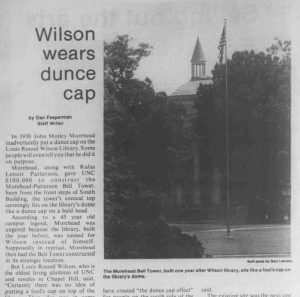

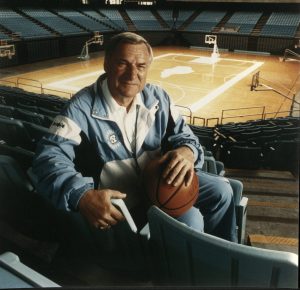

This mid 20th century photo shows the dunce cap effect of the Bell Tower on Wilson Library when viewed from South Building. UNC Image Collection, NC Collection Photo Archives.

Have you heard the story that the Bell Tower was intentionally placed right behind Wilson Library so that, when viewed from South Building, the top of the tower looks like a dunce cap on the round dome of the library?

The dunce cap story has been one of the enduring campus legends for decades. The story originally told was that John Motley Morehead, angered that Louis Round Wilson wouldn’t let him put the tower on top of the new library building, put it right behind to make fun of Wilson. I’ve heard a slightly different version on campus recently, which attributes it to an ongoing battle between two of the university’s “founding families,” the Moreheads and the Wilsons, making them seem like UNC’s version of the Hatfields and McCoys.

As with many campus legends, this one is not true, though some of the stories hint at what really happened.

The Bell Tower was the idea of John Motley Morehead, the Carolina alumnus and industrialist who donated the Morehead Planetarium and established the Morehead scholarships. According to Louis Round Wilson, Morehead’s first proposal was made during the renovation of South Building in the 1920s. Morehead, who had been interested in bringing a tower with chimes to the campus, suggested funding the construction of a tower on top of South Building under the condition that it be renamed the Morehead Building. The Trustees refused, and Morehead looked for other sites.

Morehead turned his attention to the new library building planned for the opposite end of Polk Place, and suggested a bell tower on top of it. This was indeed rejected by librarian Louis Round Wilson. Wilson spoke from his knowledge of bell towers on top of buildings at Cornell University and the University of Illinois. He wrote that, while pleasing to the campus in general, “the ringing of bells and chimes immediately above the reading rooms of the libraries in working hours played havoc with mental concentration and quiet study.”

Morehead had yet another idea: when the university announced a plan to move the large flagpole on campus from McCorkle Place to its current location in the center of Polk Place, Morehead suggested this as the perfect site for the bell tower. The flagpole could be placed on top.

Finally, by 1930, a location was settled. Though initially appearing to be at the very southern end of the campus, long-range plans to expand the university to the south would put the bell tower at the center of the campus, which is where it stands today. The Morehead-Patterson Memorial Bell Tower was dedicated on Thanksgiving Day, 1931.

It’s not clear when the dunce cap story began. The earliest published reference to it that I could find was in a 1975 Daily Tar Heel article. The author of the story, Dan Fesperman, had the advantage at the time of being able to go straight to one of the sources: 99-year-old Louis Round Wilson was still living in Chapel Hill. Wilson reviewed the debate over the placement of the tower and then addressed the legend directly. “When Wilson was asked if there was even a speck of truth in the Bell Tower legend, he said, ‘It wasn’t designed for that purpose at all.’ He then added, ‘But it does look that way – like a fool’s cap.”

Sources: “The Saga of the Morehead Patterson Bell Tower.” In Louis Round Wilson’s Historical Sketches. Durham: Moore Publishing Co., 1976. https://catalog.lib.unc.edu/catalog/UNCb1408393

Daily Tar Heel, 25 August 1975. http://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1975-08-25/ed-1/seq-44/