To prepare for the Wilson Special Collection Library’s upcoming Hallowzine! event, I wanted to learn more about the history of zines to gain a better understanding of the historical and social contexts they evolved from. When I started my research, it seemed that without fail any website or article I found about zines would always begin by trying to answer one question: “What is a zine?” The answer is broad, and the content, style, and audience of zines vary widely, but there are several shared characteristics that make a zine:

- Zines are self-published or published by a small, independent publisher. Self-publishing allows marginalized voices to express themselves beyond the constraints of mainstream media, and also lets authors take control of the process of publishing. Zines also present an alternative to the hierarchical and commodified world of mainstream media.

- Zines are non-commercial, and are printed in small numbers, circulating only through specific networks. They are underground publications that tend to have niche audiences.

- Zines provide a vehicle for ideas, expression, and art. They build connections between people and within groups, and provide modes of communication in addition to information dissemination.

- There are exceptions to every rule, and though many have shared characteristics, there is no formal definition of a zine.

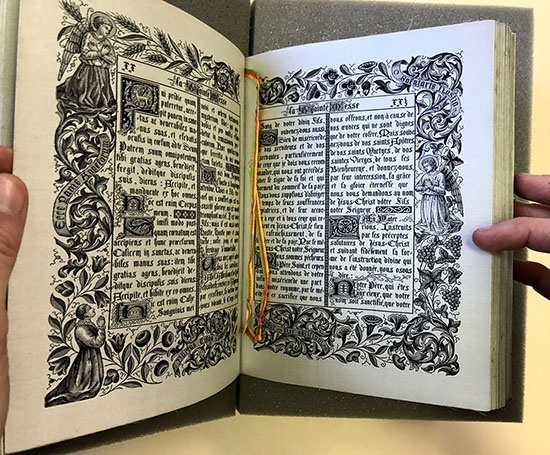

PN6777.A77 B65 2008

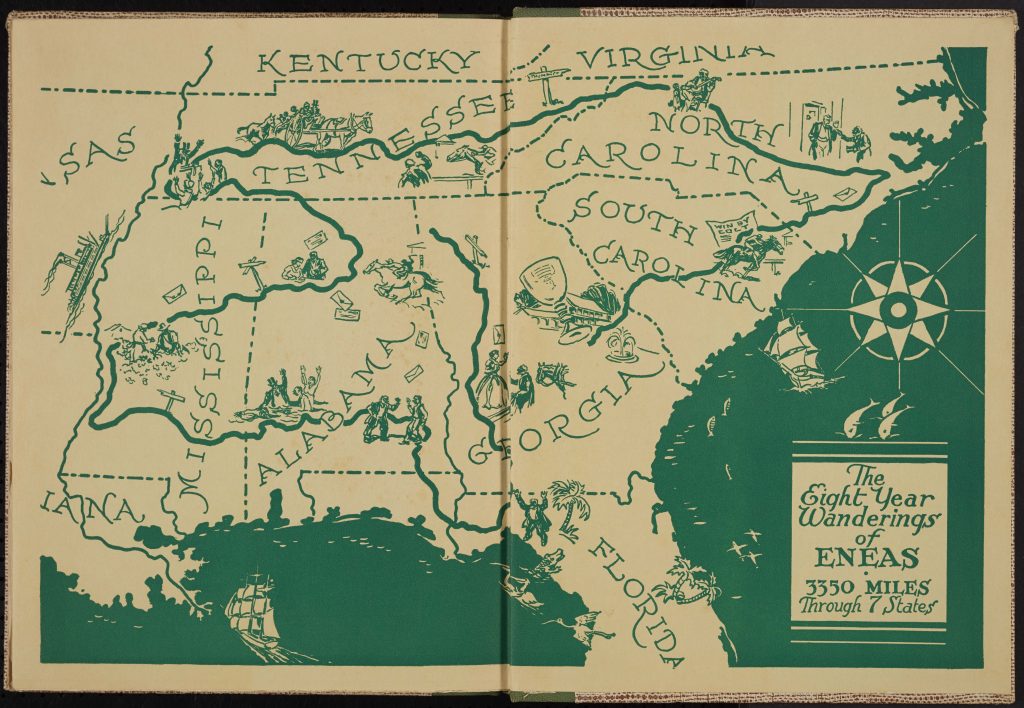

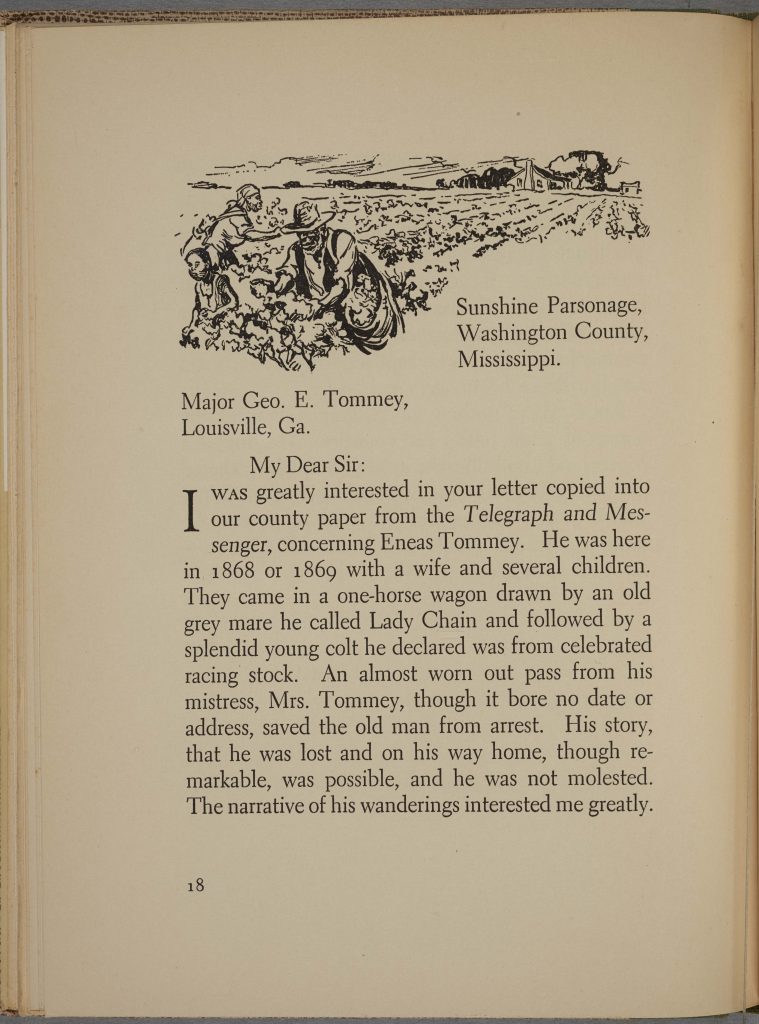

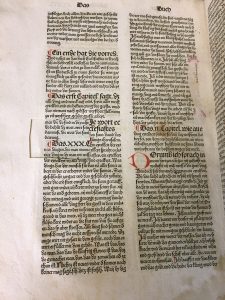

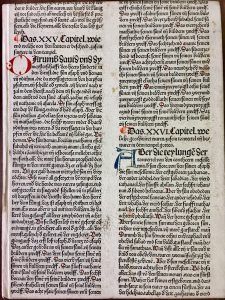

Zines were first created in the science fiction fandoms of the 1930s, taking their name from fanzine, which is short for “fan magazine.” Long before the advent of the Internet, zines allowed fans to create networks, share ideas and analyses, and collaborate on writing and artwork.

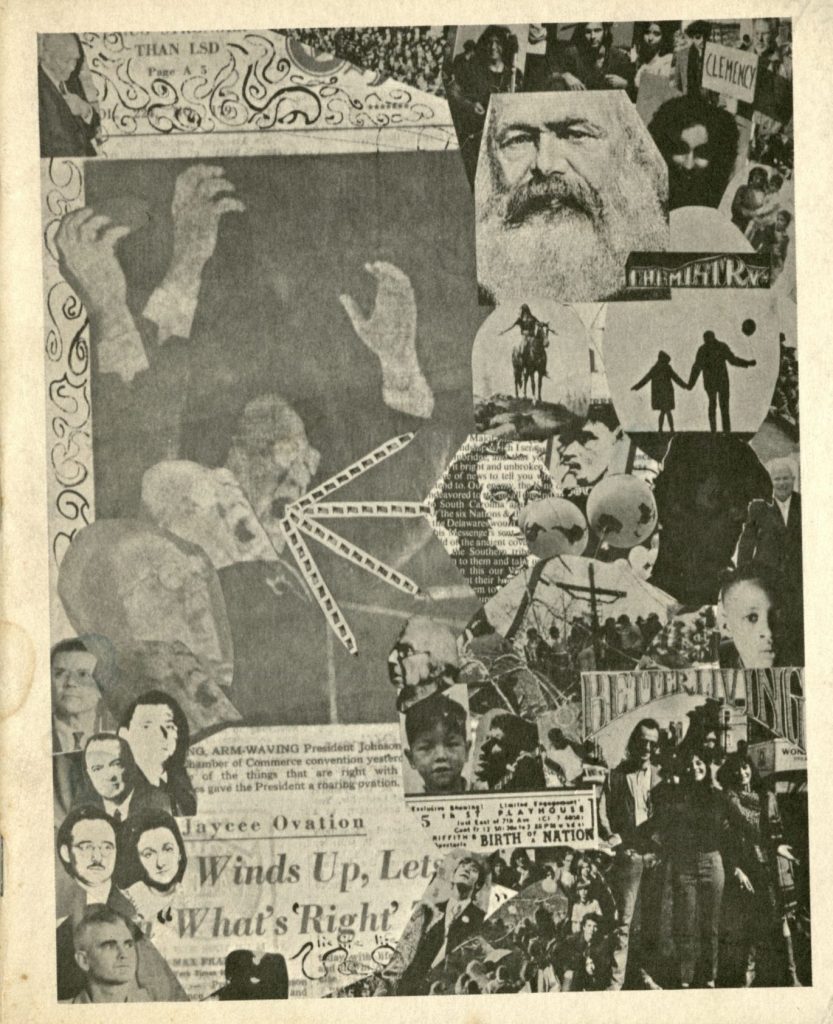

The counterculture movements associated with the Beat generation of the 1950s and 1960s saw a growth of the underground press, which played an important role in connecting the people across the US. Although the underground press often involved significantly more people and resources in the production of materials, it provided a function that became a key part of zine culture in the 1980s and beyond: giving people a voice outside the scope of the mainstream media.

Art and literary magazines of the 1960s and 1970s were based on a similar need to circumvent the commercial art world, and were printed cheaply and spread through small, niche networks. Many of them combined art, politics, culture, and activism into a single eclectic publication, redefining what a magazine could be, and influencing the rise of activist artists’ magazines that shaped the punk and feminist scenes later on.

The punk music scene of the 1980s expanded upon the self-published format by creating a wide of array of constantly evolving zines dedicated to the musical genre that were both fanzines and political tracts. Punk zines were more than just magazines–they represented the aesthetic and ideals of an entire subculture, a condensed version of this cultural revolt against authoritarianism.

Similarly subversive, the riot grrrl movement grew out of the punk subculture and developed a zine culture of its own, focusing on feminism, sex, and chaos. The Sallie Bingham collection at Duke University’s Rubenstein Library has a large selection of zines by women and girls created during this period. The collection’s website also provides a short description of the role of zines within the riot grrrl movement:

“In the 1990s, with the combination of the riot grrrl movement’s reaction against sexism in punk culture, the rise of third wave feminism and girl culture, and an increased interest in the do-it-yourself lifestyle, the women’s and grrrls’ zine culture began to thrive. Feminist practice emphasizes the sharing of personal experience as a community-building tool, and zines proved to be the perfect medium for reaching out to young women across the country in order to form the ‘revolution, girl style.'”

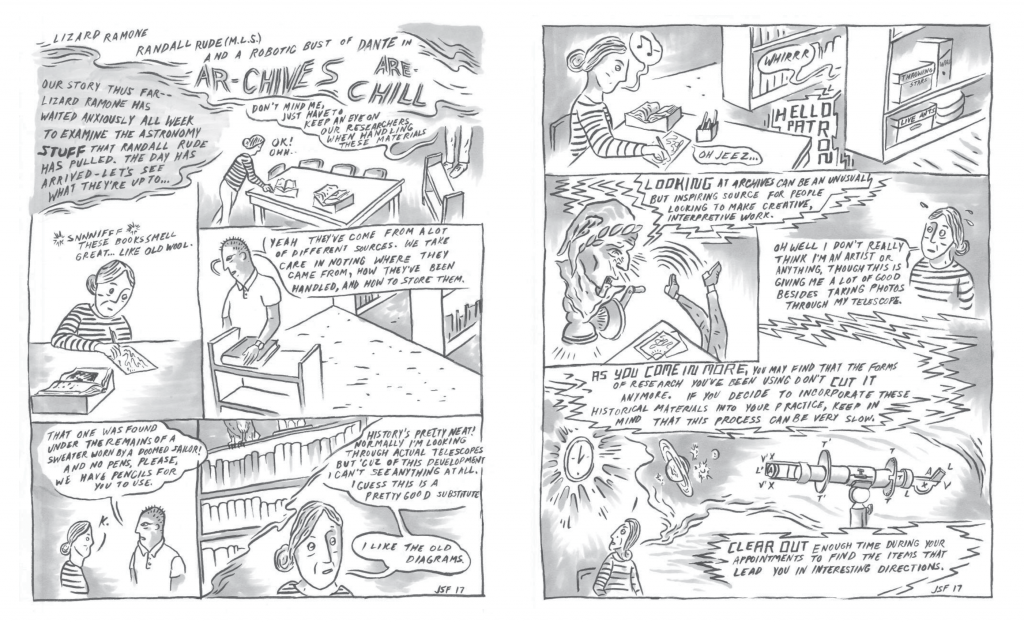

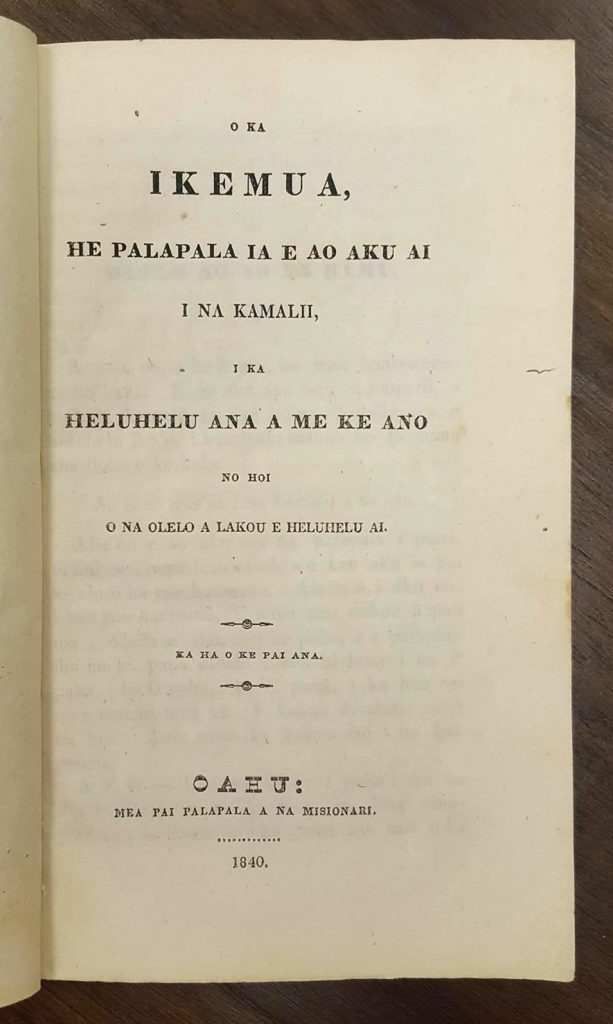

Examples of zines can be found at the Sloane Art Library as well as in the Rare Book Collection. Within the Rare Book Collection, zines comprise part of the Beats Collection, the Mexican Comic Collection, and the Latino Comic Collection. All three collections provide diverse examples of the genre.

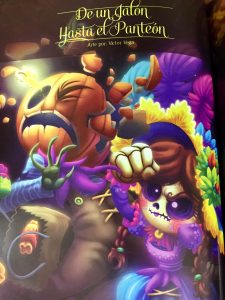

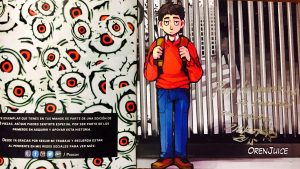

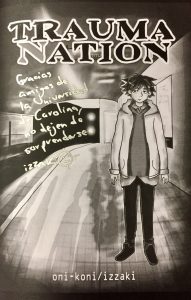

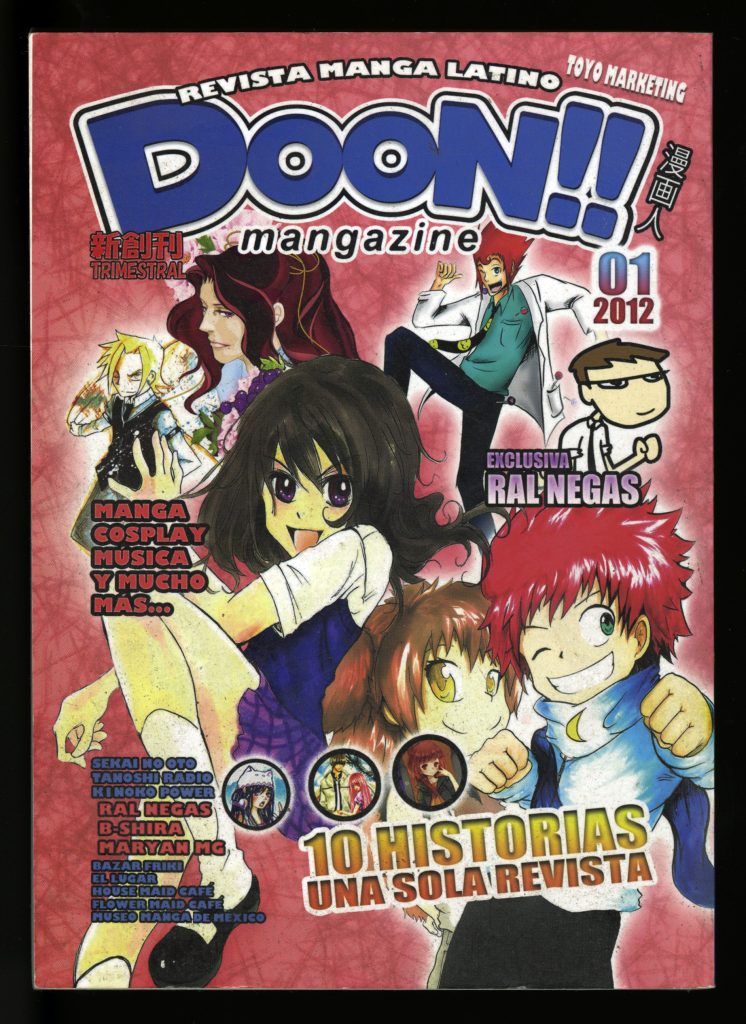

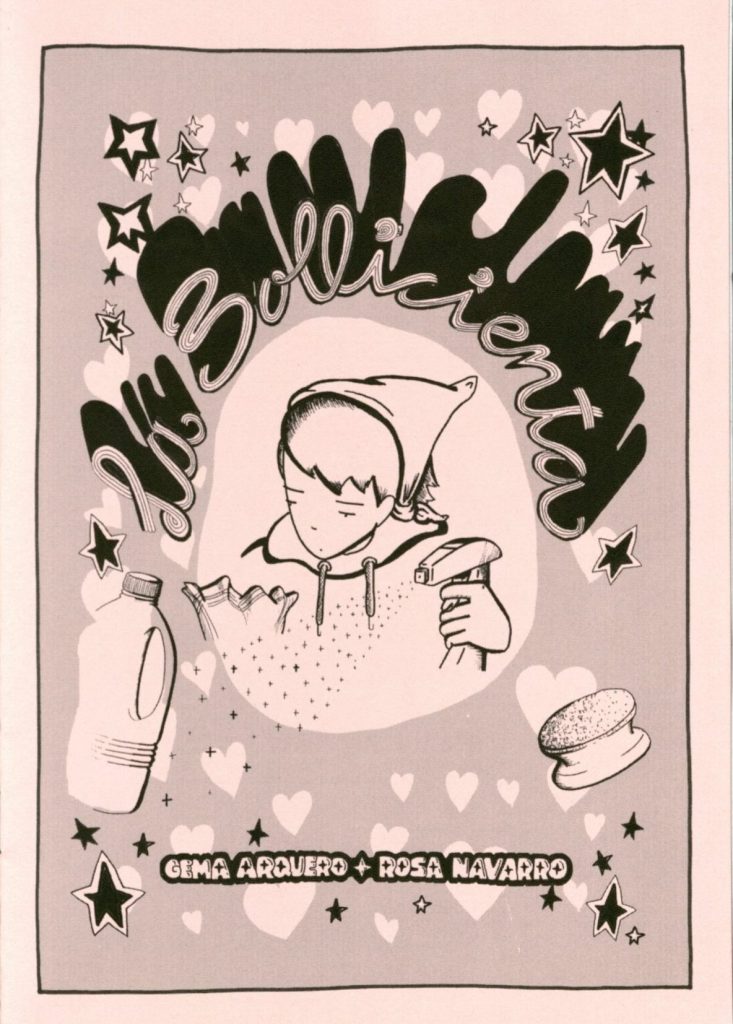

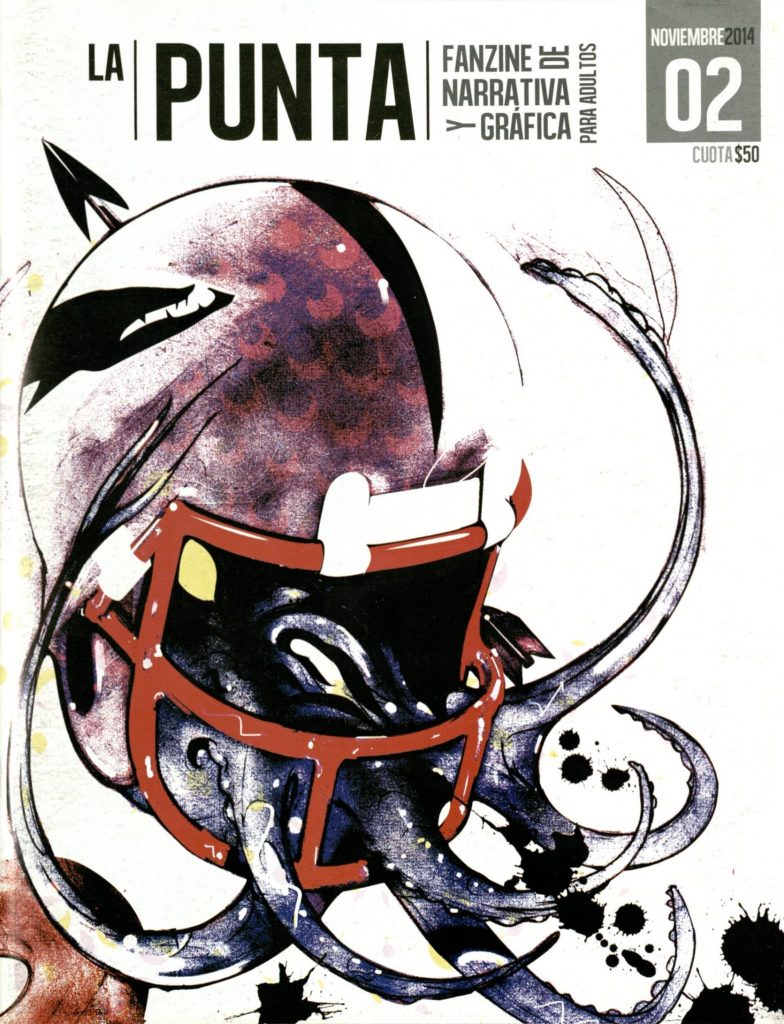

The Mexican Comic Collection, a collection of comic books and other graphic material produced in Mexico by Mexican writers and artists, contains examples of self-published artist zines and fanzines from the contemporary comic and graphic novel scene.

PN6790.M482 M4

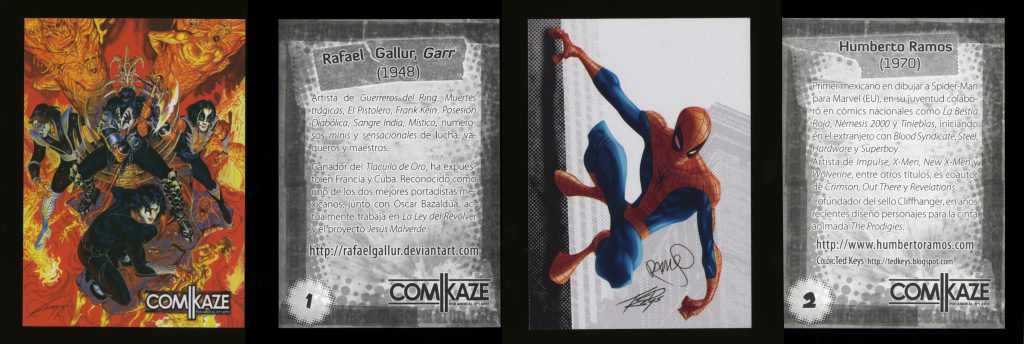

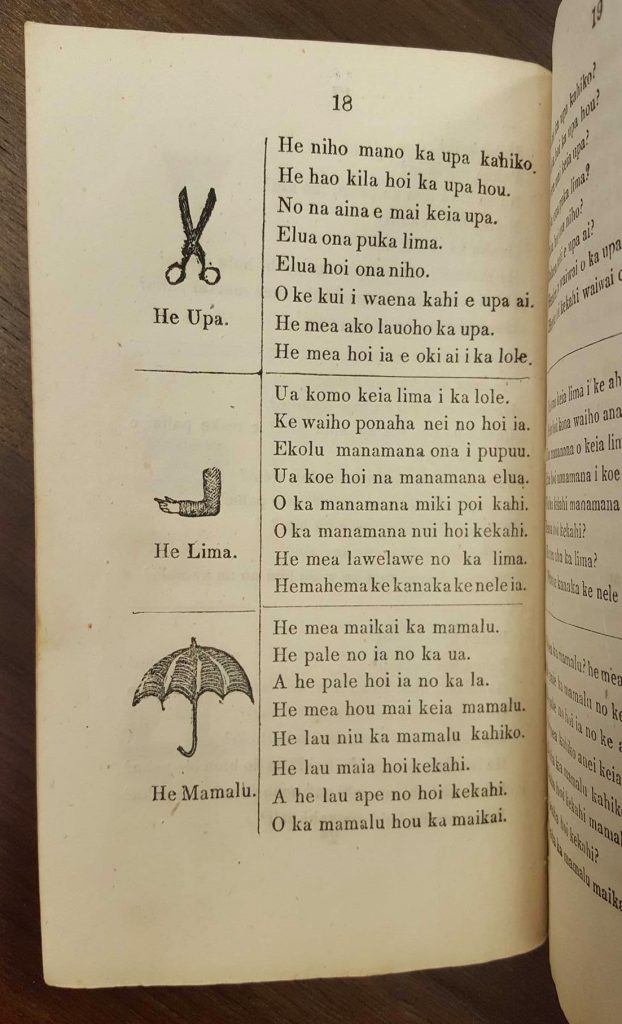

The Latino Comic Collection, a collection of comics and graphic material produced by contemporary US-born Latino artists and writers, also contains several examples of zines. Many of them are small, hand-drawn booklets, but others are more professionally produced.

PN6726.L38

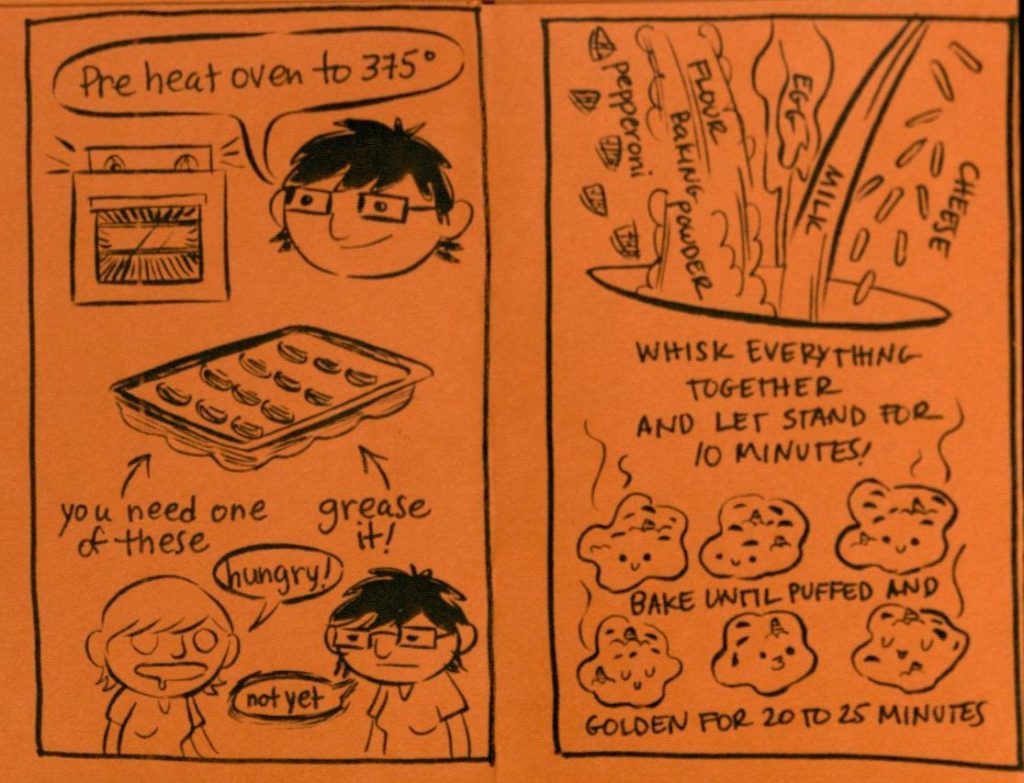

Pizza Puffs, a zine made to share one of the artist’s favorite recipes.

PN6726.L38

If you’re interested in learning more about zines, check out the Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library’s Sallie Bingham Collection at Duke University, which contains a robust collection of zines by women and girls. They also provide a resource page that is an excellent starting point for learning more about zines and their history.

And if you’re interested in making zines, please join us on October 31st from 1:00 pm – 4:00pm for Hallowzine!, a zine-making event at Wilson Library where you can learn more about zines and apply your DIY skills to making one of your own. A variety of zines from the Sloane Art Library’s collection will also be on display in Wilson Library during the event, so please stop by!