One way that a book can become rare is to be banned. Banned books – the Rare Book Collection, it has them! A week ago, Tuesday evening, as part of the University-wide First Amendment Day, the Rare Book Collection sponsored an evening where members of the University community read from banned and censored books in the original editions held by RBC. There was also a small one-night display of banned books including Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal (1857), the Olympia Press edition of Lolita (1955), and the Shakespeare and Company first edition of Ulysses (1922).

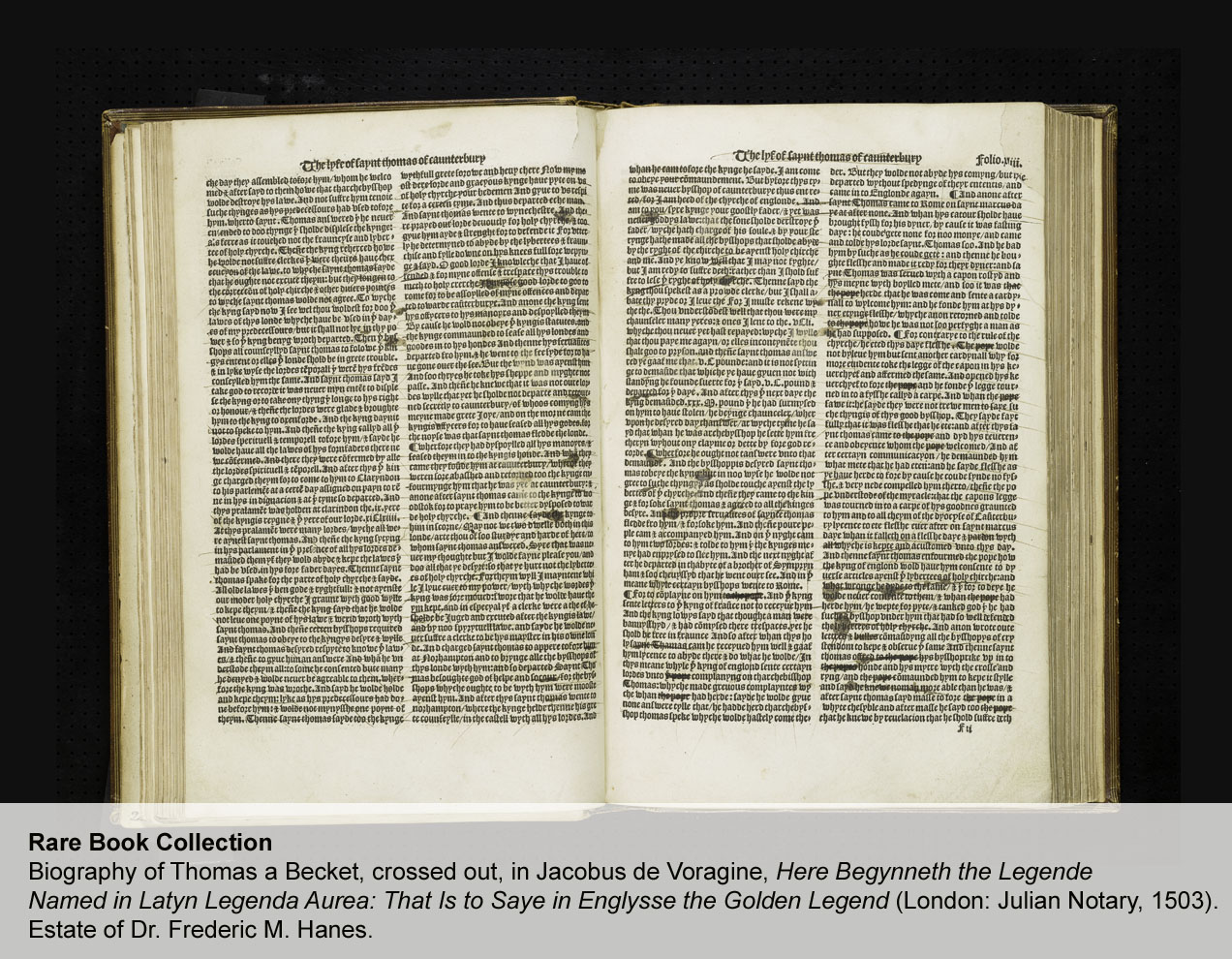

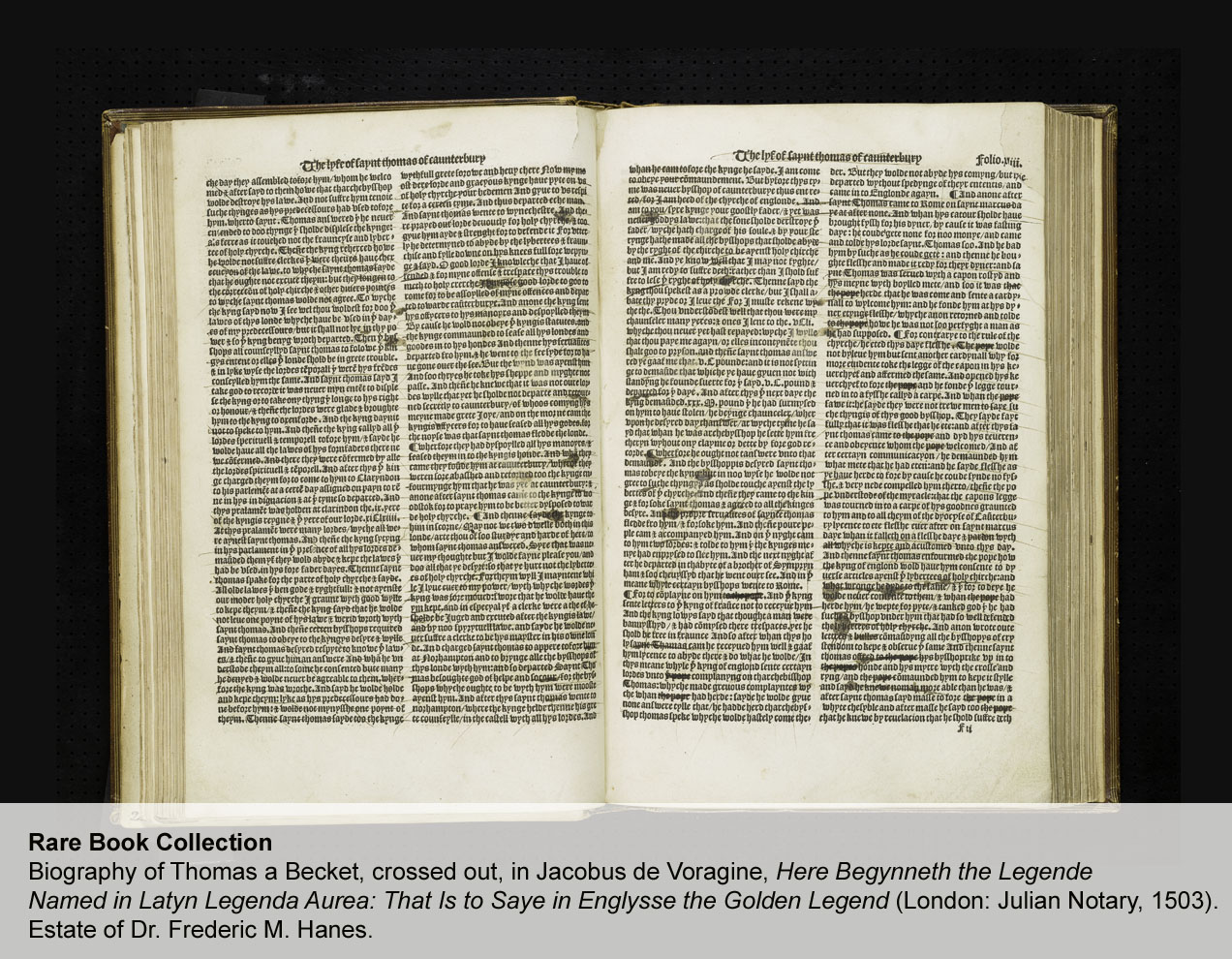

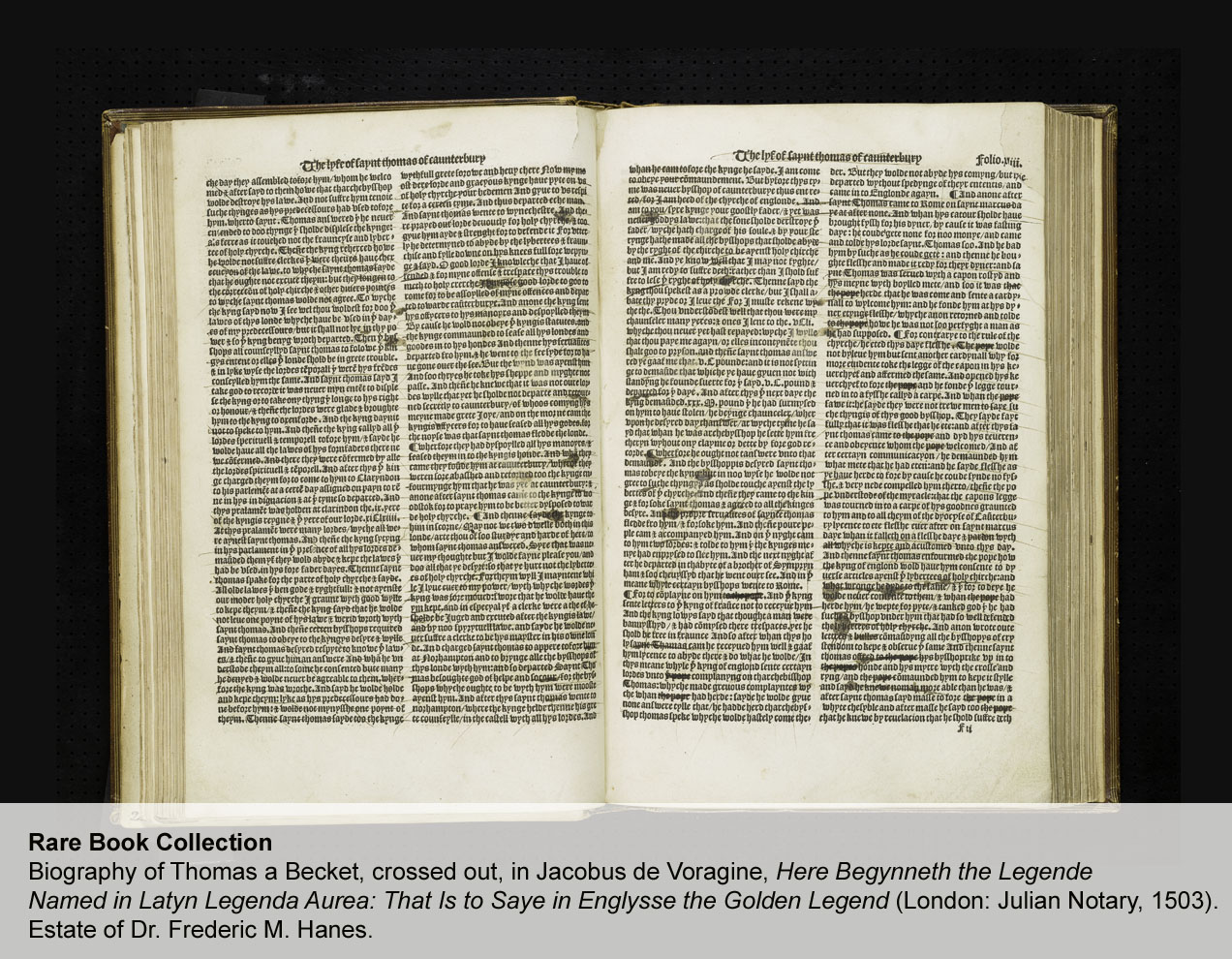

The earliest work read from was Voragine’s Golden Legend. RBC’s 1503 edition has the biography of Thomas Becket crossed through and the Pope’s name blotted out. As recently as a 2006 BBC poll, Becket was voted the second-most hated Briton – just behind Jack the Ripper! The censorship of the RBC copy probably took place in the 1530s.

Anne Steinberg, a graduate student in Romance Languages, read “Oppression” from Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie – first in her wonderful velvet-voiced native French, and then in English translation. University Librarian Sarah Michalak read the dramatic scene of Eliza’s crossing the ice from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (the book was burned in Atlanta). Poet Michael McFee read from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in the 1855 edition. And Juan Carlos González Espitia, associate professor of Romance Languages, gave us a passage on suicide, in the original Spanish as well as an English translation, from José María Vargas Vila’s Ibis.

First Amendment attorney Hugh Stevens (also chair of the Friends of the Library) read from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in Joyce’s Ulysses, as well as from Judge Woolsey’s landmark ruling that the book was not obscene. Although the RBC’s copy of the first edition – gift of James Patton (UNC A.B. 1948) and Mary Patton – was on display for the evening, Stevens read instead from the Egoist Press edition, printed eight months later. The copy had belonged to attorney Mangum Weeks (UNC A.B., 1915) and had an apt inscription referring to the inability of the book to travel through the U.S. mail.

Undergraduate English major Margaret Grady howled Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. And Kirill Tolpygo, Interim Librarian for Slavic & East European Resources & Curator of the André Savine Collection, ended the program with a brilliant passage from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s First Circle. He read it from the first Russian edition, and then in English translation from a paperback that had belonged to American writer Walker Percy.

It was an enthusiastic audience, with many undergraduate students being exposed to writers previously unknown to them. Indeed. Libraries exist to collect the historical record. We value the First Amendment!