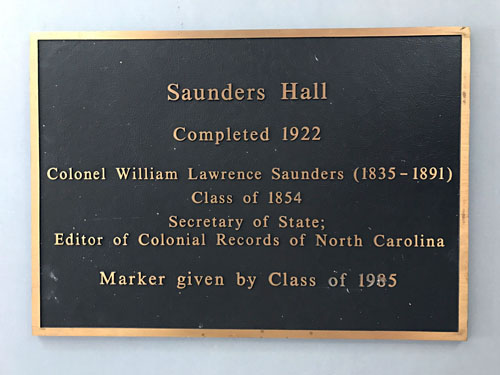

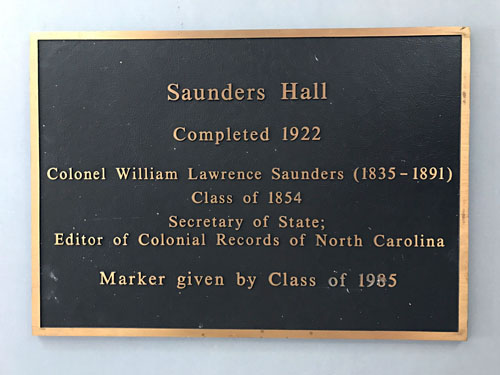

This month’s Artifact of the Month is the plaque that appeared on the building now known as Carolina Hall.

Completed in 1922, the academic building originally got its name from class of 1854 graduate William Lawrence Saunders. Leading into 2015, UNC students objected to Saunders’ reported membership in the Ku Klux Klan and issued a call to action. According to the News and Observer, the UNC Board of Trustees deliberated for “about a year,” eventually voting 10-3 to select a more “unifying name.”

Even before the Board’s deliberation, some students proposed that the building should honor anthropologist and writer Zora Neal Hurston. The students advocated for that name because as an African American woman, her identity contrasted the issues of racism and sexism perpetuated by having Saunders’ name on the building. Hurston also had ties to the University: in 1939 she attended writing classes at UNC with playwright Paul Green. Some activists used hashtags like “#HurstonHall” on Twitter, while others made T-shirts like this one, from the University Archives’ digital T-shirt archive.

On May 28, 2015, the UNC Board of Trustees proceeded with renaming Saunders Hall to Carolina Hall. The Board also issued a sixteen-year moratorium on renaming historic buildings. According to The Daily Tar Heel, some activists critiqued the moratorium as well as the selection of the name “Carolina Hall.”

In a May 2015 article of the Daily Tar Heel, senior Judy Robbins was quoted as saying, “Renaming it Carolina Hall is automatically silencing all of the students who worked on this and also all students of color who have ever attended UNC and ever will attend UNC.” Carolina Hall officially reopened in the fall of that same year with a new name plaque. The old Saunders Hall plaque came to the North Carolina Collection Gallery.

On November 11, 2016, a new exhibit opened exploring the history of the building’s name, William Saunders, and the Reconstruction era.