Item description: Letter, dated 3 April 1862, from Julian C. Ruffin to his wife Charlotte Ruffin. The letter describes Methodist prayer meetings; conflicts over the refusal of Quaker draftees to fight; and common amusements at Entrenched Camp. Ruffin also gives his wife advice on how to manage their plantation in his absence.

Item citation: From folder 15 of the Ruffin and Meade Family Papers #642, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

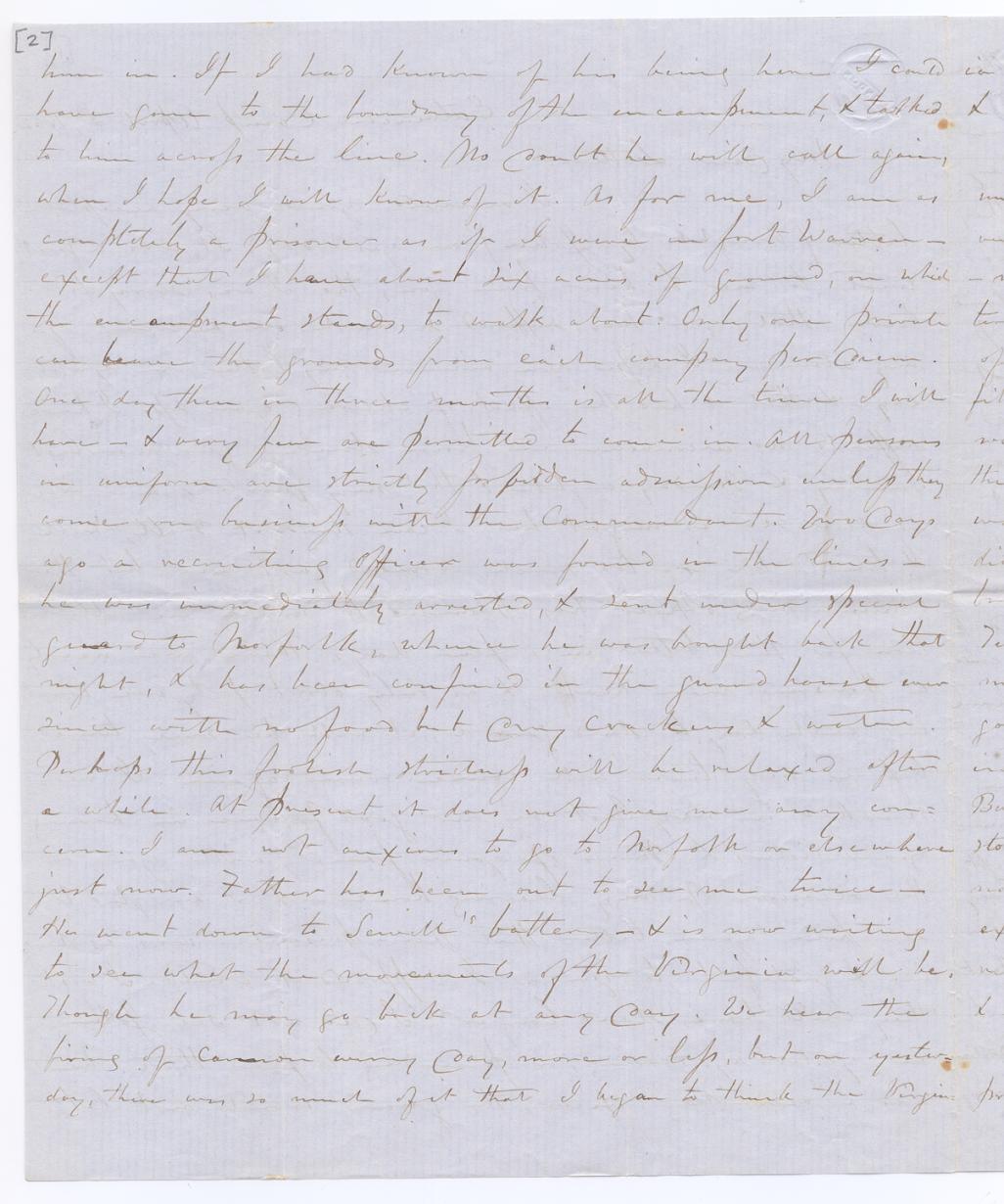

Item transcription:

Entrenched Camp, April 3d, 1862

My dear Lottie:

I received your very acceptable letter (brought by John) on yesterday. It was a great treat to me to hear from you, tho’ I was sorry to learn that you had suffered so much on account of my absence. I hope you received my letter on yesterday_ & that it had the effect of cheering you up. I have suffered no inconvenience from standing guard on last Sunday & Sunday night_ & tho’ my quarters were not as desirable as might be, I can stand it pretty well I trust. We are too much crowded just now, but the commanding officer has promised to make an alteration for the better in a few days. There are nearly a thousand men here, & as only about forty are wanting each day to stand guard, it will be some time before my turn will come round again. I remarked in my last on our good fortune in having your sisters & others of your family with you on the occasion of my leaving home_ & I am glad to see from your letter that their presence was as cheering & grateful to you as I supposed it would. I wish they could have staid longer. I did not see John on yesterday. Fearing, or pretending to fear that he was a recruiting officer, the guard would not let him in. If I had known of his being here I could have gone to the boundary of the encampment, & talked to him across the line. No doubt he will call again, when I hope I will know of it. As for me, I am as completely a prisoner as if I were in Fort Warren_ except that I have about six acres of ground, on which the encampment stands, to walk about. Only one private can leave the grounds from each company per diem. One day then in three months is all the time I will have_ & very few are permitted to come in. All persons in uniform are strictly forbidden admission unless they come on business with the Commandant. Two days ago a recruiting officer was found in the lines_ he was immediately arrested, & sent under special guard to Norfolk, whence he was brought back that night, & has been confined in the guard house ever since with no food but dry crackers & water. Perhaps this foolish strictness will be relaxed after a while. At present it does not give me any concern. I am not anxious to go to Norfolk or elsewhere just now. Father has been out to see me twice – he went down to Sewell’s battery – & is now waiting to see what the movements of the Virginia will be. Though he may go back at any day. We hear the firing of cannon every day, more or less, but on yesterday, there was so much of it that I began to think the Virginia had gone down. Such was not the case, however, & I fear she will not be ready for a week or more.

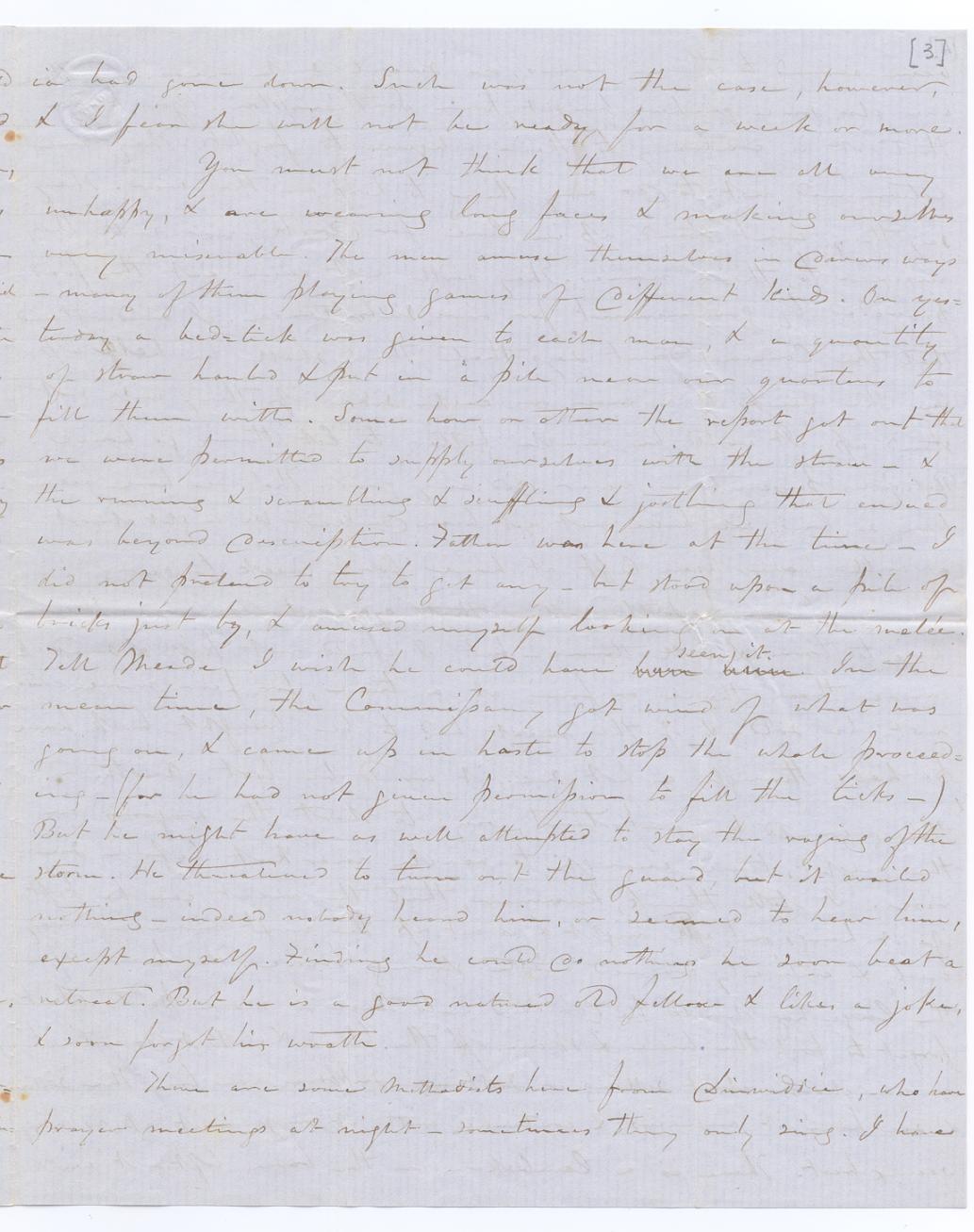

You must not think that we are all very unhappy, & are wearing long faces & making ourselves very miserable. The men amuse themselves in diverse ways – many of them playing games of different kinds. On yesterday a bed-tick was given to each man, & a quantity of straw hauled & put in a pile near our quarters to fill them with. Some how or other the report got out that we were permitted to supply ourselves with the straw_ & the running & scrambling & scuffling & jostling that ensued was beyond description. Father was here at the time. I did not pretend to try to get any_ but stood upon a pile of bricks just by, & amused myself looking on at the melee. Tell Meade I wish he could have seen it. In the mean time, the Commissary got wind of what was going on, & came up in haste to stop the whole proceeding_ (for he had not given permission to fill the ticks__) But he might have as well attempted to stay the raging of the storm. He threatened to turn out the guard, but it availed nothing_ indeed nobody heard him, or seemed to hear him, except myself. Finding he could do nothing he soon beat a retreat. But he is a good natured old fellow & likes a joke, & soon forgot his wrath.

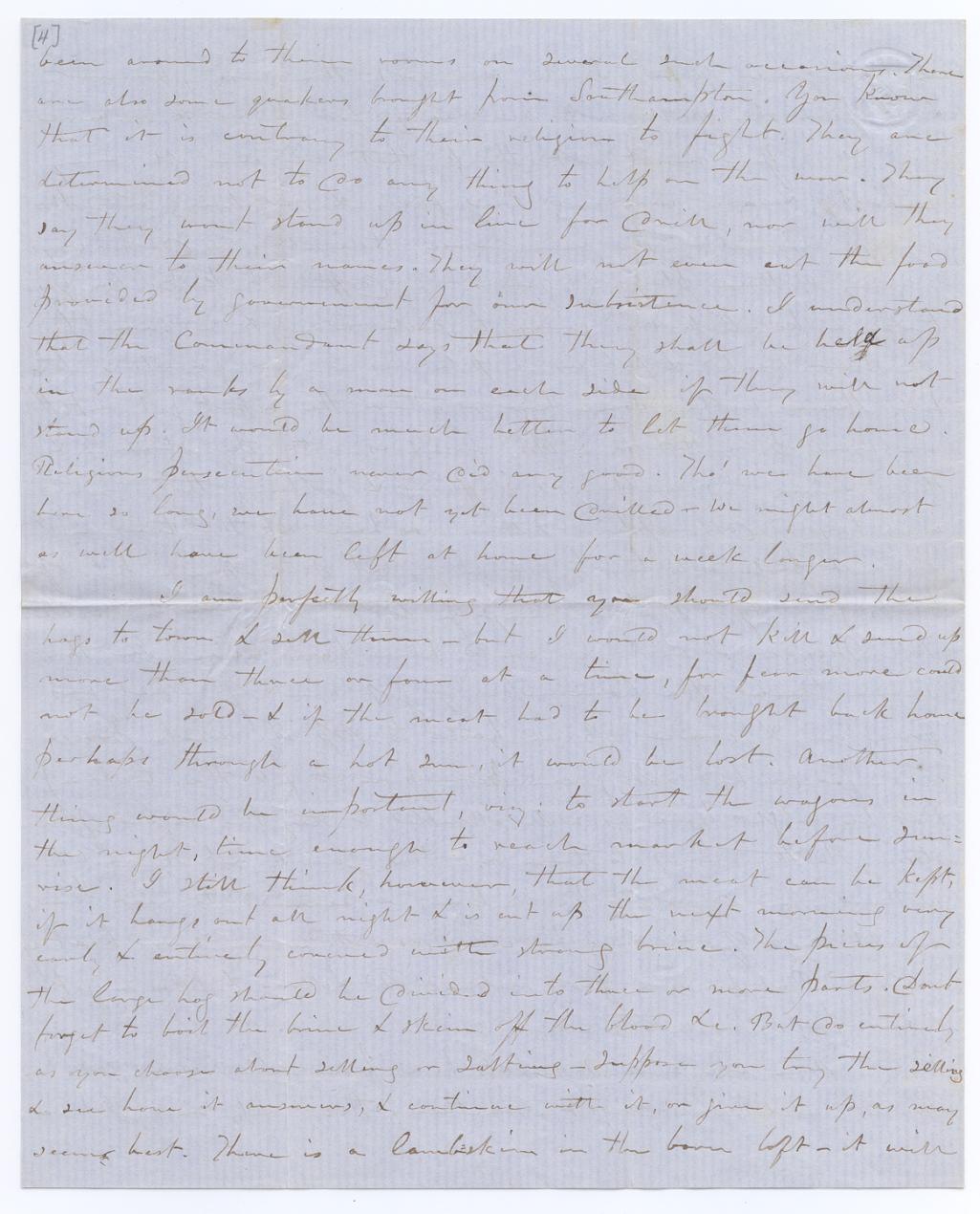

There are some Methodists here from Dinwiddie, who have prayer meetings at night_ sometimes they only sing. I have been around to their rooms on several such occassions. There are also some quakers brought from Southampton. You know that it is contrary to their religion to fight. They are determined not to do any thing to help on the war. They say they wont stand up in line for drill, nor will they answer to their names. They will not even cut the food provided by government for our subsistence. I understand that the Commandant says that they shall be held up in the ranks by a man on each side if they will not stand up. It would be much better to let them go home. Religious persecution never did any good. Tho’ we have been here so long, we have not yet been drilled_ we might almost as well have been left at home for a week longer.

I am perfectly willing that you should send the hogs to town & sell them_ but I would not kill & send up more than three or four at a time, for fear more could not be sold_ & if the meat had to be brought back home perhaps through a hot sun, it would be lost. Another thing would be important, viz: to start the wagons in the night, time enough to reach market before sunrise. I still think, however, that the meat can be kept if it hangs out all night & is cut up the next morning very early & entirely covered with strong brine. The pieces of the larger hog should be divided into three or more parts. Dont forget to boil the brine & skim off the blood &c. But do entirely as you choose about selling or salting – suppose you try the selling & see how it answers, & continue with it, or give it up, as may seem best. There is a lambskin in the barn loft_ it will furnish some wool_ make Lewis clip it off if you want it. I reckon you will want more salt, if you keep the pork. The sea salt is the cheapest.

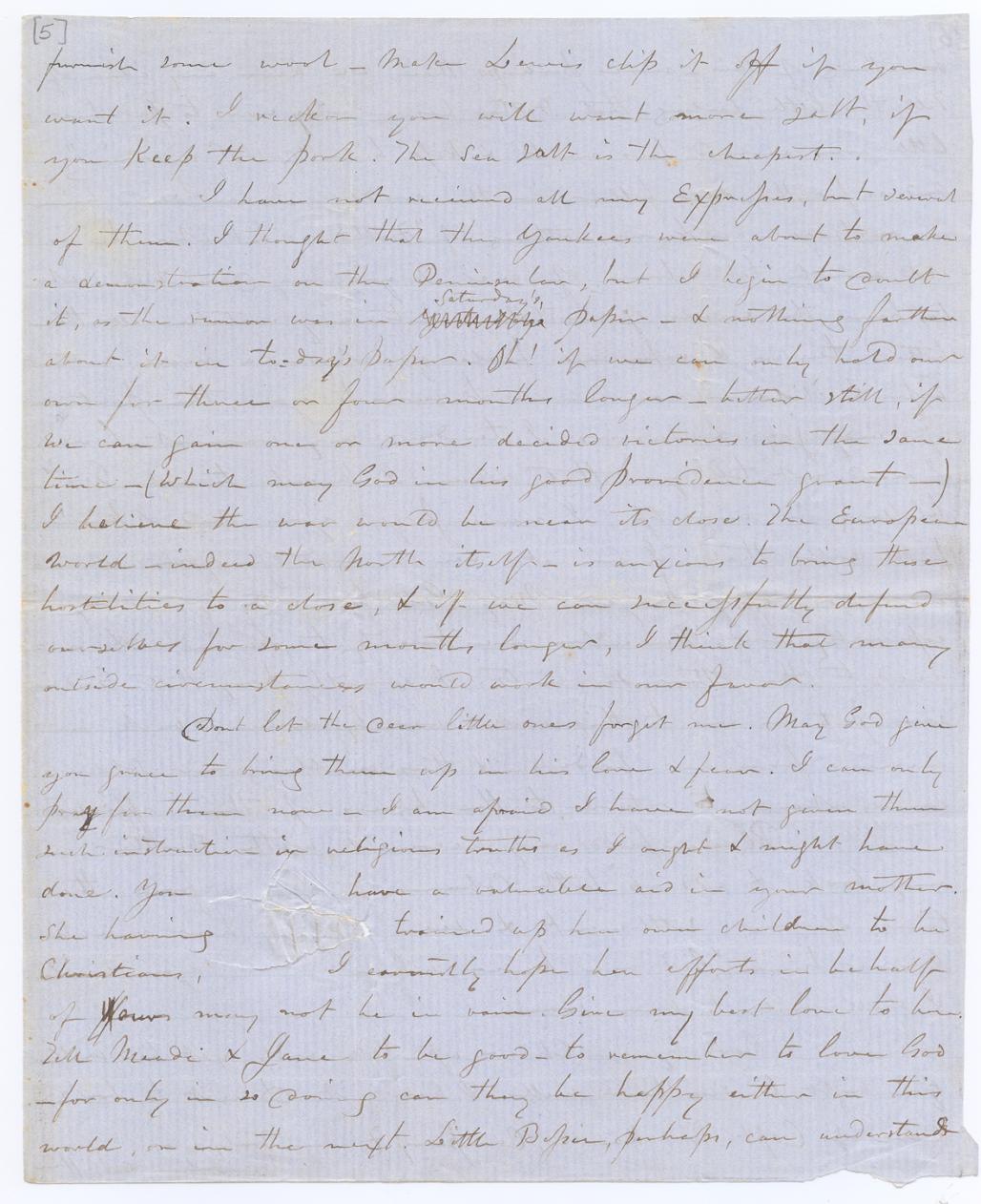

I have not received all my Expresses, but several of them. I thought that the Yankees were about to make a demonstration on the Peninsula, but I begin to doubt it, as the rumor was in Saturday’s paper_ & nothing farther about it in to-day’s paper. Oh! if we can only hold our own for three or four months longer_ better still, if we can gain one or more decided victories in the same time_ (which may God in his good providence grant_) I believe the war would be near its close. The European world_ indeed the North itself_ is anxious to bring these hostilities to a close, & if we can successfully defend ourselves for some months longer, I think that many outside circumstances would work in our favor.

Dont let the dear little ones forget me. May God give you grace to bring them up in his love & fear. I can only pray for them now_ I am afraid I have not given them such instruction in religious truths as I ought & might have done. You have a valuable aid in your mother. She having trained up her own children to be Christians. I certainly hope her efforts in behalf of ours may not be in vain. Give my best love to her. Tell Meade & Jane to be good_ to remember to love God_ for only in so doing can they be happy either in this world, or in the next. Little [Bessie?], perhaps, can understand something of this_ more perhaps than we have any idea of. Tell the little darling that Father has nobody now to put his little arm around his neck & kiss him “good morning”. And as for the dear fellow in the cradle_ I can send him no message_ he knows nothing of “Father”_ but when he is old enough tell him of me. To you, my dear wife, who has been the means of instilling into my nature all these better, tender & [unfinishing?] feelings, which a man without wife & children can never know_ to you, the partner of my joys & sorrows I tender my warmest love. I need not tell you that when I kneel to ask God’s blessing on myself, I never forget you. And I know full well that I am also remembered of you whenever you offer prayer. May God be with you always_ especially now. Remember me kindly to Lucinda_ & indeed to the other servants. I earnestly pray that God may soon put an end to this wicked war by driving back our enemies from our borders_ & thus enabling our soldiers every where to return to the homes of their affection.

Please find my account with Brother in my book, & add up both columns, from the time of our settlement, & see how much I owe him, & let me know when you write. I shall write to him soon.

Good-bye_ Cheer up_ all will yet be well. You ought to see how well I hear it. Direct to box 273, care of Capt. Brockwell, Company F.__

Truly yrs,

Julian C. Ruffin