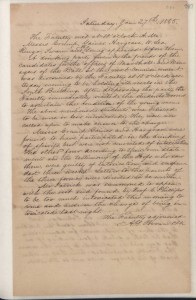

On the night of August 13, 1850, Charles Phillips, then a tutor of mathematics, heard “loud vociferations, high words, as of persons quarrelling, and other noises” coming from Old West (then known as West Building). As he went to investigate the disturbance, he could not have anticipated that the evening would end with him and a colleague cornered in a dorm room, fending off rioting students.

In his first sweep of West Building, Phillips found most of the students quiet in their rooms, but heard and saw students yelling and throwing stones at each other outside. He ran into his colleague Dr. Elisha Mitchell in the hallway, and they continued the investigation. In one room, the professors found “great disorder—the beds rumbled, the chairs in confusion, the floor very wet, and the remains of a stone vessel scattered up on it.” They found a nearly empty jug of whisky under the bed.

Upon leaving West, the professors encountered Manuel Fetter, professor of Greek language and literature, and retreated to the Laboratory to discuss the situation. However, as they left the Laboratory, they were immediately attacked. Phillips recalled:

Because of the vollies of stones which swept the passage I kept close to its northern wall, and looking through the opening that leads to the front door of the building I noticed a group of persons standing before the door. Immediately a volley of stones (or bats) entered, and a person passed me quickly accompanied by another volley. On speaking to him, I recognized Prof. Fetter who told me that he had been violently struck on the hand and leg. So violent was one of the blows that his cane was knocked to a distance from his hand.

When they eventually made their way back to West Building, they were met by more rowdy students, some disguised with blankets or fencing masks. As some students escaped through the windows, others began lobbing stones and sticks at the professors. The professors barricaded themselves in a student’s room, but the rioters continued their attack, knocking out a panel of the door. Phillips explained:

Discovering our exact position [in the room], those outside endeavoured to hit us by throwing obliquely into the room through the door and windows, and by introducing their hands so as to throw sideways directly at us. One individual introduced through a window, a stick two or three feet long and of the size of one’s wrist, evidently intending to swing it around and so strike us. As missiles were still entering the room, and our present was the only safe position, I immediately seized a chair and as an act of self defence urgently necessary, threw it in the direction of the concealed assailant. This act rendered the students outside much more excited, and threats of great violence, even to the getting our heart’s blood, were uttered for our striking a student.

After about an hour, a student, J.J. Slade, was able to reason with the rioters and escort the professors out on the condition that they leave campus immediately. The professors left and reported the night’s events to the president. They returned later that night with several other faculty members and searched the residence halls, but the disorder had subsided and most students were asleep in their beds.

The student who had come through the window with a club (and subsequently been hit by a chair) was expelled, but most students involved in the riot were not identified.

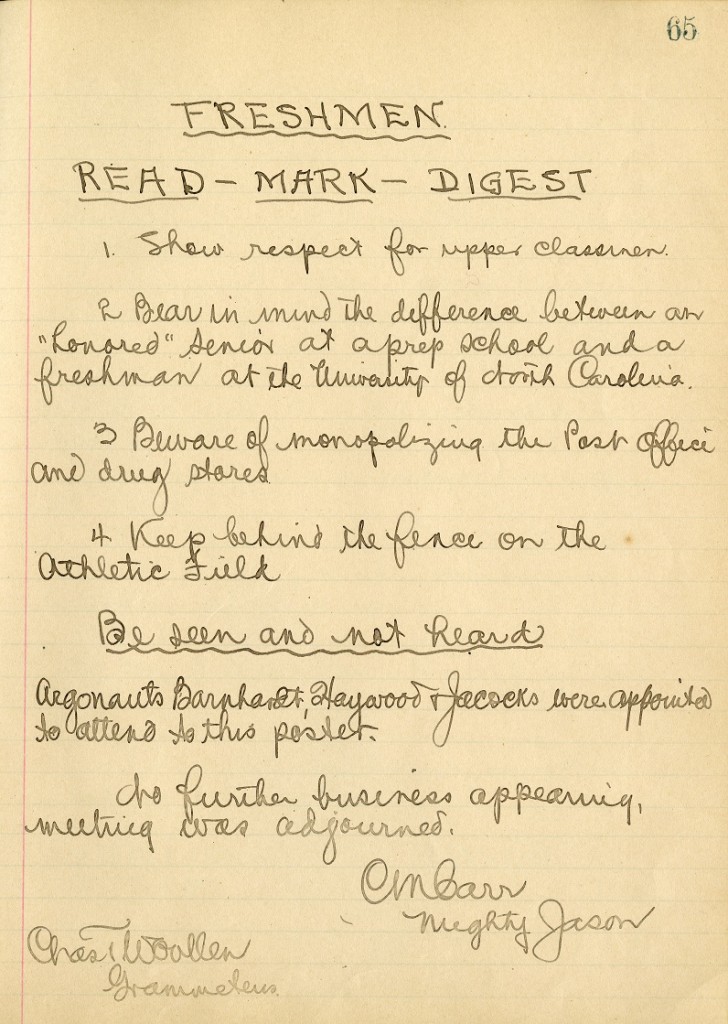

Charles Phillips’ testimony on the events of August 13, 1850

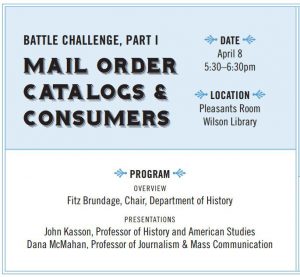

This Wednesday, Wilson Library and the UNC Department of History are putting on the first of two events that are 100 years in the making.

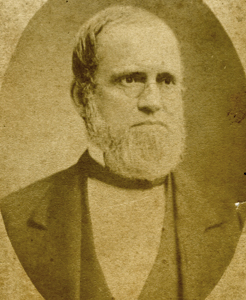

This Wednesday, Wilson Library and the UNC Department of History are putting on the first of two events that are 100 years in the making.![Kemp Plummer Battle [From the 1919 Yackety Yack, North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/uarms/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/03/kpb-194x300.jpg)