“An account of a particularly raucous election in [what was then] Dobbs County in March 1788 from New Bern’s North Carolina Gazette allows us to ‘see’ the scene at the courthouse in Kinston….The sheriff, election inspectors and clerks sat at a bench…. watching as the county’s 372 voters cast ballots [for ratifying-convention delegates] into a box….

“Balloting went on until sunset. As natural light waned, people lit candles…. The polls closed, and the sheriff began ‘calling out’ the ‘tickets’….

“One Federalist candidate, Colonel Benjamin Sheppard, seeing that he was going to lose… started verbally abusing the other candidates; then he threatened to beat one of the inspectors. Suddenly the Federalists — at least 12 or 15 of them — pulled out a set of clubs they had hidden and knocked or pulled down all the candle holders, throwing the hall into darkness. ‘Many blows with clubs were heard to pass,’ the Gazette reported, but most were said to land on fellow Federalists, since the Antifederalists, who came unprepared to defend themselves, fled for their lives. One blow, however, hit the sheriff. Then ‘the ticket box was violently taken away,’ which effectively ended the election with no official result….

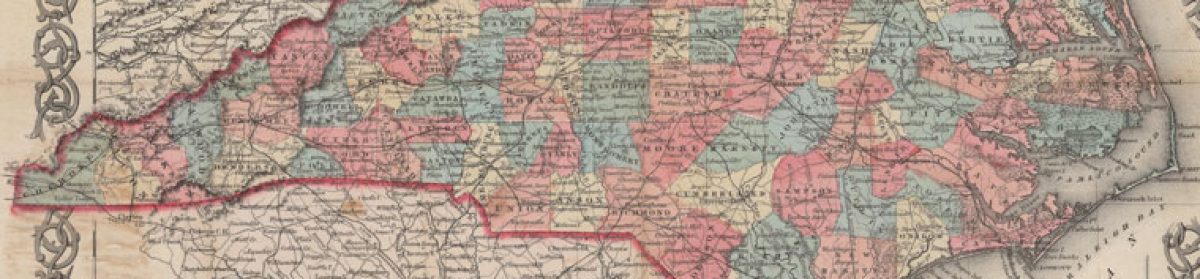

“Dobbs County would go unrepresented at the ratifying convention in Hillsborough.”

— “From Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788” by Pauline Maier (2010)