I just happened to catch a news item that current Miss North Carolina Adrienne Core won the talent portion of the 2011 Miss America Pageant with “a fast-paced, contemporary clogging routine.” Many may already know that clogging is NC’s official state folk dance. I remember doing a bit of clogging (terribly) in my youth in Boone, and seeing some pretty amazing performances by clogging troupes, but I know nothing of the dance’s origins. According to Wikipedia,

Clogging is a type of folk dance with roots in traditional European dancing, early African-American dance, and traditional Cherokee dance in which the dancer’s footwear is used musically by striking the heel, the toe, or both in unison against a floor or each other to create audible percussive rhythms. Clogging was social dance in the Appalachian Mountains as early as the 18th century.

Fascinating to consider how those European, Cherokee and African American influences might have come together! From Wikipedia I also learn the interesting tidbit that “in the U.S. team clogging originated from square dance teams in Asheville, North Carolina’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival (1928), organized by Bascom Lamar Lunsford in the Appalachian region.” (Mr. Lunsford has been discussed on this blog a few times in the past, including in detail in one of our “Worth 1,000 Words” essays).

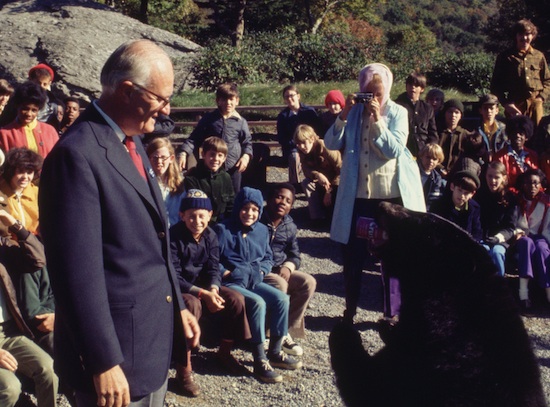

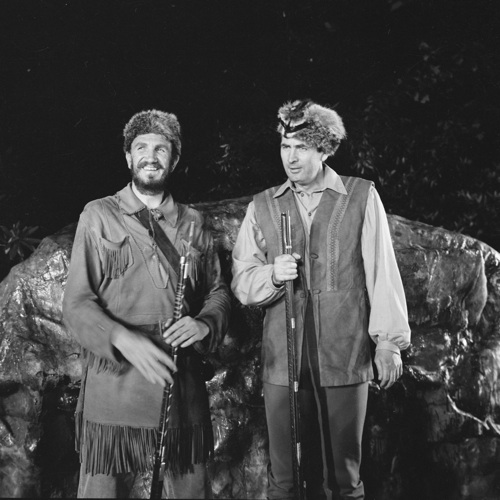

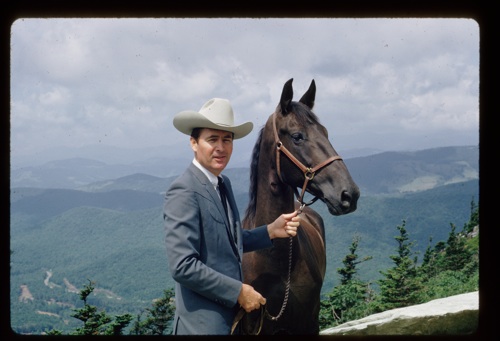

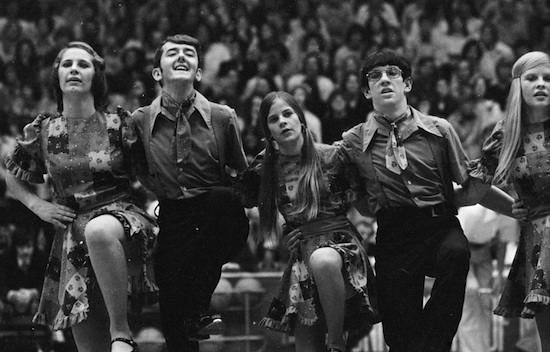

Hugh Morton took many photos of the world-renowned Grandfather Mountain Cloggers troupe, including the one above, which shows the Cloggers performing during halftime of a 1974 UNC-Maryland basketball game, and those below taken at the 1977 White House Easter Egg Roll and during the taping of a segment of Charles Kuralt’s “On the Road.”

I’m curious to learn more about the origins of the Grandfather Mountain Cloggers. Who founded the troupe? What became of it? Internet searches turn up little except for a very small Facebook group, whose description intriguingly invites “all those who were members back when clogging was a precision dance.” Is it no longer considered as such? Are there raging stylistic debates in the world of clogging? I’m dying to know.