Wilson Library has an impressive collection of materials related to Chang and Eng Bunker, the world-renowned 19th-century conjoined twins who lived in Wilkes and Surry counties in North Carolina. Unfortunately, it looks like we’ll have to pass on the latest Bunker artifact to come on the market. A recent article in the Winston-Salem Journal reported that the Traphill, N.C. farmhouse built by the Bunkers around 1840 is up for sale. The house features an extra-wide staircase and other custom modifications made for the brothers. With continued interest in the twins and their lives, I think that a house museum containing exhibits about the Bunkers and original or reproduction furniture (they had a bed large enough for four people to accommodate the twins and their wives) would certainly be a popular place.

Month: April 2007

Official State Blog?

I’m sure you’ve all heard the big news by now: the Bullfrog has been officially adopted as the State Amphibian of North Carolina.

Chapter 145 of the General Statues is devoted to “State Symbols and Official Adoptions.” The trend of adopting “official” symbols began in 1941, when the dogwood was adopted as the state flower. Since then, there have been some predictable choices, such as the state bird (Cardinal, 1943) and state language (English, 1987). But there have also been a few that are surely unique to North Carolina, including the state dog (Plott Hound, 1989) and the state carnivorous plant (Venus flytrap, 2005).

With the addition of the newly-crowned state amphibian, North Carolina is up to twenty-eight symbols and official adoptions, but there may be more on the way. There is legislation pending that would adopt an official State Collard Festival (in Ayden), a State Blackberry Festival (in Lenoir), and an Official Food Festival (the Lexington Barbecue Festival). This trend seems to have picked up speed lately, with half of our “official” state somethings being declared after 1990.

Carolina, The Blue Waves Are Breaking

While looking for something totally unrelated, I stumbled across this poem in the December 1853 edition of The North-Carolina University Magazine. For those Tar Heels who have had the unfortunate pleasure of emigrating elsewhere, this poem may make you hop the next flight back home.

Carolina, the blue waves are breaking,

Soft, soft on thy shell-spangled shore;

And the wild birds, their songs are making

In sweetness and gladness once more.

And the sun rays are softly reclining

On the sweet dimpled waves of thy tide,

And as gently are heaving and shining,

As the gems on the breast of a bride.

Carolina, mid the pines of thy wildwood

The breezes are passing away,

Like the fast fleeting memories of childhood,

Or the last dying tints of the day.

Carolina, I love, I adore thee;

Thy valleys, thy mountains and shore

Will e’er be in memories before me,

Altho’ I should see them no more.

Yet no matter what skies are above me,

Tho’ a wanderer to many a strand;

Carolina, I ever will love thee

And call thee my own sunny land.

By A. Perry Sperry (pseud.?). Greensboro, Nov. 10, 1853.

Anyone For a Smoke?

“This view shows the world’s largest pipe smoked by beautiful Wilson girls, during the North Carolina Tobacco Exposition and Festival held annually in Wilson, North Carolina.” — postcard caption.

I’m guessing that something like this wouldn’t go over too well these days, considering modern attitudes on smoking, but scenes like this were fairly common at tobacco festivals around the South, especially at the large annual event in Wilson. There is an excellent article by Blain Roberts on the origins of the “tobacco queen” in the 1930s in the Summer 2006 issue of Southern Cultures.

Happy Halifax Resolves Day!

On this day in 1776, North Carolina’s fourth Provincial Congress passed the Halifax Resolves, authorizing the state’s delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence from Great Britain. North Carolina was the first state to take this action.

Read more about the Resolves at the North Carolina Collection’s This Month in North Carolina History.

Squirrel Overpopulation

Recently, in the City of Santa Monica, California, officials came up with a novel way to control the squirrel population in Palisades Park. County officials are concerned that the squirrels pose a danger to public health, but the city wants a more humane solution to the problem than the usual method of euthanasia. Instead, they are opting to give the squirrels a contraceptive vaccine.

Public officials in North Carolina figured out a good way to deal with this problem a long time ago. In the 1760s, the General Assembly passed a law requiring certain citizens to kill the squirrels and crows who came across their paths. The law, entitled “An Act for Destroying Crows and Squirrels in the Several Counties therin Mentioned,” put a bounty on the heads of these pests. North Carolina legislators figured that with a little financial incentive, they could get all citizens to help in the efforts to solve the squirrel overpopulation problem.

To provide proof that they had done their civic duty, plantation owners and overseers in certain counties were required to bring at least seven crow heads or squirrel scalps to a justice of the peace for each taxable in his or her household. The penalty for a householder not killing his or her quota of pests was four pence for each animal, and the reward for killing more than the requisite number was also four pence per animal.

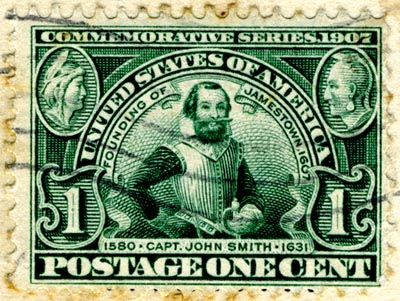

Celebrating Jamestown 1907 and 2007

Major anniversaries of historic events inspire us to look back not just at the event itself, but at the way we commemorated it in the past. I found this stamp on a postcard mailed in 1907, marking the 300th anniversary of the first permanent English settlement in North America.

As Virginia celebrates the 400th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, the U.S. Postal Service will issue a new commemorative stamp, showing neither John Smith nor imagined views of Native North Americans, but the three ships in which the British arrived. Much has changed since 1907, not least of which is the price of stamps.

This Way to Exit

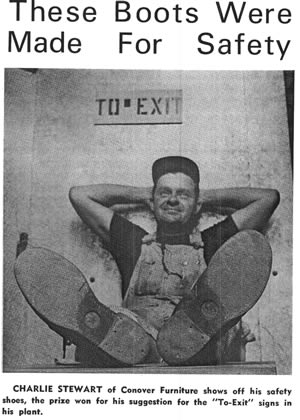

Next time you’re lost in a large and confusing building, and you find yourself relying on “Exit” signs to make your way out, thank North Carolinian Charlie Stewart for delivering you to safety.

Stewart was working at Conover Furniture when he suggested that signs with arrows pointing toward the nearest exit would be a boon to the safety and welfare of the factory’s employees and visitors. He was featured in the Summer-Fall 1970 issue of The Broyhill Outlook, a publication of Broyhill Furniture in Lenoir, N.C. There’s no evidence that this was the beginning of a nationwide trend, but I’d like to think so. For his suggestion, which has no doubt saved countless lives over the years, Stewart was awarded a new pair of boots.

April 1776: The Halifax Resolves

This Month in North Carolina History

North Carolina claims several contentious superlatives: first in flight (disputed by Ohio since Orville and Wilbur Wright lived in Dayton, Ohio), the first state university (disputed by Georgia since its university was chartered first, though North Carolina’s opened first), and the first declaration of independence, though most historians dispute the veracity of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Even with its questionable credentials, the date of the “Meck-Dec” still adorns North Carolina’s state flag. The other date on the flag, April 12, 1776, however, honors a first that no other state can claim, the “Halifax Resolves.” Though it was not an outright declaration of independence from Great Britain, this resolution, which was unanimously passed at the fourth Provincial Congress meeting in Halifax, North Carolina, was the first official action in which a colony authorized its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence.

Just eight months earlier, North Carolina’s official attitude toward independence was a bit more ambivalent. Facing increasing uncertainties and dealing with the divided loyalties of its populace, the third Provincial Congress issued an “Address to the Inhabitants of the British Empire.” This statement, which sought to justify congress’s actions (such as stockpiling weapons, raising units of soldiers, and preparing for self-government), denied that the colony desired to separate from Great Britain. It claimed allegiance to the crown, asserted that Parliament was at fault for passing undesirable legislation, and reiterated the colony’s desire to return to the relationship that existed between Great Britain and the American colonies in the years prior to the French and Indian War.

From August 1775 to April 1776, the deteriorating situation in North Carolina and other colonies changed how many North Carolinians and their delegates to the provincial congress viewed their relationship with Great Britain. Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, King George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and withdrew his protection from the colonists. In January 1776, royal governor Josiah Martin issued a call for loyalist troops to assemble and rendezvous with a contingent of the British army that was sailing for North Carolina’s coast. Though patriot militia and Continental Line soldiers intercepted the loyalists and routed them on February 27, 1776, at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, the skirmish still sent shock waves through the province. In addition, British agents continually worked to incite Native Americans, including the Cherokee, along the colony’s frontier, while along the coast, the British navy maintained several war ships. These events and several others forced North Carolina’s patriot leaders to the conclusion that reconciliation on amiable terms was no longer possible.

After the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, the fourth Provincial Congress convened in Halifax on April 4, 1776. Over the first few days, the congress organized itself and formed committees to oversee aspects of the province’s government and military preparations. On April 8, 1776, it created a select committee to consider the “Usurpations and Violences attempted and committed by the King and Parliament of Britain against America, and the further Measures to be taken for frustrating the same, and for the better Defence of this Province.” Four days later, on April 12, the group, which consisted of Thomas Burke, Cornelius Harnett (chairman), Allen Jones, Thomas Jones, John Kinchen, Abner Nash, and Thomas Person, presented a report detailing British atrocities and American responses. The committee believed that further attempts at compromise and reunion would fail, and they offered the following resolution:

That the Delegates for this Colony in the Continental Congress be impowered to concur with the Delegates of the other Colonies in declaring Independency, and forming foreign Alliances, reserving to this Colony the sole and exclusive Right of forming a Constitution and Laws for this Colony, and of appointing Delegates from Time to Time, (under the Direction of a general Representation thereof) to meet the Delegates of the other Colonies, for such Purposes as shall hereafter be pointed out.

The full congress took the recommendations into consideration and unanimously approved of them. The resolution was immediately copied and sent to Philadelphia, where Joseph Hewes, a member of North Carolina’s delegation, shared it with other American representatives. Soon thereafter, other colonies followed North Carolina’s lead, and the foundation was laid for the summer of 1776.

Sources

R. D. W. Connor. “North Carolina’s Priority in the Demand for a Declaration of Independence.” Reprinted from the South Atlantic Quarterly, July, 1909.

Robert L. Ganyard. The Emergence of North Carolina’s Revolutionary Government. Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1978.

The Journal of the Proceedings of the Provincial Congress of North Carolina, Held at Halifax on the 4th Day of April, 1776. New Bern, NC: Printed by James Davis, 1776.