On this day . . . actually night . . . sixty-five years ago, a sporting event played out on Soldier Field in Chicago that would have a tremendous impact on North Carolina sports history. It was August 11, 1950 when the Chicago College All-Star Game game between the best college players of the 1949 season met the two-time World Champion Philadelphia Eagles. On this special anniversary, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back at a football game of epic portions.

Hugh Morton didn’t attend the 17th annual Chicago College All-Star Game, but he was always acutely aware of its place in North Carolina sports history and in the life of one of his closest friends. Morton often included a wire service photograph in his slide shows from that historic night—a night that almost wasn’t historic at all.

It was July 17th, 1950 and UNC’s great all-America football star Charlie Justice was seated behind his desk in the Medical Foundation Building on Pittsboro Street in Chapel Hill. It’s was the first July since 1938 that he wasn’t preparing for the upcoming football season. Soon after taking the Medical Foundation job, the United States Department of State invited Justice to travel to Germany with coaches Jim Tatum of Maryland, Wally Butts of Georgia, and Frank Leahy of Notre Dame to hold football coaching clinics for the armed forces stationed there. In order the make the trip, Justice had to turn down an invitation from Arch Ward (sports editor of the Chicago Tribune and founder of the Chicago College All-Star Game) to play in that year’s game.

The overseas trip never happened because of events that began on June 25th, 1950— events that would later become known as the Korean War. So Justice picked up the phone and called Arch Ward. He asked Ward if the earlier invitation to play in the All-Star game still stands, saying “I’d like to play.”

Ward explained that he had already selected fifty top-notch players for the contest. He also pointed out that the rules of the game allowed only four future NFL players from each NFL team, and that he already had four Washington Redskins’ players. Charlie quickly pointed out that, although he was drafted by Washington, he had no plans to play for them. Ward finally said, “OK, Charlie, if you’re sure you aren’t planning to play for Washington, and you want to be the 51st player on a 50-man team, come on out. We’ll let you return punts and kickoffs.”

“I’ve given the Medical Foundation my word and I’ll be right here come football season,” Charlie told Ward. Justice was on the next flight out. The banner headline in the Chicago Tribune on July 18th read: “NORTH CAROLINA’S JUSTICE JOINS ALL-STARS.”

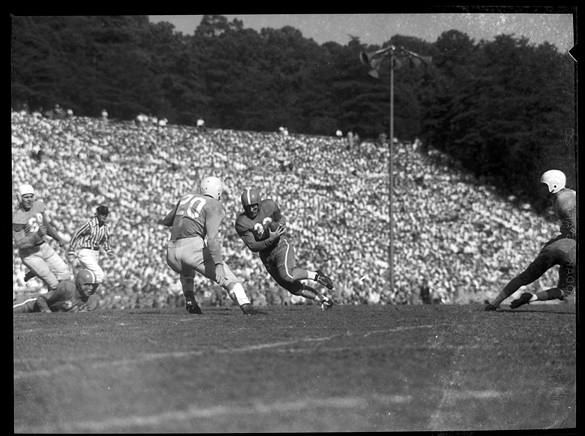

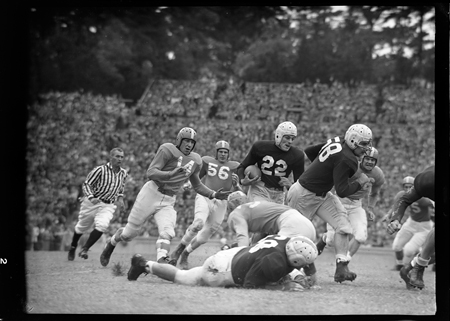

A crowd of 90,000 was expected on a clear, cool 60-degree summer evening at Soldier Field. The two-time World Champion Philadelphia Eagles won veteran NFL referee Emil Heintz’s opening coin-toss, but head coach Earl “Greasy” Neale’s team couldn’t move the ball, thanks to the defensive efforts of All-Stars Clayton Tonnemaker, Leo Nomellini, Don Campora, and Leon Hart. Justice went in on the punt return team, but the Eagle punt was returned by the All-Stars’ Hillary Chollet to the Stars 46-yard line. As Charlie started off the field, the All-Star head coach, Eddie Anderson, motioned for him to stay on the field. Anderson said, “run this first series, Charlie, so we can get an idea of what kind of defense the Eagles will be using . . . it’ll give us an idea of what offense we should use.”

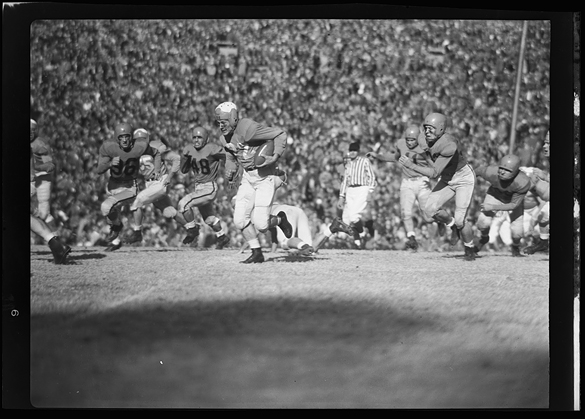

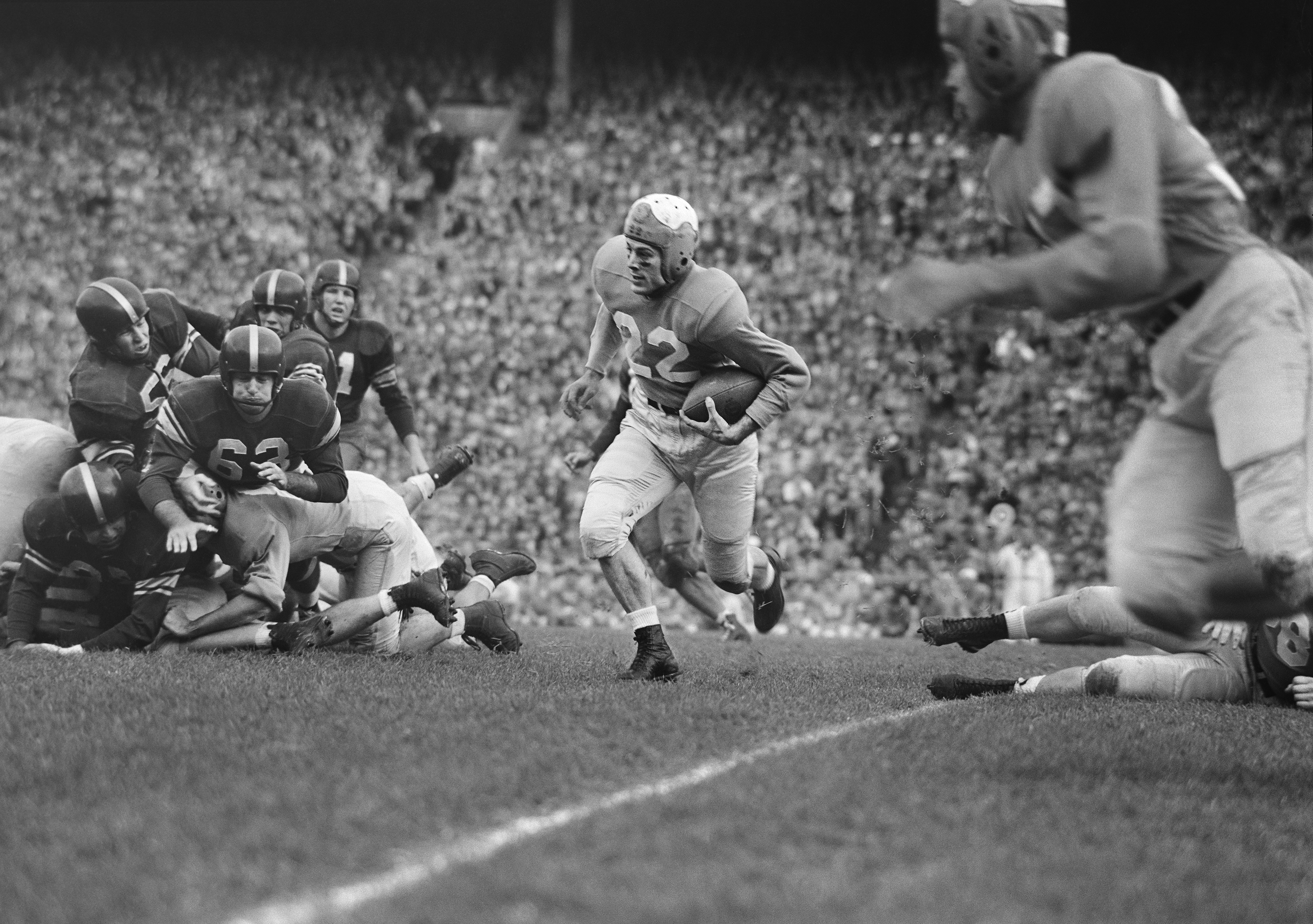

On the first play from scrimmage, quarterback Eddie LeBaron pitched out to Justice around the right side and Charlie was off on a thirty-one yard gain. Three plays later it was Justice again, this time for twelve more yards. On the next play All-Star Ralph Pasquariello from Villanova took it over the goal line, and the All-Stars led 7-0. Needless to say, Justice stayed in the game.

On the first play of the second quarter, Justice raced down the sideline for forty-seven more yards. This All-Star drive stalled, but when they got the ball back on an Eagles’ fumble by Clyde Scott, recovered by Hall Haynes (future Justice Redskins teammate) on the Eagle 40, LeBaron dropped back to pass, eluded three pass rushers and finally rifled a pass from his own 40 to Justice who went the distance for a score. The play actually covered a total of 60 yards and Winfrid Smith, writer for the Chicago Tribune, described the play as “the greatest pass play in the history of these games.” Football historian Raymond Schmidt in his 2001 book, Football Stars of Summer said “the All-Stars led the Eagles 14-to-0 at the half and the football world was in shock.”

In the third quarter the Eagles finally scored, but the All-Stars came right back in the fourth with Justice leading the way—this time his 28-yard run plus a 35-yard pass from LeBaron to UNC All-America Art Weiner pass set up Gordon Soltau’s 17-yard field goal that made the final score 17-7. When the dust settled, the All-Stars had gained 221 yards on the ground—an All-Star record that still stands—and Charlie Justice had carried the ball 9 times gaining 133 yards. That’s 14.8 yards per carry. He had runs of 31, 12, 47, and 28 yards. His 133-yard total was 48 yards more than the entire Eagle team gained on the ground. Justice also completed a pass to his UNC teammate Art Weiner for 15 yards and he caught a 35 yard TD pass from LeBaron.

Back in North Carolina, thousands of Tar Heels listened to the game on radio—two of those folks were my dad and me. We sat in our living room in Asheboro listening to WGBG in Greensboro. A summer thundershower blew through the Triangle area and caused the Durham Bulls game with the Raleigh Caps to be postponed, thus giving those fans an opportunity to listen as well.

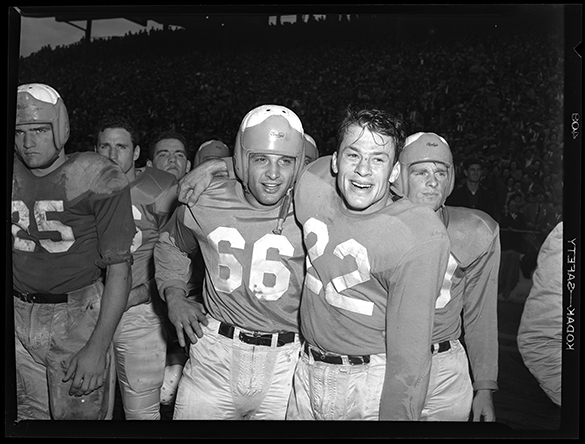

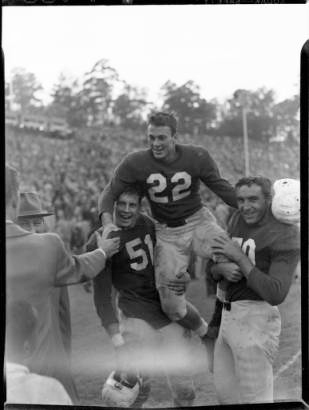

On Saturday August 12th, Charlie heard on the radio that he had been selected the game’s Most Valuable Player and would received the MVP trophy at halftime of the 1951 game. UNC Coach Carl Snavely would make the presentation. Newsmen and broadcasters covering the game selected the MVP. Justice was a 2-to-1 choice over runner-up LeBaron. Six All-Star linemen got votes. Justice thought LeBaron should have gotten the MVP award. Said Charlie, “Eddie deserves it. He’s a great little quarterback and a fine passer.”

“Never since the MVP voting began in 1938 has the voting been so concentrated,” said Winfrid Smith the next day in the Chicago Sunday Tribune.

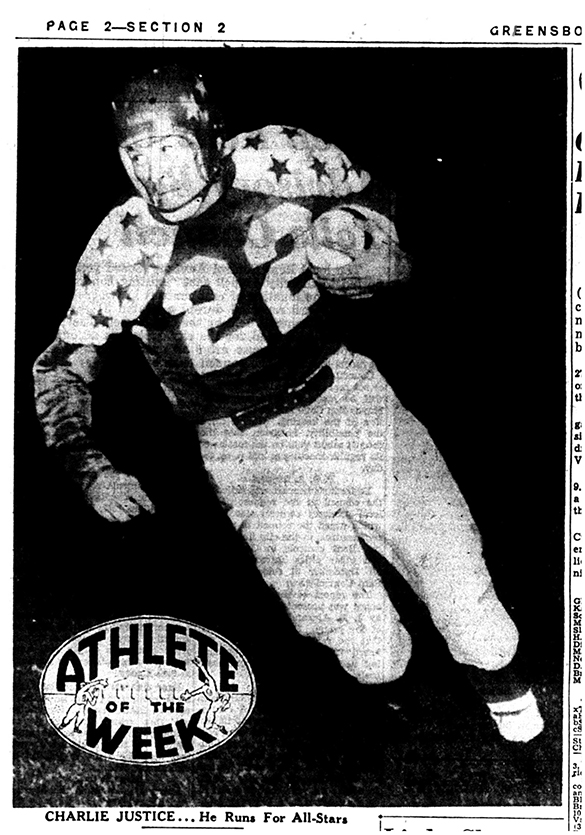

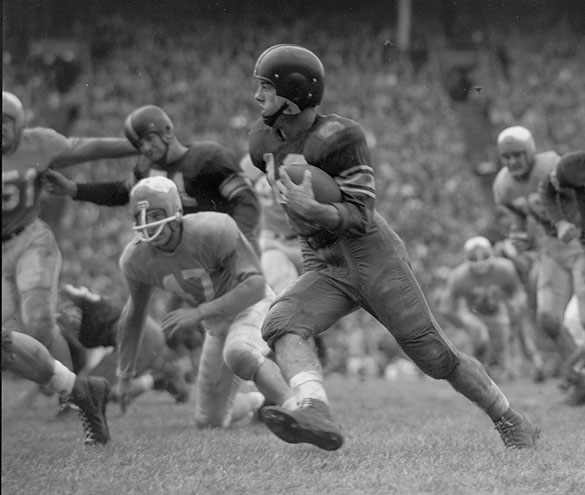

A game-action photograph of Justice accompanied a Smith Barrier column on Tuesday, August 15th story naming him the 152nd Greensboro Daily News “Athlete of the Week.” It was the 6th time Justice had received that honor. It was this photograph that Morton copied and included in his slide shows over the years. Though no credit appears in the copy slide nor the Greensboro Daily News, the Sunday, August 13th issue of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution credits Acme Photos. (Editor’s note: according to the Library of Congress, Corbis purchased the Acme photographic archives. I searched the Corbis website but this image did not turn up.)

On August 17, 1951, Charlie Justice received the 1950 MVP All-Star trophy, presented by UNC Head Football Coach Carl Snavely. That presentation was seen live across North Carolina via the Dumont TV network, WBTV in Charlotte, and WFMY-TV in Greensboro. The TV Network linked 46 stations and the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS) Radio Network had 528 stations.

Said Snavely of his Tar Heel All-American, “You saw Charlie do in last year’s All-Star game what we saw Charlie do many times . . . what we came to expect Charlie to do every time he got on the football field. I doubt if there has been a finer all-around player in football than Charlie.” Charlie’s response was “It’s the highest honor that can come to a football player. . . . I accept the trophy for the entire 50-man All-Star squad. . . . They all should be getting one.”

In a Charlotte Observer column on February 21, 1957 written by Justice, he said, “…I would say without hesitation that the high spot of my career came in the 1950 All-Star game in Chicago.”

In July, 2004, Hugh Morton was the point man for the Charlie Justice statue that now stands just outside Kenan Stadium. In a note to Glenn Corley, the architect who designed the statue-area surroundings, Morton said, one of the Justice informational plaques planned for the area should include “what I feel was one of Charlie’s most exciting accomplishments: MVP for the College All-Star game.” Morton then sent me a note asking, “Can you fill me in on the info of the College All-Stars versus the pros?”

I was honored to fill Morton’s request and today, if you stand in front of the statue, the informational plaque on the far right tells of Justice’s MVP performance of August 11, 1950, sixty-five years ago tonight.

Category: Football

A Tar Heel tradition in blue & white

A Chapel Hill “Rite of Spring” will be carried out in Charlotte this year. Head Football Coach Larry Fedora will take his Tar Heels to the Queen City for the 70th anniversary Blue-White football game because the renovations being carried out at Kenan Stadium will not be completed in time for the game on Saturday, April 11, 2015. [4/11/15 Update: according to GoHeels.com, the team is calling this a “open spring football scrimmage,” adding “Carolina will not have a traditional Spring Game in Chapel Hill due to ongoing repairs to the Kenan Stadium playing surface.”]

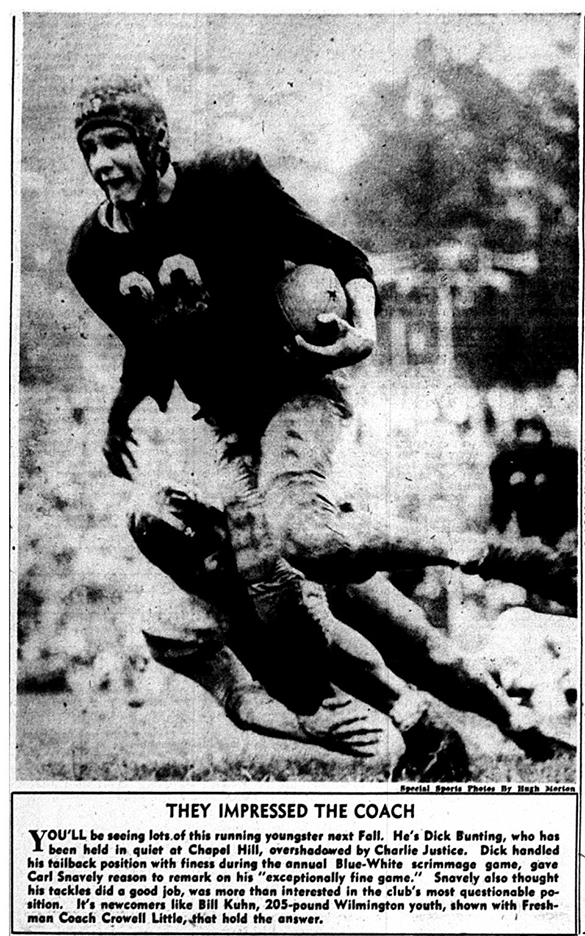

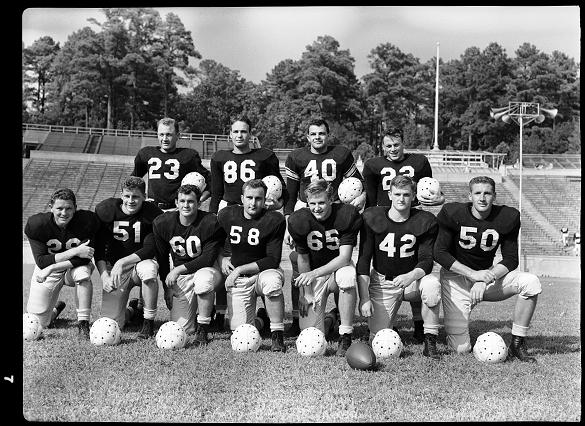

The annual spring game goes all the way back to 1946 when then Head Coach Carl Snavely put his post World War II squad on display in Kenan Stadium. Hugh Morton, as you might have suspected, photographed some of these early contests. Unlike his negatives for UNC basketball’s version of the Blue-White game, which are identified, Morton did not label his football negatives for the spring outing. I turned to newspapers looking for articles and images, then looked through hundreds of unlabeled negatives; Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looked over news reports from the Daily Tar Heel, Greensboro Daily News, Wilmington Morning Star, and Charlotte News. The result? Jack’s piece for today’s post on the beginnings of a Tar Heel tradition . . . and a few more identified negatives than we had beforehand.

Thirteen days after UNC Head Football Coach Carl Snavely got his Valentine wish that Charlie Justice would “come out for the team,” a practice game was held in Kenan Stadium between the Tar Heels and the Guilford College Quakers coached by Doc Newton. About a thousand students showed up despite the cold, damp, windy weather. The students were surprised when Snavely sent his team onto the field and Justice remained on the sideline. The modified format game gave Guilford the ball first and they did well. When the Tar Heels took over the ball, it was at their own 34-yard-line. On the sideline, Snavely snapped, “Justice, try tailback for a while.” As Justice ran onto the field, the crowd came to its feet. The Quaker defense dug in. Justice was on trial.

As everybody suspected, Justice got the snap. He started out to his right, then peeled off between the tackle and end, and was into the secondary. Two Quaker linebackers missed tackles, and now Justice was in position to size up the safety man. He ran directly at this last line of resistance, applied a head and shoulder fake and breezed past, then angled into the end zone. There was stunned silence in Kenan Stadium as the onlookers tried to figure out what they had just seen. Then a spontaneous cheer went up.

The United Press story in the Greensboro Daily News issue of February 28, 1946 said: “If his initial showing is any indication, Charlie Justice, the University of North Carolina’s new football star, can expect to cause opponents plenty of unrest.”

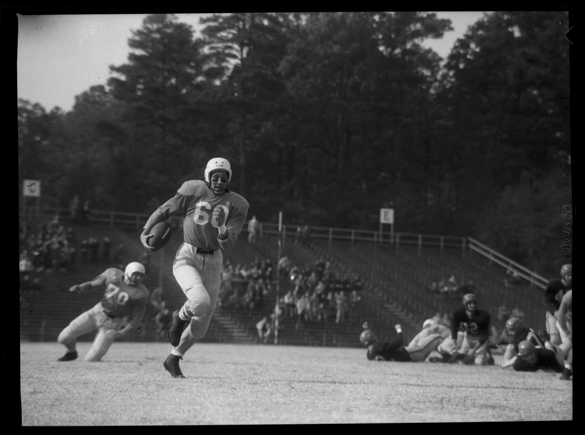

As the 1946 spring practice came to a close, Coach Snavely along with the University Monogram Club staged something new. They divided the 70-man football squad into two teams for a special game in Kenan Stadium. It was billed as the first annual Blue-White game and was played on May 4, 1946 before 2,000 top-coated fans. Charlie Justice, who had gotten a lot of ink in the papers by now, was assigned to the White team.

The Blue team got the ball first but after about two minutes, they punted. On the first play from scrimmage, with the ball at the White 35, Justice took off around right end. To quote Yogi Berra, “it was déjà vu all over again.” This time the play covered 65 yards. The White team went on to win that first Blue-White game 33 to 0. The ’46 Tar Heels finished the season 8-1-1 and it was “Happy Times are Here Again” in Chapel Hill.

Word of the successful 1946 Blue-White game spread quickly and when the 1947 game rolled around, 7,000 fans turned out on a warm April Saturday. The ’47 game had all appearances of a regular game as two squads of 41 players each met in Kenan on April 26, 1947. Unlike the ’46 game, this game was a tight, hard-fought contest with the White team winning in the end over the Justice-led Blue team 7 to 6. Place-kicker Bob Cox made the difference. It would be Charlie Justice’s only Blue-White loss. Although the 1947 Tar Heels lost 2 games—one to Texas and one to Wake Forest—and they chose not to accept a bowl invitation. Coach Snavely often said he thought his ’47 Carolina team was his best.

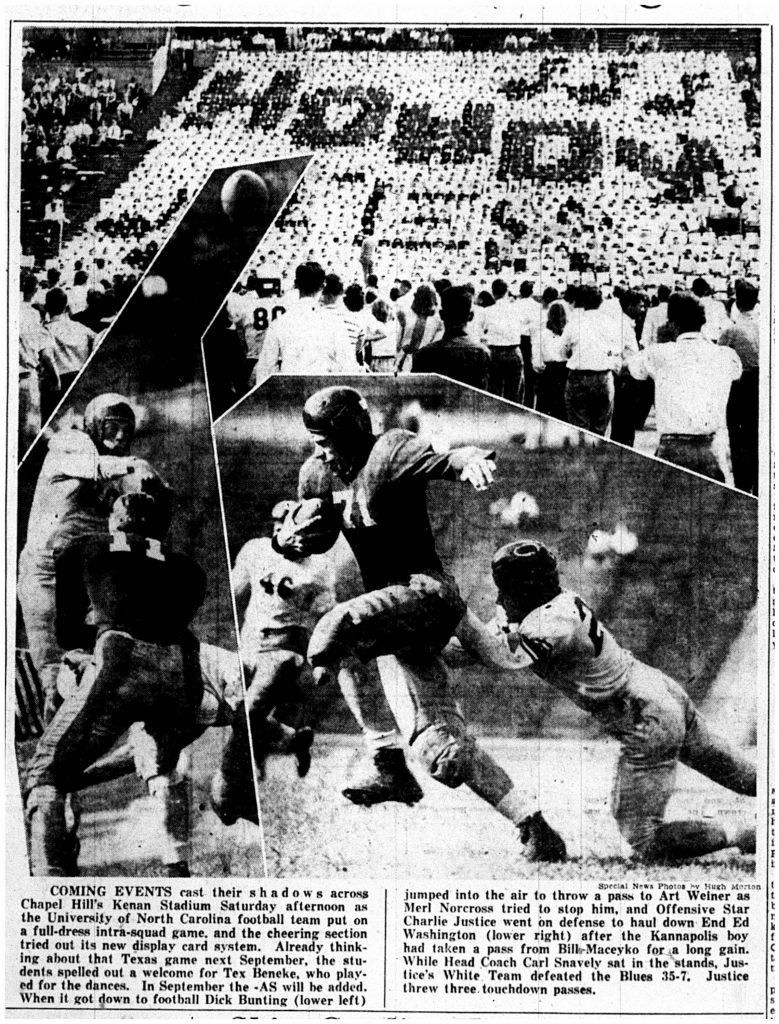

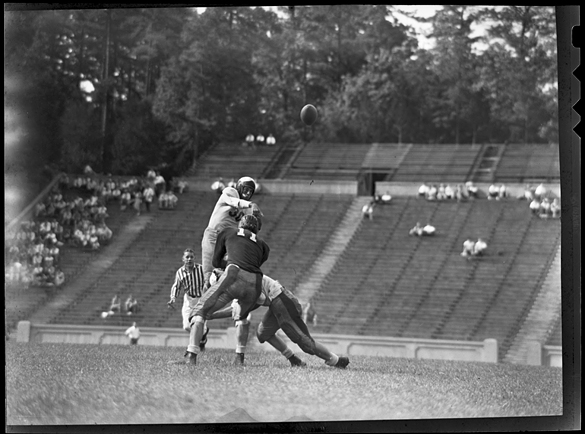

By April 29, 1948, Carolina had completed all of its spring practice and work was under way by the Monogram Club for the third annual Blue-White game to be staged in Kenan on May 1st. Once again, Coach Carl Snavely divided his troops into two teams: the White team to be coached by Jim Gill, and the Blue team to be led by Max Reed. This time 10,000 sun-baked fans came out to see what the ’48 Tar Heels had to offer. As it turned out, they had plenty to offer. The White team with Justice and Art Weiner at the controls scored three touchdowns in the first half and added two more in the second, making the final 35 to 7. The third annual Blue-White game introduced a new Carolina tradition. Head Cheerleader Norman Sper presented for the first time on the East Coast the 2,000-student Carolina Card section. They performed eight different stunts, to the delight of the crowd. The 1948 Tar Heels were undefeated: a tie with William & Mary was the only blemish on an otherwise perfect season. The stage was set for the final season of the “Charlie Justice Era,” but it would not be Charlie’s final Blue-White game.

Here’s a PDF of the above news clip: CharlotteNews_19480503_p6B. Only one negative from this trio has been located thus far:

The format for the fourth Blue-White game in 1949 was slightly different from years past. Upperclassmen like Justice and Weiner made up the Blue team, while freshman made up the White team. A Kenan Stadium crowd of 12,000 sat through a first-quarter rain and saw Justice run for one touchdown and pass for two as the “old guys” beat the “rookies,” 21 to 6.

Special guests for this game were 5,000 high school students from across the state.

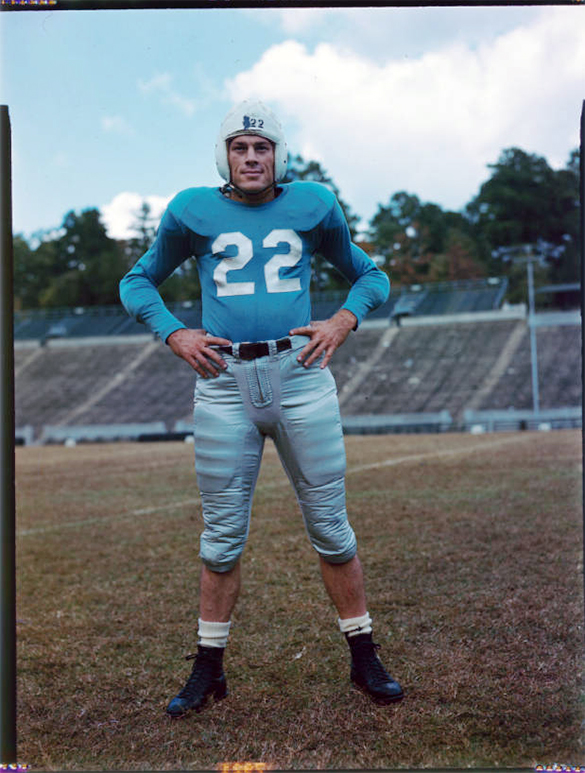

Photographer Hugh Morton attended several Blue-White games over the years. His classic shot of Justice at the ’49 game (seen at the top of of this article) is a scene many had come to expect in their Sunday papers.

Here’s a PDF of the article and two photographs as they appeared in theMay 2nd edition of The Charlotte News: CharlotteNews_19490502_p4B

The 1949 Tar Heels lost three games during the season but still won the Southern Conference title and played in the 1950 Cotton Bowl on New Year’s Day.

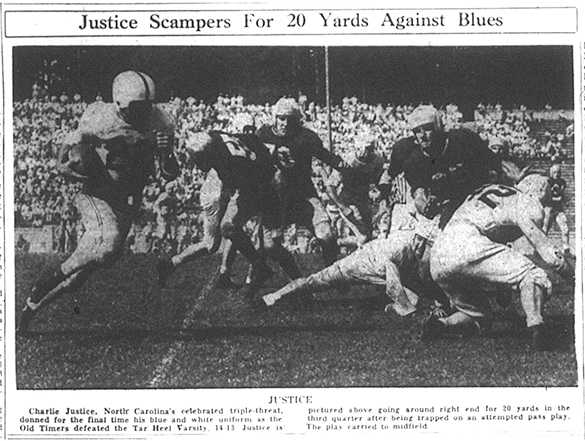

May 6, 1950, UNC’s Monogram Club staged its fifth Blue-White with yet another format change. This time it was the “Old Grads,” vs. the 1950 varsity. As you might guess, Charlie Justice and Art Weiner were co-captains for the “Grads.” 19,000 fans endured 90 degree temperatures and saw Justice steal the show once again, carrying the ball 12 times.

The “Choo Choo” had five punts for an average of 51 yards-per-kick. The star for the varsity was sophomore tailback Ernie Liberati who just happened to be the subject of Hugh Morton’s photo in the Greensboro Daily News issue of May 7, 1950. Morton, in an impromptu interview with Daily News Sports Director Smith Barrier said, “Fish are beginning to bite around Wilmington.” With all the big guns gone, the 1950 Tar Heels struggled, posting a 3-5-2 record for the season.

On April 28, 1951, the UNC Monogram Club staged the sixth Blue-White game in perfect football weather before 11,500 fans in Kenan Stadium. The varsity (White) vs. freshmen (Blue) format was in place once again, and as before the varsity proved to be too much for the “rookies.” Coach George Radman’s White team won 32 to 21. Radman’s assistant coach was Charlie Justice, participating in his sixth Blue-White game. Justice was on Snavely’s staff during the 1951 season before returning to his duties with the Washington Redskins for his second Redskins season in 1952. The ’51 Tar Heels finished the season with a 2 and 8 record. Snavely would have only more season with the Tar Heels.

The Blue-White games just kept on coming and in the1962 game, the Monogram Club brought back the 1950 format with the Varsity (Blue) and Alumni (White). At age 37, Charlie Justice participated in his seventh and final Blue-White game. On April 7, 1962, Justice was used as the Alumni punter and got off punts of 35, 40, 39, 37, and 19 yards. The headline in the Greensboro paper on April 8, 1962 read, “Justice Booms Punts Again,” and the headline on page 219 in the 1963 UNC Yearbook, “ Yackety Yack,” read “Choo-Choo Returns for Alumni Game.”

So, when UNC Head Football Coach Larry Fedora’s 2015 Tar Heels take the field at Rocky River High School in Charlotte at 1 pm on April 11 for the 70th anniversary Blue-White spring game, I choose to believe that Justice, Weiner, Snavely and Morton will be together again, watching a Tar Heel Tradition in Blue and White.

From the wing to the T . . . (shirt, that is)

Happy New Year from “A View to Hugh.” On the Heels of last week’s post that included mention of SMU standout running back Doak Waker, Jack Hilliard recounts some additional Justice–Walker memories from 1950. For some perspective, I added the excerpts from The State, and some tidbits found while looking for any use of the photographs.

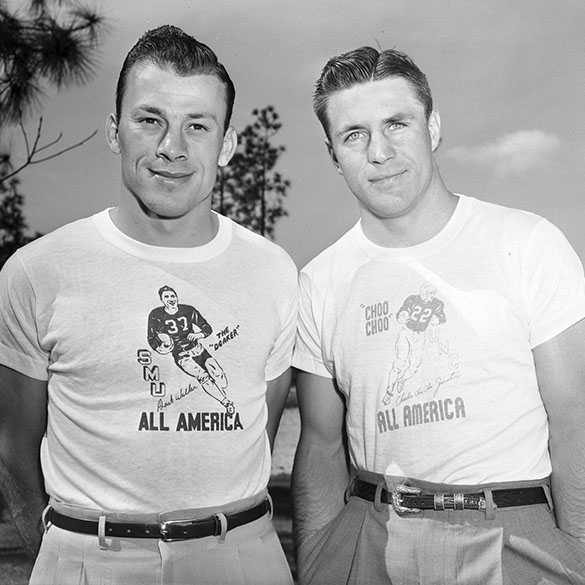

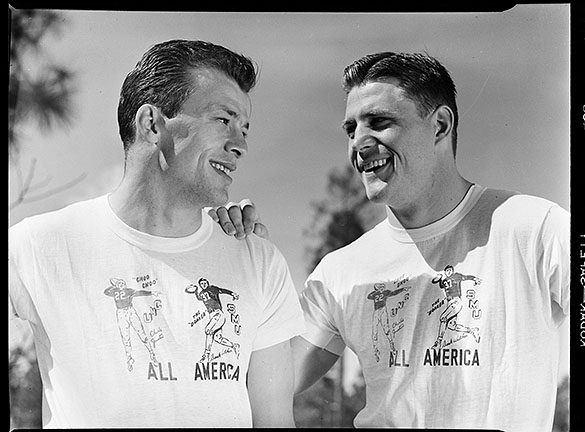

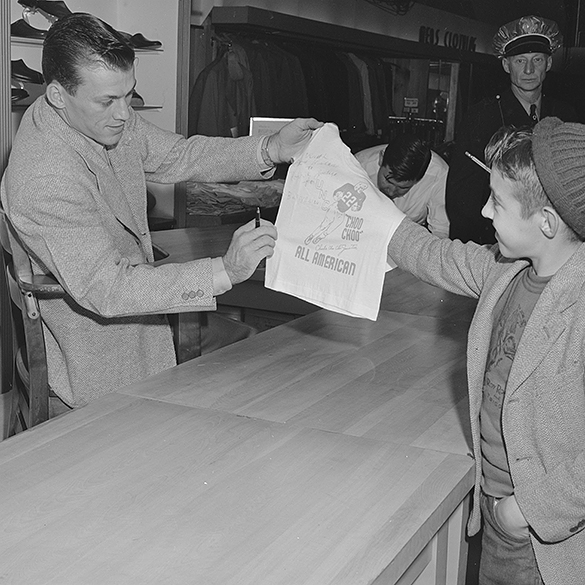

When UNC played Wake Forest on October 15, 1949 my dad and I were there. We arrived in Chapel Hill about 10 o’clock on that Saturday morning and visited on Franklin Street as we always liked to do. We stopped by The Varsity Shop at 149 East Franklin. In those days as I recall, they offered three different UNC T-shirts: one with the University logo, one that said UNC Class of 19??, and one with a Charlie Justice image that included Art Weiner, Walt Pupa, and Hosea Rodgers. The shirts were white with Carolina blue lettering, a major contrast to the hundreds of designs today at Johnny T-shirt, Chapel Hill Sportswear, or the Shrunken Head, among others on today’s Franklin Street. As I stood looking at the Justice shirt, my dad said “I’ll talk to Santa about one of those.” He must have, because on Christmas morning I got one.

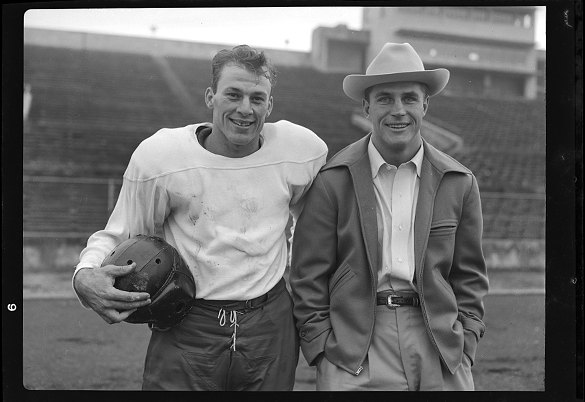

As the 1949 season came to a close, Justice with his brother Jack along with his good friend SMU All America Doak Walker, partnered with former Greensboro businessman George Edwards, who was president of Quality Textiles in Greenville, South Carolina, to take that T-shirt idea across North Carolina and Texas. Both Justice and Walker were triple-threat tailbacks—Justice in Coach Carl Snavely’s single wing, and Walker in Coach Matty Bell’s double wing. The white T-shirts came in three designs: running, passing, and kicking, with Carolina blue lettering for Charlie and SMU red lettering for Doak.

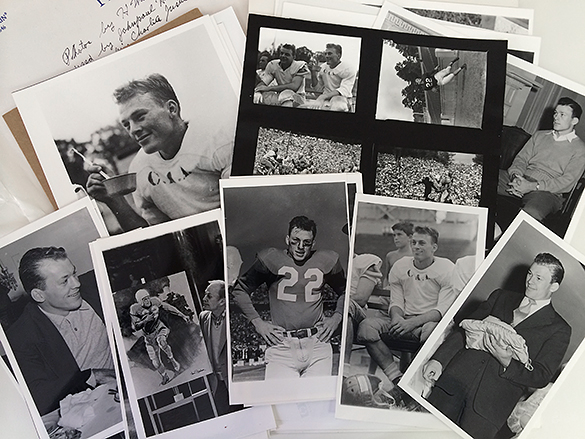

Hugh Morton was hired to take publicity pictures. Morton and Justice had been friends for a long time, and Justice and Walker had become friends while on several All America teams in ’48 and ’49. Morton always included one of the T-shirt shots in his slide shows.

Hugh Morton was hired to take publicity pictures. Morton and Justice had been friends for a long time, and Justice and Walker had become friends while on several All America teams in ’48 and ’49. Morton always included one of the T-shirt shots in his slide shows.

Following the ’49 bowl season, the two Saturday heroes started a series of personal appearance autograph parties. They were very careful not to enter into any kind of business venture until they had finished their college playing careers and were no longer under NCAA regulations.

Justice made his first stop at Meyer’s Department Store in downtown Greensboro on Monday January 9, 1950, one week after leading UNC in the 1950 Cotton Bowl in Dallas, and two days after leading the South team to victory over Walker’s North team in the first annual Senior Bowl played in Jacksonville, Florida. Charlie and Sarah arrived at the store about 2:15 for the 2:30 signing party. There was already a line. As Charlie began to sign the shirts, the line grew longer and by 3:30 with the school kids out of class, the line stretched out the door and down the sidewalk. By 4:30, the sidewalk was filled as far as one could see and overflowed into Elm Street. At 5:00 o’clock an estimated crowd between 2,500 and 3,000 people that were either in line or had been through the line since 2:15. Justice had worn out 6 pens signing his name. It was at this point that the Greensboro Police Department had to be called in. I didn’t even get close to Charlie that day, but I did get a shirt which I still have. Finally, at 5:30, they cleared the store and locked the doors. The store created a mail order form and advertised it in the Greensboro Daily News. (No web sites in those days). The shirts sold for one dollar each and the postage was fifteen cents.

A headline in the Greensboro Daily News the next morning read, “Choo Choo Mobbed by Adoring Fans.” A front page, four-column story by Daily News staff writer Larry Hirsch was accompanied by two pictures, one of which was titled “The Meyer’s Bowl.” There is also a picture of the Greensboro signing party in the 1958 Bob Quincy–Julian Scheer book Choo Choo: The Charlie Justice Story. In a 1984 interview Justice recalled, “I had hoped to sign a few autographs and help Ken Blair, manager over at Meyer’s sell a few T-shirts.”

Two days later, on January 11, Justice was at the J. C. Penney Company in Burlington for another autograph party—a party that was documented by Morton photographic contemporary Edward J. McCauley and his images from that day are also in the North Carolina Collection at UNC. Woody Durham, the “Voice of the Tar Heels,” likes to tell about being at that party in Burlington.

In the 14 January 1950 issue of The State, the magazine’s editorial staff asked readers for nominations for their “North Carolina’s Man of the Year” award for 1949. They wrote,

Pick out some man and then weigh him in the balance. Compare the good things he has done with others that might not be so good. Decide whether he has been an influence for those things which tend to promote the welfare of North Carolina and its people. It is on that basis that the selection should be made.

Two weeks later, the January 28th issue of the The State hit magazine racks and mail boxes across North Carolina. On the cover: the Charlie Justice family, photographed by Hugh Morton.

Inside the magazine, editors noted that Justice and Governor W. Kerr Scott received the most mention from readers. The editors expounded on their selection of Justice (which you can read in its entirety by clicking on the magazine cover above):

Inside the magazine, editors noted that Justice and Governor W. Kerr Scott received the most mention from readers. The editors expounded on their selection of Justice (which you can read in its entirety by clicking on the magazine cover above):

. . . there are two major classes of people in North Carolina—the young and the old. Both are important. Perhaps the young are more important because they still have the major portion of their lives ahead of them. Charlie Justice has been an inspiration to many thousands of boys and girls in North Carolina. You’d be surprised to know how many of them keep scrap-books about him. They actually swap pictures, just as we used to swap cigarette pictures fifty years or so ago.

Summarizing they listed their reasons for their selection:

- He has been the finest kind of an inspiration and example to the youth of North Carolina.

- He has provided many hours of pleasurable entertainment to hundreds of thousands of people.

- He has given North Carolina national publicity of a most favorable nature.

- He has been unselfish in his willingness to be of service in may worthy causes.

- He has never been to busy to be nice to kids.

A few days after the Man-of-the-Year issue of The State, on February 3rd, Justice attended another autograph party, this one at Belk-Tyler’s in Rocky Mount.

A bit later in 1950, Doak Walker was having similar successful autograph parties in the Dallas–Fort Worth area of Texas. On April 14, 1950, he appeared on the evening news on KBTV, Channel 8 in Dallas promoting his autograph party at Titche-Goettinger the following day. The store also set up a mail order and phone-in ad in the Dallas Morning News. A. Harris & Company set up a mail-order blank for the shirts in the “News” as well. The Robert I. Cohen department store place an advertisement in the April 15th edition of the Galveston Daily News that read, “Hey Fellas, (gals, too) Be the first in your gang to wear a DOAK WALKER TEE SHIRT $1.” The advertisement gave a description of the three pictures styles, included a drawing of a lad wearing the running shirt and a note that “Phone and Mail Orders Accepted”—plus an announcement they would be giving away ten autographed footballs when “The Doaker will be here personally for an autograph party Saturday, April 19th. Don’t miss him.” Another advertisement with a drawing of a kid wearing the passing T-shirt ran in the 23rd issue of the newspaper. Several weeks later, a May 27th Cohen advertisement for a one-day, end-of-the-month clearance sale priced the T-shirts at 88¢.

It not clear how widely Morton’s photographs were used for publicity. I have pasted in one of my Charlie Justice scrapbooks, a newspaper picture of the Morton image that shows both wearing the shirt with both player pictures and the caption reads:

Two pals certain to succeed when their classes graduate in June are Charlie Justice left the Carolina All America, and Doak Walker right SMU’s All America. They’ve already gone into business for themselves as witness the shirts. They plan a personal appearance tour together after graduation.

I can’t tell which newspaper or the date of the clipping. Likely it would have been The Greensboro Daily News, sometime after January 2nd and before June of 1950. I don’t believe the joint tour took place because it was scheduled to begin after Carolina’s final regular season game with Virginia on November 26th, but since they got the ’50 Cotton Bowl bid, the joint tour was canceled. I don’t believe it was ever rescheduled. Surveying various Texas and North Carolina newspapers for 1950 that are available online did not yield an answer.

The Justice jerseys were available into the following football season, too. Quality Textiles placed advertisements in game-day programs that listed stores in North Carolina and Virginia that sold the shirts. Rather than using the Justice/Walker photographs, the ad used photograph of a young boy and girl holding hands while wearing Justice jerseys. The photograph shows that the manufacturer also made a long sleeve polo shirt, which may explain why they choose to make different image.

Thirty-four years after the T-shirt’s debut, in August of 1984, I was assigned to direct a Charlie Justice documentary produced by Winston-Salem TV producer David Solomon. (Many may remember Solomon as having worked with Hugh Morton on the 1994 PBS documentary The Search for Clean Air.) As part of the promotion campaign for the Justice program, the 1949 Choo Choo T-shirt was replicated and given to the media to promote the program, “All the Way Choo Choo.” This time I got Charlie to autograph my shirt.

Dismal Day in Dallas

Head Coach Larry Fedora’s 2014 Tar Heels are going bowling.

For the 31st time, going back to 1947, UNC’s football team will play in a post season bowl game—this time it’s the “Quick Lane Bowl” in Detroit on Friday, December 26th at 4:30 PM (ET). The game will be on ESPN.

Of the 30 bowl games played, the Tar Heels have been victorious 14 times. Of the 16 losses, the one on January 2, 1950 was one of the toughest. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard looks back on that dismal day in Dallas, almost 65 years ago.

When UNC Head Football Coach Carl Snavely arrived at his 215 Wollen Gym office on Wednesday, November 23, 1949, a New Year’s bowl game was not on his radar. After all, Carolina had lost 3 games during the season and two of those losses were decisive: Notre Dame 42 to 6 in Yankee Stadium and Tennessee 35 to 6 in Kenan Stadium.

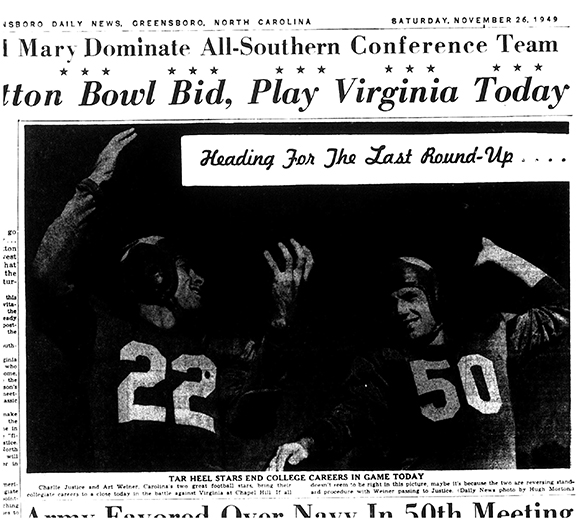

Coach was concentrating on the upcoming game with Virginia three days away. Then, the phone rang and everything changed. It was Dan Rogers, Chairman of the Board, Cotton Bowl Athletic Association, calling from Dallas. He told Coach Snavely that Carolina was on a short list for a Cotton Bowl invitation. He then added, Virginia is on that list also. So the UNC vs. UVA game on Saturday, November 26, 1949 would now become the “Cotton Bowl Invitational,” with the winner going to the top of the list and getting the bid.

Snavely told his team about the phone call when the varsity was traveling by bus to the Duke–Carolina freshmen game in Durham on Thursday, the 24th. The next day the team voted to accept the bid if offered.

The Greensboro Daily News on Saturday morning featured a large Hugh Morton photograph of UNC All-Americas Charlie Justice and Art Weiner. The headline caption read “Heading for the Last Roundup.”

On Saturday, November 26, 1949, the largest football crowd in Chapel Hill to date—48,000—gathered in ideal football weather to see Justice and Weiner play their final varsity game in Kenan Stadium. Veteran CBS Radio broadcaster Red Barber was in town to call the game.

On Saturday, November 26, 1949, the largest football crowd in Chapel Hill to date—48,000—gathered in ideal football weather to see Justice and Weiner play their final varsity game in Kenan Stadium. Veteran CBS Radio broadcaster Red Barber was in town to call the game.

Tar Heel fans were not disappointed.

After a scoreless first quarter . . . two plays into the second quarter, it was Justice on a typical, zigzagging run off left guard for a 14-yard touchdown and Carolina led 7 to 0 following Abie Williams’ point after. At the 13:30 mark it was Justice again, this time a 63-yard touchdown pass to Weiner. Williams was true again on the PAT and Carolina led 14 to 0 at the half.

Twelve high school bands were on hand to entertain during halftime. The game was dedicated to William Rand Kenan, Jr., who had donated the stadium in 1927. He was a special guest on this day.

The third quarter, like the first, was scoreless, but in the fourth quarter, Virginia was able to put together a 43-yard drive and was finally on the scoreboard with 2:30 remaining in the game. Carolina accidentally touched Virginia’s on-side kick and UVA took over at their own 48. Four plays and two first-downs later, Virginia was at the Carolina 7-yard line with 0:32 on the clock. Three Cavalier passes failed; on fourth down they tried a double-reverse play, but Tar Heels Art Weiner and Roscoe Hansen stopped the ball carrier back on the 8-yard line to seal the victory.

Following the game, Sports Information Director Jake Wade made the announcement: the Heels had been invited to play in the Cotton Bowl, and the team and the University administration had approved. Carolina, the Southern Conference Champion, would play Rice Institute (Rice University today), the Southwest Conference Champion on January 2, 1950.

Snavely ordered a break for his troops from November 28th until December 3rd. A week of practice followed, then a break for exams. Preparation for Rice would resume on December 16th and continue until the Christmas break on December 21st.

The Tar Heel team reassembled in Chapel Hill on December 26th and held one final practice on the 27th before departing for Big D.

It was cold and clear at Raleigh-Durham Airport at 9:35 AM on December 28, 1949, when the first of two planes carrying the Tar Heel football team took off for Dallas. The Capital Airlines DC-4 was labeled “Cotton Bowl Special,” and carried Justice and Weiner plus 46 other UNC players and part of the coaching staff. Then at 2 PM, the second plane carrying the remainder of the team and staff took off. On hand for both takeoffs was Chapel Hill Mayor Ed Lanier.

The first flight arrived in Dallas at 4:25 PM and was greeted by 3,000 Tar Heel fans and coeds from SMU plus Mr. SMU himself, Doak Walker. Originally, Charlie and Sarah Justice were going to stay at the Melrose Hotel with the coaches and team, but Justice got a letter a week earlier from Doak Walker inviting them to spend the week at the Walker home.

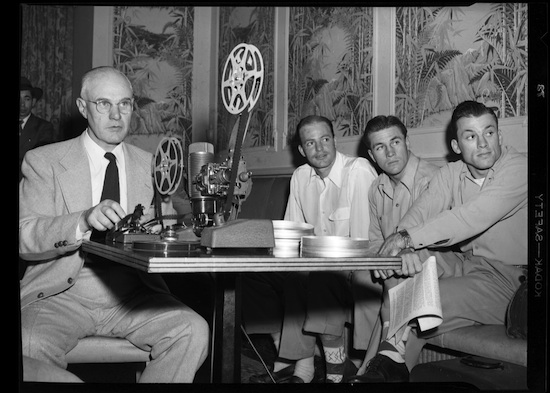

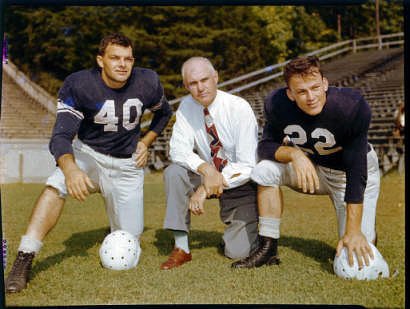

December 29th was a practice day for Carolina . . . a workout at Dal-Hi stadium in the morning and movie viewing in the afternoon. Walker was present for both sessions, adding coaching suggestions along the way since he had already played Rice earlier in the season. Morton’s picture of Justice, Walker, and Snavely viewing game movies made the papers back in North Carolina on December 30th.

Also, early on the morning of the 30th, the football team got the good news from Chapel Hill that Carolina’s basketball team had upset Duke 59 to 52 in the first annual Dixie Classic back in Raleigh the night before.

Also, early on the morning of the 30th, the football team got the good news from Chapel Hill that Carolina’s basketball team had upset Duke 59 to 52 in the first annual Dixie Classic back in Raleigh the night before.

Following an afternoon practice, Coach Snavely said: “Right now we are in the best condition for the ball game this season. The boys are in good spirit and I know they are having a good time here in Dallas.”

The Carolina team and coaches along with photographer Hugh Morton attended the annual Cotton Bowl luncheon put on by the local Optimist Club on Saturday the 31st. The keynote speaker was Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark, a native of Dallas.

The Sunday papers predicted clouds and a 7-point win for Rice on Monday. Back home, The Greensboro Daily News published on the front page of the Sports section a picture of Justice and Bob Gantt at work on the practice field. It was now time to get serious about the 14th Annual Cotton Bowl.

Monday, January 2, 1950 was a cold, damp day in Asheboro, North Carolina. I remember sitting with my best buddy on the front steps listening to the game on his portable radio that he had gotten for Christmas. Legendary NBC sports broadcaster Bill Stern was the play-by-play announcer with analysis and color by Kern Tips. We were listening to station WBIG in Greensboro. (The game was also on WSJS radio in Winston-Salem). The Greensboro Daily News headline that morning read:

“JUSTICE ERA COMES TO AN END AS TAR HEELS BATTLE OWLS IN COTTON BOWL”

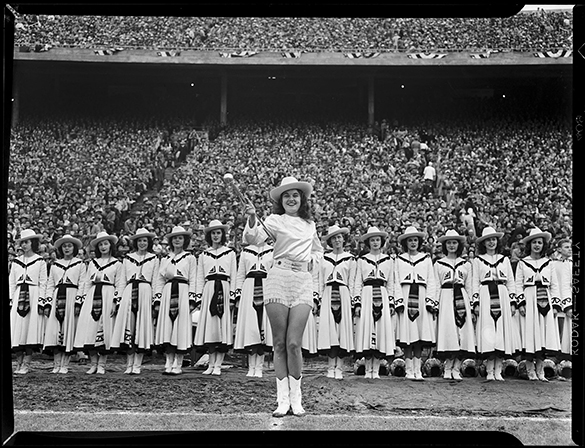

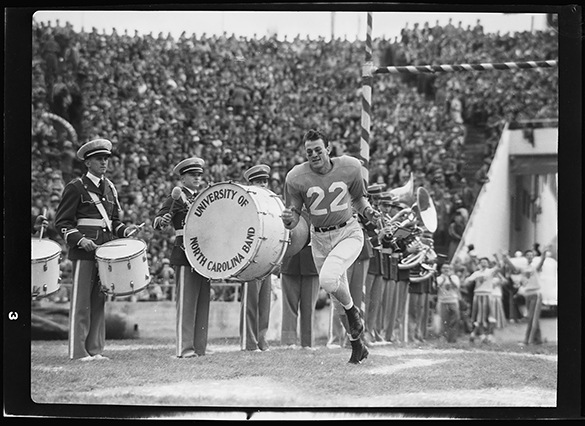

The University of North Carolina Band, under the direction of Prof. Earl Slocum was part of the pre-game festivities as Charlie Justice ran onto the field for the final time in a Carolina varsity uniform. Morton’s image of Justice and the band is the first picture in the 1958 Quincy-Scheer Justice biography (on page 3).

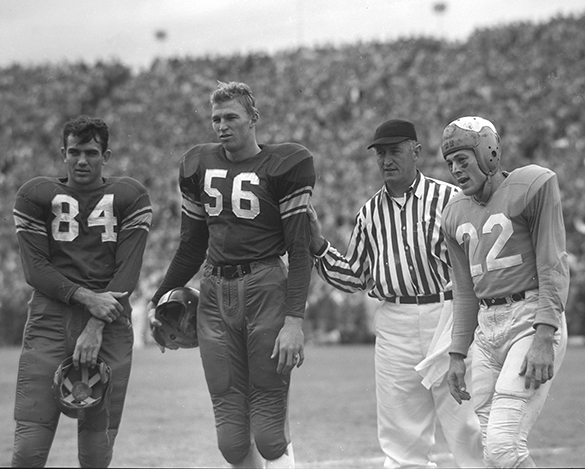

Then as 75,347 fans watched, UNC Captain Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice met at midfield with Rice Co-Captains James “Froggy” Williams and Gerald Weatherly for Referee Ray McCullock’s coin toss. Hugh Morton documented that scene as well before returning to his Carolina sideline position.

Gloomy skies prevailed as neither team could do much in the first quarter of play which ended with neither team on the scoreboard. Early in the second quarter, Rice quarterback Tobin Rote passed to Billy Burkhalter for a 44-yard touchdown. Later in the quarter, Rice took possession at midfield and drove for a second score with fullback Bobby Lantrip going the final three-yards to make the halftime score 14 to 0.

The halftime show, directed by Frank Malone, Jr. featured the Rice Institute Band plus nine high school bands from the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The highlight of the show was a performance by the Apache Bells of Tyler Texas Junior College and finally the presentation of the 1950 Cotton Bowl Queen, Miss Eugenia Harris from Houston.

When the third quarter began, Rice picked up where they left off, this time it was a 17-yard pass from Tobin Rote to “Froggy” Williams to make the score 21 to 0 with 15 minutes to play.

Early in quarter number four, following an interception at the Carolina 15, Rice, on two plays, scored their final points of the day when Burkhalter scored his second touchdown of the afternoon. With 9 minutes remaining, the score was Rice 27 – Carolina 0.

At this point, Carolina seemed to come alive. They drove 65 yards—the final 7 yard a touchdown pass from Justice to Paul Rizzo. During this drive, Morton took one of his most famous Charlie Justice pictures. The image is part of the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives exhibit, “Photographs by Hugh Morton: An Uncommon Retrospective.”

Then Carolina put on another drive—this one 80 yards— and fullback Billy Hayes accounted for 41 of them. The final play of the drive came when Justice went off left tackle, but Rice defensive end Billy Taylor grabbed him by the sleeve. Justice tossed the ball to his left where Rizzo caught it and raced into the end zone. Abie Williams’ extra point made the final score 27 to 13. The Carolina comeback was too little, too late.

Then Carolina put on another drive—this one 80 yards— and fullback Billy Hayes accounted for 41 of them. The final play of the drive came when Justice went off left tackle, but Rice defensive end Billy Taylor grabbed him by the sleeve. Justice tossed the ball to his left where Rizzo caught it and raced into the end zone. Abie Williams’ extra point made the final score 27 to 13. The Carolina comeback was too little, too late.

Following the traditional coaches handshake at midfield, each coach commented on the game. Rice head coach Jess Neely simply said, “I had figured we could run against North Carolina.” And run they did—226 yards to 174 for UNC. Tar Heel head coach Carl Snavely said, “We simply did not have a bowl team this year.”

Charlie Justice, in a 1995 interview with biographer Bob Terrell, said, “We didn’t deserve the bowl trip. The Cotton Bowl invited us so my playing could be measured against Doak Walker, who had a great season at SMU. Texans had seen Doak play all season but hadn’t seen me, so this gave them the opportunity.”

Carolina and Rice each got a check for $125,951, while the players each got engraved Cotton Bowl watches and beautiful Cotton Bowl blankets.

On Wednesday, January 6th, Hugh Morton’s post-game picture of Charlie Justice and Paul Rizzo graced the sports page in The Greensboro Daily News. The picture also turned up in the 1950 UNC yearbook, the “Yackety Yack” on page 271.

The game was not national televised, but even if it had been, North Carolina’s two TV stations at the time, in Greensboro and Charlotte, would not have been able to carry it because the AT&T cable had not been completed in the state. That would come nine months later on September 30, 1950.

So WFMY-TV in Greensboro made arrangements to get NBC-TV to film the game, then fly the film back to Greensboro for showing. WFMY Sports Director Charlie Harville would narrate the film. The showing was scheduled for 9:30 PM on Wednesday, January 4th. However, rainy, foggy weather in Dallas prevented the plane carrying the film from taking off, so the showing had to be delayed until 9:30 PM on Thursday. Folks from all across the state came into Greensboro to watch. It turned out to be the largest single audience in the history of television in North Carolina at that time. The program was so popular, the station repeated the film on Friday, January 6th. If Carolina could have won, the station probably could have made an unprecedented third showing.

In his own words: Johnpaul Harris, artist and dear friend

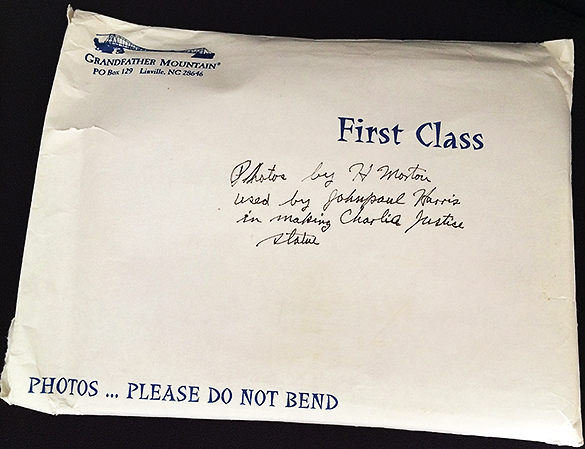

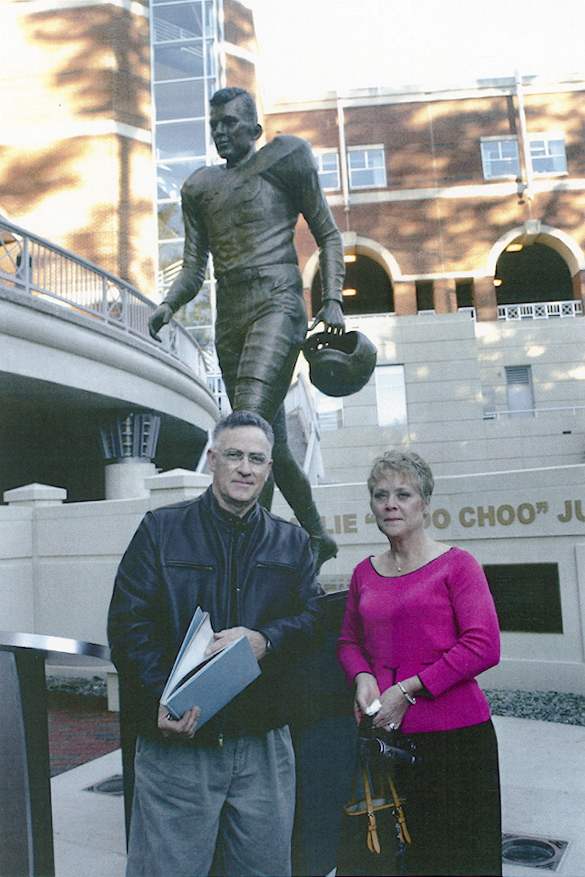

Today, November 5, 2014 marks a very special anniversary on the UNC campus. It was ten years ago, on a beautiful Hugh Morton photo-post-card-day, that the magnificent Charlie Justice statue was dedicated just outside the Justice Hall of Honor at the Kenan Football Center. On that day, the dedication ceremony included several people representing the university, plus friends and teammates—but we didn’t hear from the man who made it all possible: sculptor Johnpaul Harris. So, today on the tenth anniversary, Morton Collection volunteer Jack Hilliard shares some of Harris’ thoughts about that day and his work with his friend Hugh Morton.

I didn’t want to make him [Justice] too much of a pretty boy, but I didn’t want to make him this mean, killer football player either. —Johnpaul Harris in the February 6, 2005 issue of the High Point Enterprise.

Shortly after Charlie Justice’s death on October 17, 2003, teammate Joe Neikirk approached Hugh Morton with an idea for a statue. Morton, who had worked with his friend Sculptor Johnpaul Harris on other projects like the Mildred and cubs statue and the deer habitat at Grandfather Mountain, immediately called his friend to see if he would be interested in a football statue. Harris described his reaction in a 2005 letter to Hugh Morton:

“I probably more than anybody know how Coach (Carl) Snavely felt when Charlie turned up at Chapel Hill. If it wasn’t a gift from God for Snavely it was certainly one for me. You called me late in 2003 to see if it was the kind of project I would be interested in. I think you knew the answer, but maybe not the extent of it. It was the ultimate project for a man who was an OK football player who in high school knew nothing of Charlie Justice other than that he was the first famous ball player that I or any of my generation remember.”

In an interview with Annette Dunlap in the November 19, 2004 issue of Asheboro’s The Courier-Tribune, Harris said, “I jumped on it.” Morton then became the linchpin between the university and Harris. “There’s a lot of red tape established on the Chapel Hill campus for the installation of artworks,” Harris continued in his Dunlap interview. “I just had to wait for it to run its course.”

While he waited, Harris and Morton started to work on the project . . . as Harris continues in his letter to Morton:

“. . . you started sending pictures from your fantastic collection of Carolina images. I treasure each one for several reasons, but at the time they were just full of information that was vital to the project. When I asked for more particular angles, you always came through for me. It was like Christmas every time I opened the mail box to find a big white envelope with Grandfather Logo in the corner. I had enough information to do the job, but I never saw a picture that didn’t further my understanding of who Charlie Justice was.

“. . . Then one day the phone rang and it was Willie Scroggs (Senior Associate Athletic Director for Facilities at UNC) saying that they wanted me to do the Charlie Justice statue. It was the sweetest moment of my life as a sculptor, until the team reviews, and the unveiling.”

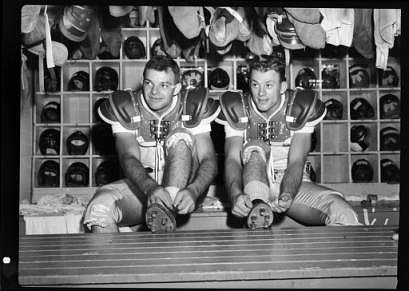

It was now time for serious work. Harris and Morton’s UNC committee selected the walking pose rather than an action shot and Harris prepared a 26-inch-model for Athletics Director Dick Baddour to review—a review that came on the day of the 2004 Blue-White game at Kenan Stadium. Harris was a special guest at the game.

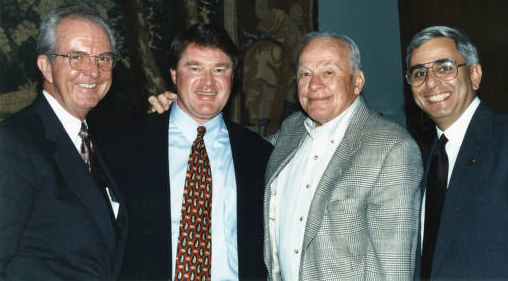

Next up, on June 1, 2004, was the first of two Justice-era player reviews. This was my introduction to Johnpaul Harris. We have remained good friends and get together for lunch every few weeks.

Harris continues with his letter to Morton:

I thought Charlie looked pretty good when the teammates came over to critique it.

The players offered suggestions and Harris took lots of notes. Three weeks later, the players had a second review in Harris’ Asheboro studio. Harris made final adjustments, then a final mold before Charlie was off to the foundry. On January 7, 2005 Johnpaul Harris was a guest on the UNC-TV program North Carolina People with William Friday. Harris explained the process of taking four, 30-gallon-barrels of North Carolina clay and making it into a work of art to be cast at the foundry.

As Harris wrote to Morton,

It felt really good to have Charlie in place and out of my hands for a change. I still enjoy seeing the pictures you made that day.

On Tuesday morning, November 2, 2004, I got a call from Hugh Morton. He said, “We’re going to put the Charlie Justice statue in place tomorrow morning. We’d like to have you there.”

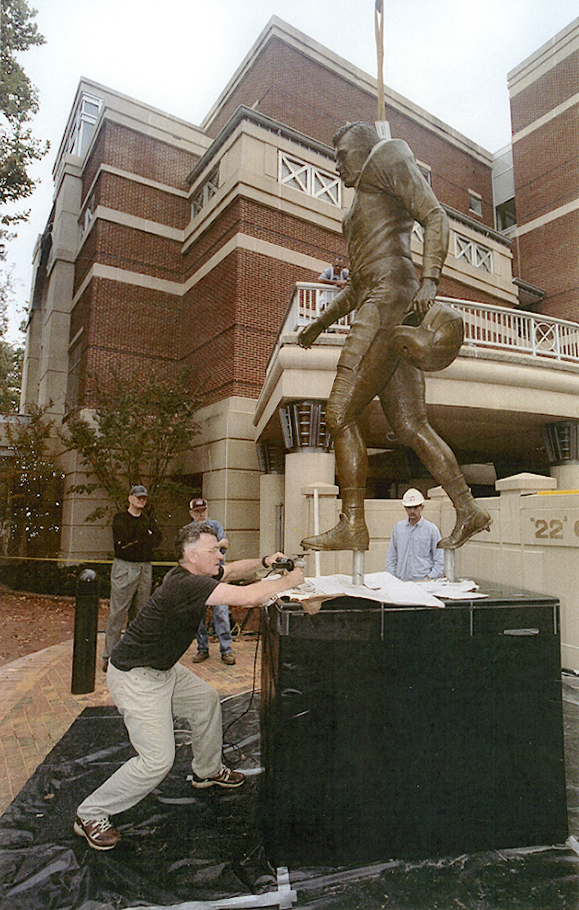

Wednesday, November 3rd was a beautiful day in Chapel Hill as Johnpaul Harris directed a crew from Architect Glenn Corley, and placed the 950 pound, 8 foot, 6 inch work of art into its final position. When all of the installation work was done, Hugh Morton said to Harris, “You did a magnificent job. It looks just like Charlie.”

On November 5, 2004 the Morton-Harris team was once again prepared to impress with the dedication of the Charlie Justice statue.

In his letter to Morton, Harris continued:

For me, days don’t come any better than unveiling day. The weather was perfect. There were so many friends and family, there was not enough time to do all the visiting I would have liked, not to mention catching up with Charlie’s teammates that I have come to know.

“It was great to see everybody enjoying Charlie after the unveiling. Barbara Crews (Charlie and Sarah’s daughter) seemed to enjoy it more than anyone else and for longer periods. I saw her staring up into the face and remarking that she hadn’t seen her Daddy from that perspective since she was a little girl. I’m sure it sparked a deep well of memories for her. She also mentioned that she had never seen his hands as open as they were, since they had suffered so many injuries (probably from pro ball). Thanks, Hugh, for introducing us. I did miss getting the definitive picture of you and me standing before the thing that we had spent so much time and energy on in the past two or three seasons. Maybe we can do that on some nice crisp Saturday before a home game.”

Unfortunately, that pictured never got taken.

I thought my football life was behind me. I never expected to tell anyone that I had been an All Central Tar Heel Conference player. But the most perfect completion of the circle of my gridiron days has been realized. A pretty good footballer from Troy (NC) was chosen to honor in bronze the memory of the greatest football legend of the 20th century from North Carolina. I was part of the team that was Charlie’s team and by extension, I became a part of Charlie’s team. Finally, I had to live up to your faith in me and then if there was anything else I had to satisfy my own demands for my work. Thank you for making it all possible. Without the superb record that you shared with me, the work would have come far short of what we achieved. And thank you for your friendship, which started with our collaboration on Mildred. For my part I know that it will never end.

—Johnpaul Harris, February 5, 2005

Epilog

Morton and Harris had worked together about fifteen years before the Justice statue when Morton commissioned Harris to create a statue of Mildred the Bear, the loveable people-friendly mascot of Grandfather Mountain, with her cubs. That effort is now in the Grandfather Mountain Nature Museum. During a 2005 interview with Jimmy Tomlin in the High Point Enterprise, Harris remembered working inside Mildred’s habitat getting precise measurements. “She was great. Of course, they were keeping her happy with apple pieces while I was in there.” Harris also got to pet the cubs. “They’d put their paws around your neck and lick you in the face, just like a puppy.”

In addition to Mildred and Charlie, you can see other Johnpaul Harris sculptures at the North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro where there is an 11-foot Rhino statue. UNC Alumnus Charles Loudermilk funded for the city of Atlanta a Johnpaul Harris statue of former mayor Andrew Young for the city’s Walton Spring Park (now Andrew Young Plaza), installed in 2008.

Postscript

As Harris was driving his truck home from Chapel Hill following the review of his Justice model in May of 2004, the odometer tripped 222,222.2. When Johnpaul told Hugh the story about the 2s, He smiled and said, “Maybe somebody was trying to tell you something.”

I agree with Hugh. I feel sure that #22 saw that and smiled.

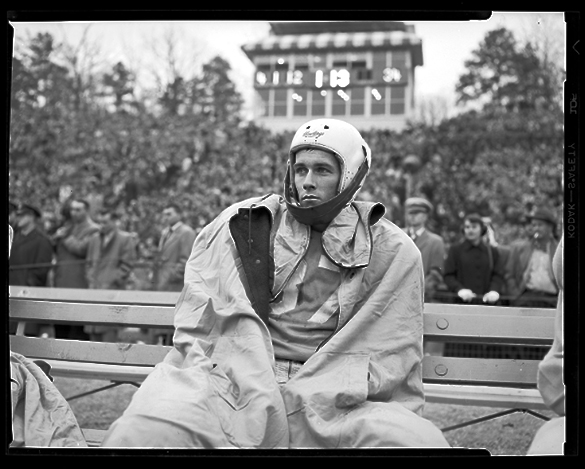

The eight-game season of 1952

On this day 62 football seasons ago, October 18, 1952, the UNC football team kicked off the 1952 season for a second time. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard explains how that happened and how a series of unique events made the ’52 season unlike any other.

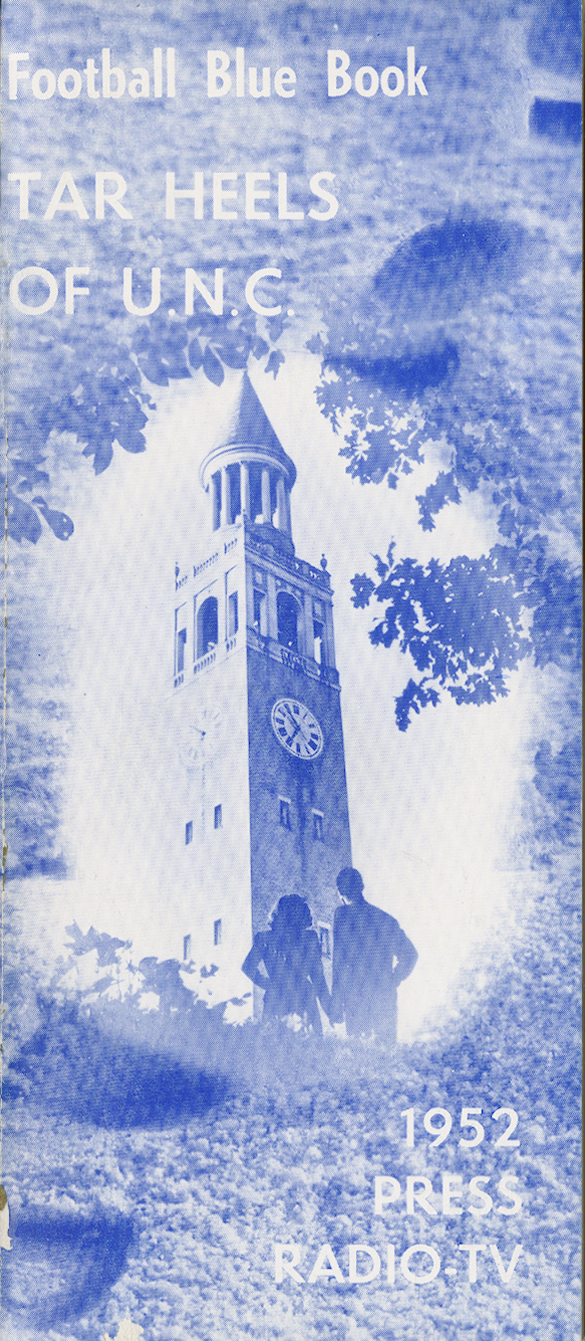

When the February 4, 1950 issue of The State, with Duke Chapel pictured on its cover, arrived in Hugh Morton’s mailbox in Wilmington, his immediate reaction was to quickly supply publisher Carl Goerch an “equal-time” photograph from UNC. The magazine printed Morton’s shot of the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower on its February 25th cover. In the early summer of 1952, when UNC Sports Information Director Jake Wade and his assistant Julian Scheer were preparing the ’52 football media guide (called a “blue book” in those days), they remembered Morton’s bell tower shot and decided to use it for the front cover of the ’52 guide. Inside, Wade talked about UNC’s chances for the upcoming football season, and Head Coach Carl Snavely’s switch from the single-wing to the split T-formation.

Snavely said, “We lacked the speedy, shifty tailbacks, tough blocking backs and interfering linemen so vital to the single-wing. We probably should have made the change a year ago.” Smith Barrier, writing in the 1952 Illustrated Football Annual, picked up the Snavely quote and added that twenty lettermen from the 1951 team had graduated.

Carolina began the 1952 season without much fanfare.

On Saturday, September 27th, the Texas Longhorns came into Chapel Hill for the first time since that “never-to-be-forgotten” day in 1948 when the Tar Heels were victorious 34 to 7 in a game many Tar Heels to this day call the greatest Carolina win . . . ever.

A sign hanging from Old East dorm read “Remember ’48,” but the events of September 25, 1948 were only a memory. Irwin Smallwood, writing in the Greensboro Daily News, on Sunday, September 28th, said, “Carolina’s hopes of a repeat of that great ’48 victory over Texas . . . lasted exactly five plays—no more.” Five plays into the game, Carolina fumbled. Texas recovered and never looked back, posting a 28 to 7 victory. 40,000 cheering Tar Heels, led by new UNC Head Cheerleader Bo Thorpe, along with the Elizabeth City Marching Band, and with Tar Heel football great Charlie Justice in the stands, and UNC All America Art Weiner at Snavely’s side on the bench. All that was not enough.

Next on the schedule was Georgia in Athens, but that encounter would never happen.

The front-page headline in the Greensboro Daily News on October 3rd read, “University Cancels Two Grid Contests as Polio Strikes.” The games with Georgia and NC State were canceled when UNC fullback Harold (Bull) Davidson came down with polio. Four additional students, all athletes, came down with the disease. Daily Tar Heel editor, Barry Farber, said, “the news is very depressing, but the only sensible step the University could take.”

Down in Athens, Georgia Head Coach Wally Butts said, “we are very disappointed that our traditional game with North Carolina can’t be played. We feel they were right to cancel the game under the circumstances.”

During the next two weeks, students were urged to stay on campus and long distant telephone calls to and from Chapel Hill doubled as students and anxious parents kept in touch.

In the end, all five students, football player “Bull” Davidson, cross country teammates John Robert Barden, Jr. and Richard Lee Bostain, swimmer Robert Nash “Pete” Higgins, and freshman football player Samuel S. Sanders, all recovered quickly and none suffered any paralysis.

So, on October 18th, it was time to kickoff the ’52 football season for a second time, with Wake Forest coming to town for the 49th meeting between the two schools, a series dating back to 1888.

Despite losing 6 of 11 fumbles, the Tar Heels led Wake 7 to 6 with 1:16 left in the game. But at that point Wake’s Sonny George kicked a game-winning- 22-yard field goal. New mascot Rameses VIII and 30,000 Tar Heel fans left Kenan Stadium dejected.

Next it was on to South Bend and a fourth meeting with Notre Dame. This one turned out just as the previous three had been…a Tar Heel loss. This time it was 34 to 14.

This interesting side-bar story appeared in the Greensboro Daily News on October 30, 1952:

It may be bad . . . but really, it’s not all that bad. Today (October 29th) Bo Thorpe reported to Coach Carl Snavely for football practice. Snavely appraised his new candidate as very fast and shifty. Thorpe is head cheerleader for Carolina’s Tar Heels, who have yet to win a game this season.

Time picked up the Thorpe story and ran it in its November 17th issue on page 132.

Here’s another interesting sidebar. Henry Benton (Bo) Thorpe started his first band in 1978. He and his band played for five presidential and gubernatorial inaugural balls, the National Symphony Ball, the Kentucky Colonel’s Derby Ball and for the annual June German, a traditional dance held in Rocky Mount. In all . . . at least 60 concerts a year.

For Carolina’s Tar Heels, a trip to Knoxville was next where they would be a three-touchdown underdog. Only 22,000 fans turned out for the game that saw the Volunteers swamp the Heels 41 to 14. The losing streak, going back to October 13, 1951 was now at 10—longest among the nation’s major colleges.

The University of Virginia was Carolina’s homecoming opponent on November 8, 1952. Their trip to Chapel Hill would be their only out-of-state venture in ’52, and they obviously made it count…a 34 to 7 blowout. A South Carolina homecoming game in Columbia was just ahead.

UNC freshman Flo Worrell, who had played on Carolina’s junior varsity team most of the ’52 season, stepped up and led the Heels to a much-needed victory over USC, 27 to 19. The losing streak was halted at 11 and Carolina fans looked forward to the traditional “battle of blues” slated for Saturday, November 22nd.

The weatherman promised 50-degrees and cloudy skies for the 39th meeting between Carolina and Duke . . . but he was wrong. 42,000 chilled fans saw Duke win the Southern Conference championship by shutting out the Tar Heels, 34 to 0. Carolina was never in the game.

With one game remaining, the Heels were 1 and 6. It had truly been a Tar Heel season out of focus. In seven games Carolina had scored five times on the ground and six times through the air—a total of eleven touchdowns. (In 1948, Charlie Justice personally scores 11 times in 10 games and passed for 12 more touchdowns).

The final game of the 1952 season was a Friday night affair in Miami’s Orange Bowl against the Miami Hurricanes. 20,222 fans came out and saw Carolina play its best game since a 40 to 7 win over William & Mary in October of 1950. During a 13- minute span in the second quarter, Carolina scored 27 points. The Alumni Review headline read, “34-7 Win Over Miami Provides Pleasing Finale.”

About 11:30 PM on Friday, November 28, 1952, the long ‘52 nightmare-season—a season like no other—was finally over. It was unique, as the record book shows:

- A 2-6 won-lost record

- No wins in Kenan Stadium

- 2 games canceled due to polio outbreak

- Midway through the season, Head Cheerleader Bo Thorpe turns in his megaphone for a football helmet

- Final game in the Southern Conference (the ’53 Tar Heels would play in the new Atlantic Coast Conference)

- Carolina scores 27 points in 13 minutes at Miami

The unofficial record book shows that world class photographer Hugh Morton documented all four of Carolina’s home games during the 1952 season. (He also photographed Duke’s home game against Georgia Tech.)

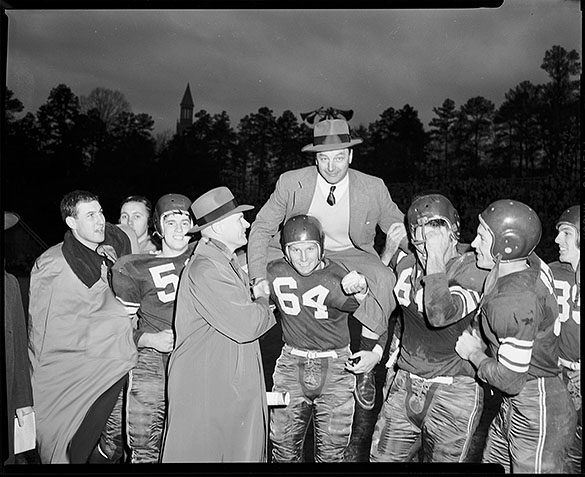

The University Athletic Council met at 8 PM on December 2 to decide the fate of Head Coach Carl Snavely. The coach had turned in his letter of resignation earlier in the afternoon. After 2 hours of discussion, the council accepted the resignation. Dean A.W. Hobbs, Chairman of the Council said, “The Council wishes to go on record as appreciating sincerely the fine services that Mr. Snavely has rendered the athletic association at the University of North Carolina.”

Carl Snavely left Chapel Hill in early 1953 and would not return to the campus until the “Charlie Justice Era” reunion during the weekend of October 29-31, 1971.

The good news from Chapel Hill in late 1952 was that new Head Basketball Coach Frank McGuire won his first game with the Tar Heels…a 70 to 50 win over The Citadel on December 1st.

There’s still a certain magic in the very name

On this day, May 18, 2014, UNC’s great All America football player, Charlie “Choo Choo” Justice, would have turned 90 years old. Justice was magical on the football field during the seasons 1946 through 1949 and that magic continued in his life after football. He has been featured in many posts here at A View to Hugh, and currently there are ninety-nine images in the online collection of Hugh Morton photographs that include or relate to Charlie Justice. Morton Collection volunteer and blog contributor Jack Hilliard looks at how the magic has evolved—and continues still.

When UNC’s classes of 1949 and 1950 held their respective 50th reunion celebrations in 1999 and 2000, they replicated their senior yearbooks, Yackety Yack. As part of the yearbooks, the reunion committees sent out questionnaires and asked the question, “What experience, event, place or time during your years at Carolina brings back particularly fond memories?” Of the 315 graduates who responded to the question, 126 mentioned the football team and 70 others mentioned Charlie Justice by name.

As part of the graduation ceremony on May 21, 2000, Charlie Justice was awarded the University’s highest honor, the degree of Doctor of Laws. The award citation contains the following quote from Charlie’s dear friend Hugh Morton:

No person will ever know the benefits that have come to our University as the result of the loyalty which Charlie Justice kindled in thousands of our alumni. The best thing about Charlie Justice, however, and the reason he deserves this honor, is that he has been a model citizen since college. He has contributed his fame to hundreds of drives and worthy causes and has generally and consistently served as a wholesome example to impressionable youth.

Due to his declining health, Justice was not able to attend the graduation ceremony, but his Tar Heel teammate Paul Rizzo accepted the honor for him.

In 1999, forty-nine years after he played his final varsity game as a Tar Heel, Charlie Justice was honored as “athlete of the century at UNC,” by readers of The Daily Tar Heel. Ten years later in 2009 he was declared the “Mount Rushmore of Tar Heel Football” by ESPN and was inducted in the inaugural class of the Southern Conference Hall of Fame.

Two days after Justice’s 70th birthday, on May 20, 1994, Ron Greene, Sr., writing in The Charlotte Observer, said, “None has worn the mantle of hero more gracefully. . . . His name remains magic.”

Thirty-seven seasons had come and gone since UNC freshman Justice led his Tar Heels over Navy 21 to 14 in Baltimore Stadium on October 19, 1946; however, when Navy came into Chapel Hill on September 15, 1984, the Midshipmen’s radio network had only one request of Carolina Sports Information Director Rick Brewer. They wanted Charlie Justice as a halftime guest.

Hugh Morton and Ed Rankin, in their 1988 book Making a Difference in North Carolina, included the following quote from Legendary Tar Heel broadcaster Woody Durham:

“In all my associations in sports over the years, I have never known a person to wear the mantle of fame any better than Charlie Justice has. His story to me is one of the most amazing stories in all of sports when you think about the fact that it was 40 years ago when he achieved the stardom that he did, and today his name is still magic.”

Author Bob Terrell, in the 2002 edition of his Justice biography All Aboard: The fantastic story of Choo Choo Justice and the football team that put North Carolina in the big time! says, “Charlie Justice became a legend because of talent but also because of character and sportsmanship.”

In 1950, after his magical four years at Carolina, Charlie wanted to offer some kind of payback to his University, so he took a job with his friend and admirer Billy Carmichael at the North Carolina Medical Foundation. At the time, the Foundation was raising money to complete North Carolina Memorial Hospital. (That would be accomplished the following year). During his time at the foundation, Justice was pursued by George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins. At one point Marshall offered to send Justice a signed, blank check. “Fill in the amount,” he told Charlie. But Justice turned down the offer, saying he owed his University. Justice later joined the Redskins, but for a modest salary.

On the weekend before the 1979 football season kicked off, Tom Northington of the Greensboro Daily News interviewed Justice in his Greensboro office. Justice talked about how the game had changed during the 30 years since he played his final season as a Tar Heel.

“Something is missing,” said Justice. “Team spirit is not what it once was, there’s too much of this ‘I’ thing, too much individualism.”

When Charlie Justice scored a touchdown, there were no “look-at-me” celebrations . . . no throwing the ball into the stands . . . no dunks over the goal post—and in those days, spikes were things that fastened railroad ties. I recall a 60-yard Justice touchdown in the 1950 College All-Star game before 88,885 fans at Soldiers’ Field in Chicago. After he crossed the goal line, he handed the ball to the official, and then trotted back up the field to shake hands with guard Porter Payne from the University of Georgia who had thrown the block that made the play possible.

On October 18, 1986 Charlie and Sarah Justice, along with some family members and friends, were in Kenan Stadium for a sold-out NC State game. As the group walked around the stadium other friends joined in and by the time they got up to the gate, Charlie realized he was one ticket short. At that point Justice could have made one of those signs that reads “Need One,” but Charlie didn’t do that. According to UNC General Alumni President, Doug Dibbert, Justice “could have walked into the stadium without tickets or placed a call to any number of people who would have provided him tickets, but Charlie would never want to impose upon anyone.” So, Charlie Justice made sure that all in the group got seated in section 19B, row AAA, and he then returned to the Carolina Inn and watched the game on TV.

On September 28, 1996 the actual 50th anniversary of the beginning of the “Charlie Justice Era” at Carolina, A.J Carr of Raleigh’s News & Observer, wrote a three-page profile of Justice. Said Carr: “He walked humbly on campus but ran historically on the football field, lifting the spirits of a school, a town, and an entire region.”

Carr interviewed then UNC Chancellor Michael Hooker who said: “There was a quality of magic about his name as I was growing up.”

In 1949, the Christian Athletes Federation honored Justice for his “humility in the face many honors.”

The 1973 football season marked the 25th anniversary of the magical Tar Heel season of 1948, a season that saw the Heels ranked number one in the country for the first and only time—an undefeated season with wins over Texas, LSU, Tennessee, and Georgia plus wins over NC State, Wake, Duke, Maryland and Virgina. Justice and Art Weiner were consensus All America with Justice as first runner-up for the Heisman Memorial Trophy and named national player of the year, and a team invitation to the Sugar Bowl on January 1, 1949 in New Orleans.

To celebrate that 25th anniversary, Ed Hodges did a Justice feature in the Durham Morning Herald on July 22nd. In the piece, Hodges said, “he (Justice) has in some magic way interwoven the past with the present.”

Woody Durham, then Sports Director at WFMY-TV in Greensboro, presented a two-part Justice documentary on September 16th and 23rd. That program not only aired on WFMY, but was also broadcast on WRAL-TV in Raleigh.

And Ron Fimrite, writing in the October 15, 1973 issue of Sports Illustrated, described the reaction to the famous 43-yard Justice TD run in the ’48 Duke game:

(As Justice crossed the goal), a fan, in the temporary end-zone seats was so excited by the amazing run that he fell forward onto the field. The crowd was alive, roaring, slapping each other. Coach Snavely, normally an impassive man, rushed from the bench to grab Charlie by both shoulders and shake him. ‘Great,’ he kept saying. ‘Great.’ Charlie could hear only the cheers—‘Choo Choo, Choo Choo. He knew then that for him they would never really stop. And . . . they have not stopped. They never will.

One of those 1950 graduates who responded to the revised Yackety Yack survey question back in 2000, Walter Hobson Kirk, Jr. from Durham, said it best: “Charlie Choo Choo Justice – accepting fame with honor and humility.”

“Mighty Mites,” Morton, and millions of azaleas

The 67th Annual North Carolina Azalea Festival will be presented in Wilmington April, 9 – 13, 2014. World class entertainment and millions of azaleas will combine to welcome spring to the Tar Heel state again. Wilmington’s celebration of spring began in 1948 and each year celebrity guests have been an important part of the festivities. Morton collection volunteer/contributor Jack Hilliard takes a look at a special group of celebrities that came to the New Hanover County port city back in the 1950s.

A Prologue:

When the 1950 College All-Star football team reported to training camp at St. John’s Military Academy in Delafield, Wisconsin on Thursday, July 20, 1950, UNC’s great All America football star Charlie Justice met up with his old friend Doak Walker from Southern Methodist University (SMU) and new friend Eddie LeBaron from College of the Pacific (COP), which is now University of the Pacific. Justice and Walker had become friends over the years when both were on most of the 1948 and 1949 All America teams and both had been pictured on the cover of Life. Walker had been selected for the 1948 Heisman Trophy while Justice was first runner up. And when UNC was in Dallas for the 1950 Cotton Bowl, Walker had helped the Tar Heels prepare for a game with Rice Institute (now Rice University). Walker’s SMU team had played and lost to Rice, 41 to 27, on October 21st. Hugh Morton photographed Justice, Walker and UNC Head Coach Carl Snavely during one of the film screening sessions at the Melrose Hotel. Also, Justice and Walker had gotten into the T-shirt business in early 1950 and Morton had done their publicity pictures. Quarterback Eddie LeBaron had been selected All America in 1949 as well, and the three “country boys” hit it off. All three loved watermelon and on the first day of camp they staked out a small country store which sold melons. “Put one on ice every afternoon,” Charlie told the store owner, “and we’ll come by and pick it up.” So every afternoon after practice the trio walked to the store, purchased their chilled melon, took it outside and sat on the curb enjoying the treat.

When game day arrived on August 11, 1950, the three “Mighty Mites,” as they were called (each was under six feet tall and weighed less than180 pounds) took the World Champion Philadelphia Eagles down by a score of 17 to 7. Hugh Morton didn’t attend the All-Star game, but he always included a wire photo from it in his slide shows.

❀ ❀ ❀ ❀ ❀ ❀ ❀

Back in Wilmington after the War, I left town for a week, and while I was gone the local folks elected me chairman of the first Azalea Festival in 1948. —Hugh Morton, 1996

The Dallas Morning News issue of Saturday, March 18, 1950 featured the storybook, Friday night wedding of Doak Walker and his college sweetheart Norma Peterson. The story said the couple would leave for a wedding trip to Canada “early next week . . . and will take another trip to North Carolina soon after they return.” That North Carolina trip would be to the 1950 Azalea Festival in Wilmington, held March 30th through April 2nd.

Hugh Morton photographed Doak and Norma soon after they arrived in Wilmington. Hugh’s wife Julia said in A View Hugh comment back in 2009, “I do remember that Doak and Norma and Charlie and Sarah (Justice) stayed with Hugh and me. The festival didn’t have as much available money back in those days, and they were our friends.”

Charlie and Sarah Justice had been part of the 1949 festival. Charlie had crowned Queen Azalea II who was movie star Martha Hyer and many remember how the photographers covering that event had insisted that Justice kiss the Queen and he very obligingly followed through on the request. Morton’s photograph in The State for April 16, 1949 (page 5) showed Justice with lipstick on his face. (The original negative for this shot is no longer extant, but there is a similar negative made moments apart.)

During the 1950 festival, Morton took several pictures of Doak and Charlie, and Norma and Sarah: a beautiful shot of both couples at Arlie Gardens, and a shot from the parade on Saturday, April 1st. The parade image was reproduced in the 1958 Bob Quincy–Julian Scheer book, Choo Choo; The Charlie Justice Story, on page 112. The same picture was also included in the 2002 Bob Terrell book All Aboard, but with an incorrect caption. That image is on page 182. And of course, The State magazine issue of April 15, 1950 (page 3) included a Morton picture of Justice and Walker at the crowing ceremony where Justice passed the crown to Walker who crowned Gregg Sherwood as Queen Azalea III.

When Charlie and Sarah arrived in Wilmington for the 1951 festival, Hugh Morton had put in place a new event. On Saturday afternoon, March 31st, there was a special golf match at the Cape Fear Country Club. It was called “Who Crowns the Azalea Queen?” and it pitted broadcasters Harry Wismer and Ted Malone against football greats Charlie Justice and Otto Graham—nine holes—winners crown Queen Margaret Sheridan Queen Azalea IV. And the winners . . . Charlie Justice and Otto Graham.

The day following the 1950 All-Star game, Eddie LeBaron left for Camp Pendleton and Marine duty. He would spend nine months in Korea and would receive a letter of commendation for heroism, a Bronze Star and a purple heart. Lt. Eddie LeBaron was back home in time to accept Hugh Morton’s invitation to the 1952 Azalea Festival. Again, as in 1951, there was a “Who Crowns the Azalea Queen?” golf match. This time with ABC broadcaster Harry Wismer, writer Hal Boyle, bandleader Tony Pastor, and football greats Justice, LeBaron, and Otto Graham. The football guys won and would be part of the crowning ceremony for Queen Azalea V, Cathy Downs. A tightly cropped version of Morton’s crowning shot is also in Chris Dixon’s 2001 book Ghost Wave (unnumbered center picture page).

Later, in November, 1952, Hugh Morton took in a Washington Redskins game and photographed Justice, LeBaron, and Graham at Old Griffith Stadium.

In March of 1953, Charlie and Sarah Justice made their fifth Festival appearance as Alexis Smith became Queen Azalea VI on Saturday, March 28th.

Eddie LeBaron would return to Wilmington for the ‘58 Festival, along with Andy Griffith who crowned Queen Azalea XI, Esther Williams on March 29, 1958. Morton photographed LeBaron with Andy and NC Governor Luther Hodges.

The “Mighty Mites” were special Azalea Festival guests and were special friends of Hugh Morton, who in 1997, at the 50th Festival was honored with a star on the Wilmington Riverfront Walk of Fame and was the Festival Grand Marshal.

An Epilogue:

Doak Walker’s marriage to Norma Peterson ended in divorce in 1965 and four years later he married Olympic skier Skeeter Werner. They lived in Steamboat Springs, Colorado until his death as a result of paralyzing injuries suffered in a skiing accident. Walker’s death on September 27, 1998 came ironically 50 years to the day of his Life magazine cover issue.

Prior to the planning sessions for the Charlie Justice statue, which now stands outside the Kenan Football Center on the UNC campus, Hugh Morton visited the Doak Walker statue at SMU. Morton decided, unlike the Walker statue, that Charlie would not wear his helmet so everyone could easily recognize him.

Charlie Justice passed away on October 17, 2003 following a long battle with Alzheimer’s. Charlie’s wife Sarah died four months later.

Hugh Morton “slipped peacefully away from us all on June 1, 2006.” Those words from Morton’s dear friend Bill Friday.

Eddie LeBaron played professional football with Charlie Justice for two seasons with the Washington Redskins. After Charlie’s retirement, the two remained close friends. LeBaron participated in a Multiple Sclerosis Celebrity Roast for Charlie in 1980, and both were Hugh Morton’s guests at the Highland Games in 1984. Justice and LeBaron were also celebrity guests at the Freedom Classic Celebrity Golf Tournament in Charlotte in 1989 and 1990. LeBaron lives in Sacramento, California and continues to play golf in his retirement. Due to his diminutive size, 5 feet, 7 inches, and his leadership skills from his military service, he is often called the “Littlest General.”

Home for the Holidays . . . 1947

UNC head football coach Larry Fedora will be taking his Tar Heels to the Belk Bowl in Charlotte on Saturday, December 28th. The 2013 team qualified for bowl eligibility on November 23rd with a resounding win over Old Dominion—their sixth win of the season. The following weekend, a loss to Duke, gave the Heels a 6 and 6 record for the season.

The 1947 Carolina team finished their season with an 8 and 2 record, but didn’t go to a bowl. Morton collection volunteer and blog contributor Jack Hilliard looks back to that season with an explanation as to why the ’47 Tar Heels were home for the holidays.

Many old time-Tar Heel-fans, as well as coaches and players from 1947, have considered the ’47 team to be the best of the “Charlie Justice Era” and there is good reason for that: as head coach Carl Snavely’s prepared for their second season with Justice on his team, there were high hopes for another Southern Conference championship. UNC’s Sports Information Director Jake Wade, writing in the 1947 issue of Street and Smith Football Pictorial Yearbook, said “King Carl Snavely will have back almost all of his legions of doughty lads that showed their heels to the pack last autumn.”

The ’47 season got underway on September 27th when head coach Wally Butts brought his Georgia Bulldogs to Chapel Hill for a rematch of the Sugar Bowl that had been played about nine months earlier, which Georgia won 20 to 10. On this September afternoon, however, the Tar Heels came away with a 14-to-7 victory thanks to the passing of Walt Pupa and the catching of Bob Cox and Art Weiner. The 1947 football season was off to a good start.

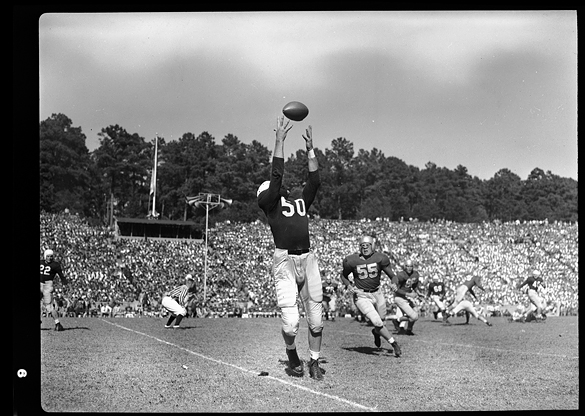

- UNC left end Art Weiner catches pass during game against Georgia at Kenan Stadium, September 27, 1947. UNC tailback Charlie Justice (left) looks on from a distance while Georgia’s Dan Edwards (#55) watches from a few yards away.

On Friday morning, October 3rd, a bus carrying the Tar Heel team arrived at Raleigh-Durham Airport, ready to make its first trip by plane, a trip to Austin, Texas to meet the University of Texas Longhorns led by standout quarterback Bobby Layne. The Douglas DC-4, a 50-passenger plane, cost the UNC Athletic Department $5,700 (almost $60,000 in today’s dollars).

Saturday, October 4th was a hot day in Texas—86 degrees to be exact—and the Tar Heels were dressed in those dark Navy shirts.

The only thing hotter than the Texas sun was the Texas team. Layne was as good as advertised as he led the Longhorns to a 34 to 0 win before 45,000 fans. It was the worst Tar Heel defeat since a loss to Pennsylvania 49 to 0 in 1945. In a 1992 interview, UNC All America End Art Weiner said, “I got so tired of hearing their band play “The Eyes of Texas are upon You.” (An interesting side note: One of Texas’ 2nd quarter touchdowns was scored by Tom Landry. He would become a hall of fame coach for the Dallas Cowboys). Some 2,000 Tar Heel fans, along with the band and cheerleaders, met the team at Woollen Gym on Sunday night at 7:40 as they returned home from Texas. The theme was upbeat and everyone looked forward to the Wake Forest game coming up in six days.

Wake came into Chapel Hill primed and ready, and took up where Texas left off the weekend before. When the dust settled, Wake had beaten Carolina 19 to 7. The only Tar Heel bright spot was Justice’s punting average: 51.5 yards per kick.

When the 1946 season ended, Carolina was ranked number 9; when “Peahead” Walker took his Demon Deacons out of Chapel Hill on October 11th, 1947, the Tar Heels had dropped out of the top 20 and two tough road games were just ahead.

The largest crowd in William and Mary football history to date packed Cary Field on October 18th for the game between the Indians (now they are called “The Tribe”) and the Tar Heels. The 20,000 fans were treated to a close game that was tied 7 to 7 after three quarters. Walt Pupa’s 1-yarder in the 4th quarter gave Carolina the win 13 to 7.

Next it was a train ride to Gainesville and a homecoming appointment with the University of Florida. On October 25th, Hosea Rodgers was brilliant, throwing three touchdown passes and running a 76-yard dash. Overall Rodgers amassed 245 yards and Carolina came away with a 35 to 7 rout. The Tar Heels were back on track, and Tennessee was coming over the mountains to Chapel Hill in a week.