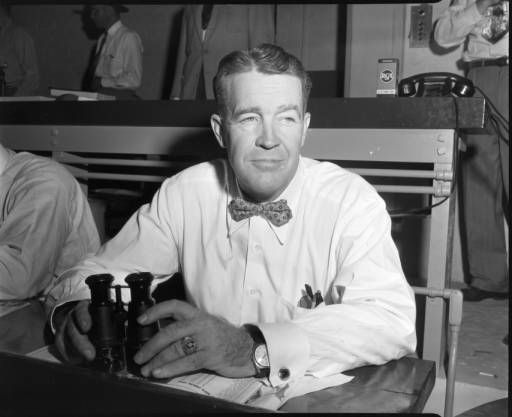

Arguably the best UNC football team was the 1948 squad that finished the season undefeated and ranked third in the Associated Press poll. The ’48 Tar Heels started off the season at home with a historic win over the University of Texas, 34 to 7. (Many old-time Tar Heels still like to talk about this game.)

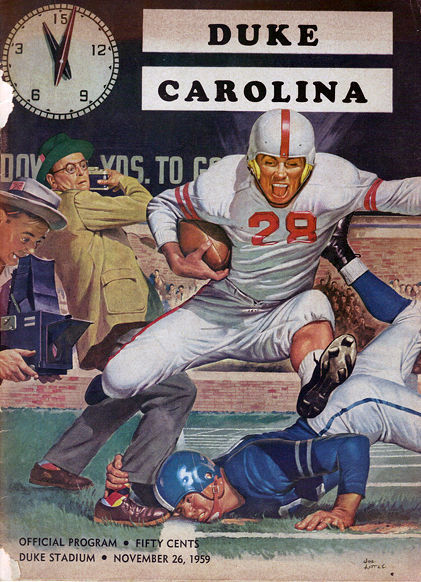

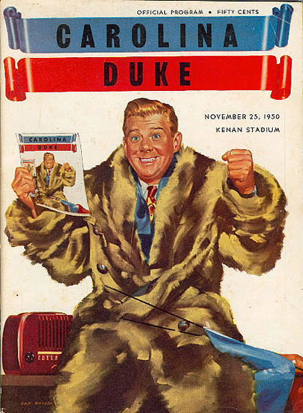

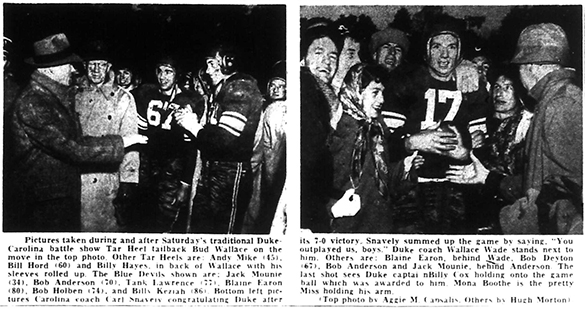

The weekend following the Texas win, Charlie Justice had his best day as a Tar Heel down in Georgia with a win over the Bulldogs. Then came wins over Wake Forest, NC State, LSU, and Tennessee. A tie with William & Mary on November 6th was the only blemish on the ‘48 schedule. Following wins over Maryland and Duke, it was time to close out the historic season—a season that had seen Carolina ranked number one for the first and only time.

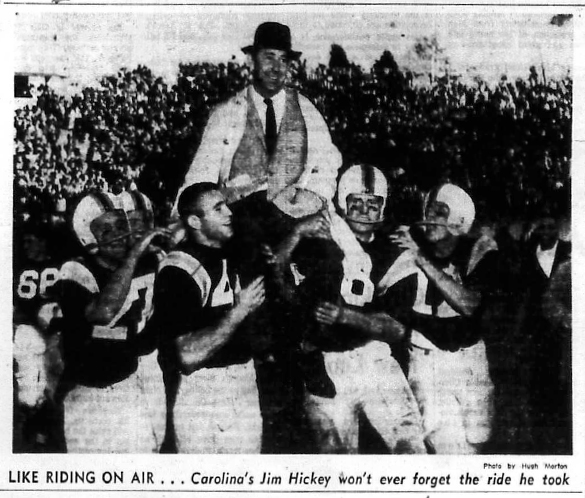

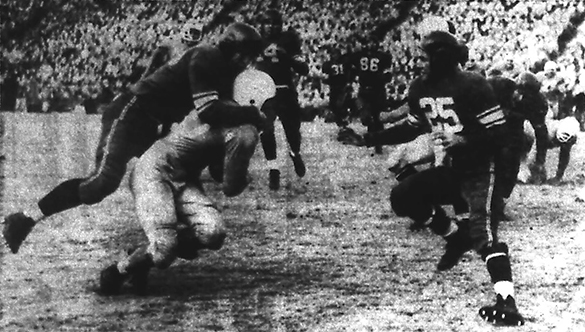

With bowl talk in the air, Head Coach Carl Snavely took his team into Scott Stadium for that finale. An overflow crowd of 26,000+ turned out on November 27, 1948, a day that could have very easily been called “Charlie Justice Day.” Here’s why:

- He got off runs of twenty-two and eight yards in the initial Carolina touchdown drive.

- He passed thirty-nine yards to receiver Art Weiner for the second Tar Heel score.

- He cut off left guard on a delayed spinner and outran the field to cross the Virginia goal eighty yards away.

- He passed thirty-one yards to end Bob Cox for Carolina’s fourth touchdown.

- He returned a UVA punt, in a straight line, fifty yards for Carolina’s final touchdown of the day.

In summary: Justice carried the ball fifteen times for a net total of 159 yards—that’s almost 11 yards per carry. He completed four of seven passes for 87 yards. He returned two punts for sixty-six yards. He punted five times for a 40.8 yards per punt average. And oh yes, he intercepted a Virginia pass, had a 49-yard touchdown pass called back as well as a 21-yard run. Needless to say, Carolina won the game 34 to 12 and went on to play in the 1949 Sugar Bowl.

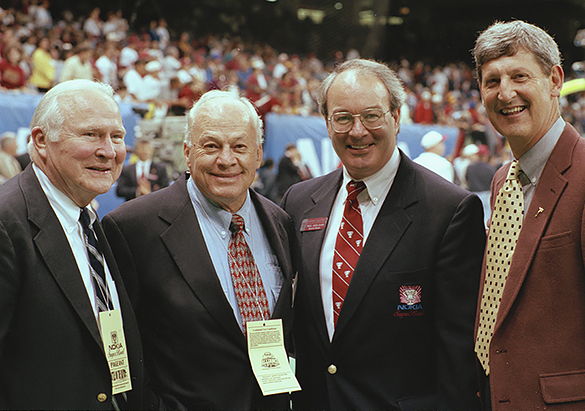

Among those 26,000+ fans in Scott Stadium that afternoon was an eleventh grade student at Woodberry Forest, a prep school in Madison, Virginia. His name, Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. from Charlotte, North Carolina. Spangler, along with several of his school buddies, had made the trip over to Charlottesville for the game. (Clemmie Dixon Spangler, Jr. would become known as C.D. Spangler, Jr. and would lead the University of North Carolina system from 1986 until 1997.)

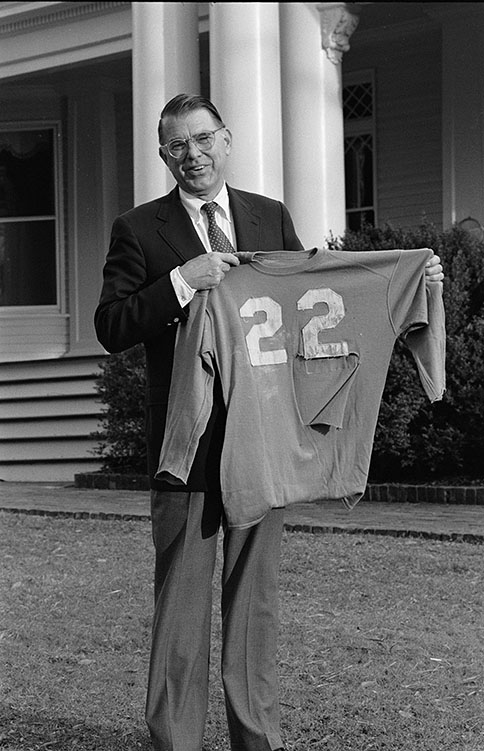

On one of those great Charlie Justice plays mentioned above, Justice’s #22 jersey was torn. He came over to the Carolina sideline where equipment manager, “Sarge” Keller, quickly got out a new one . . . tossing the torn one over behind the bench into an equipment trunk. In a 1996 interview with A.J Carr of Raleigh’s News & Observer, Spangler described the 1948 Charlottesville scene:

“Charlie was a hero of mine. It was one of his greatest college games. On one play, a linebacker grabbed him, but he twisted away as he often did, ran another 10-15 yards and his jersey was torn.”

“He came over, the trainer helped him put on another and they put the torn one in the trunk. I said: ‘That old jersey would be nice to have.’”

After the game, Spangler got the attention of a Carolina cheerleader and explained that he wanted the Justice jersey. He then offered the cheerleader ten dollars to go and get the jersey out of the trunk. The deal was completed and as Spangler walked out of the stadium, some Carolina fans offered him one hundred dollars. Spangler said, “No deal.”

He displayed the jersey on the wall while in high school and after graduation he kept it in a “safe place.”

“I wouldn’t take anything for it,” Spangler continued. “It’s a piece of history that meant something to me.”

“My mother offered to wash it and sew it. But I said we would not wash it, that we’d keep the lime marks and grass stains and leave it torn.”

“(Charlie Justice) is very symbolic of someone who did well, was a hero and he lived a really good life. He lived up to all expectations and has been a fine representative for North Carolina,” Spangler added as he closed the interview.

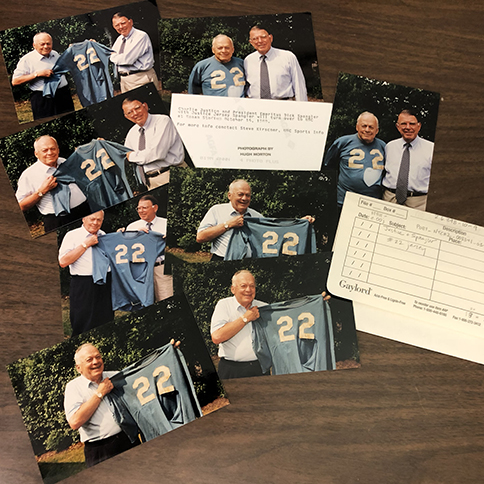

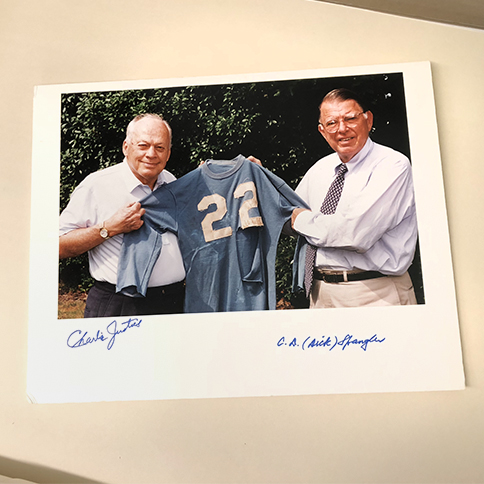

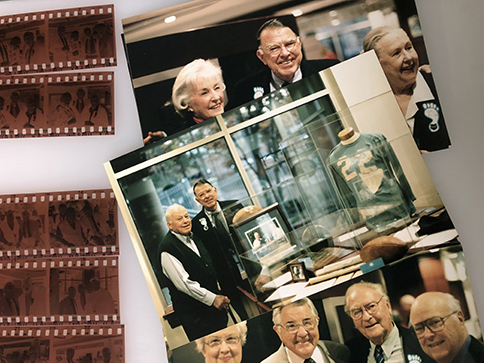

Spangler kept the prized memento for more than fifty years. Then, on November 18, 1989, during halftime of the Carolina–Duke game, he presented the jersey to then UNC Athletic Director Dick Baddour. It is now on display in the Charlie Justice Hall of Honor at the Kenan Football Center.

Morton also used the images in his slides shows, saying: “…the only university president who freely admits to bribery and stealing.”

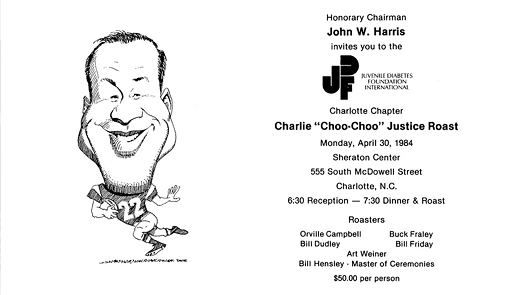

On April 30, 1984, the Charlotte chapter of the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation staged a Charlie Justice Celebrity Roast and one of the roasters was Justice’s dear friend, teammate, and business partner Art Weiner. One of Weiner’s roast stories went something like this:

We knew that Charlie was competing with SMU’s great All America Doak Walker for the 1948 Heisman Memorial Trophy. When we read in the papers that Walker had a jersey torn up during one his games, we decided, in the huddle, to tear up one of Charlie’s . . . just to make things look equal. But on November 27, 1948, the tear was for real and C.D. Spangler, Jr. got a “Priceless Gem for Only 10 Bucks.”