James Kern Kyser, better known as Kay Kyser, the “Ol’ Professor” of the popular radio program of the late 1930s and 40s, the “Kollege of Musical Knowledge,” retired and returned to his alma mater UNC-Chapel Hill in 1951 and started a second career. Earlier this week, on June 18th, 2019, Kyser would have turned 114. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard briefly looks back at both of his storied careers.

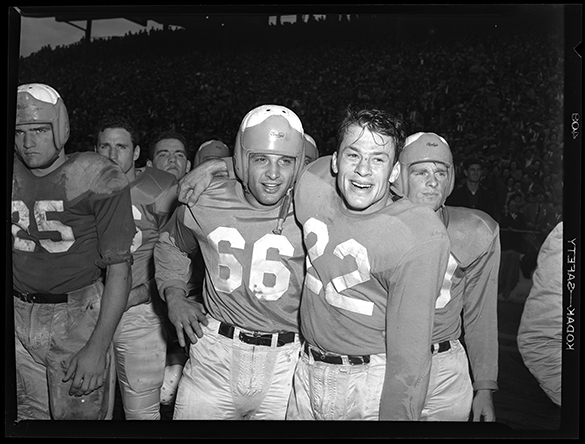

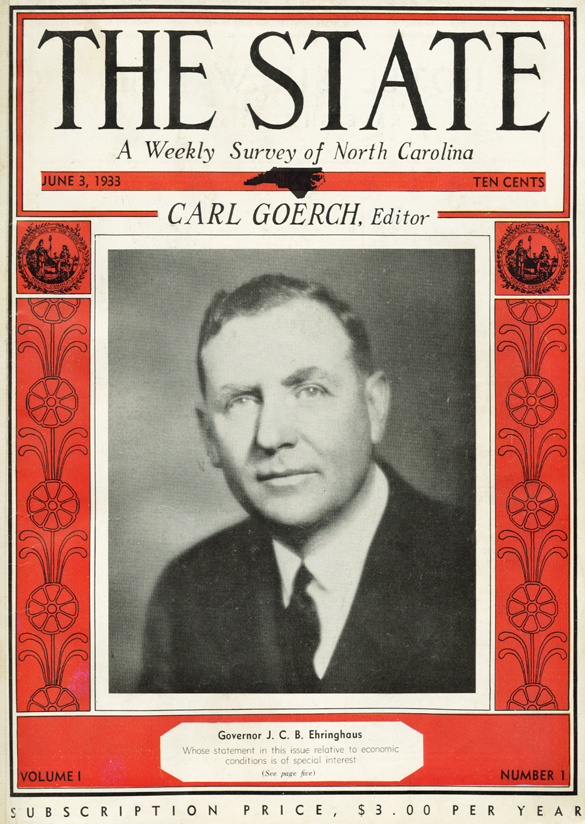

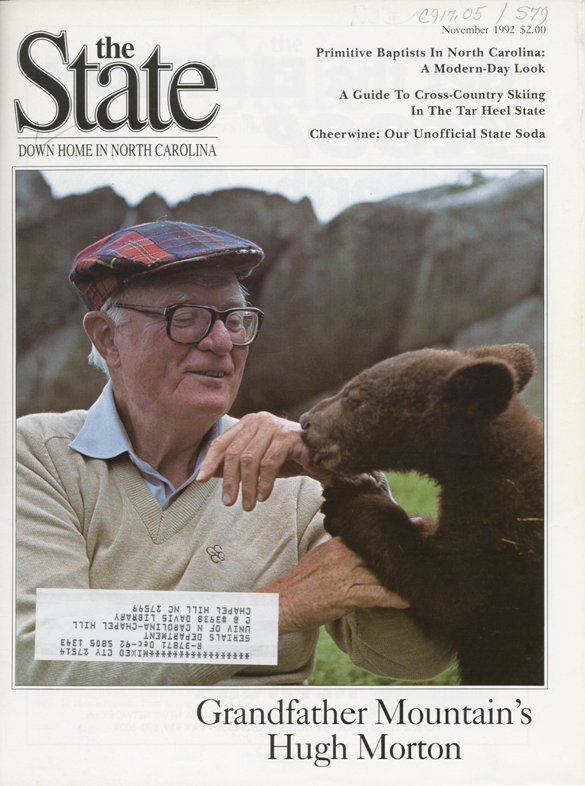

Hugh Morton (left) with Kay and Georgia Kyser during the 1951 Short Course in Press Photography, probably during the Saturday evening banquet at the Carolina Inn, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The negative is in the Morton collection, but the photographer is unknown and the date is determined by the published photograph of the Kysers seen below.

Soon after his retiring return to Chapel Hill, Kay Kyser picked up where he left off on stage with far less fanfare but as a true friend to his native North Carolina. On April 14, 1951, Kyser, along with his wife Georgia, joined his friend Hugh Morton at the second annual Southern Short Course in Press Photography banquet.

Photograph clipped from the front page of The Statesville Daily Record, Wednesday, April 18, 1951. The clipping depicts the Kysers as they examine a prize-winning photograph by Max Thorpe during the Southern Short Course on Press Photography banquet, held the previous Saturday, April 14.

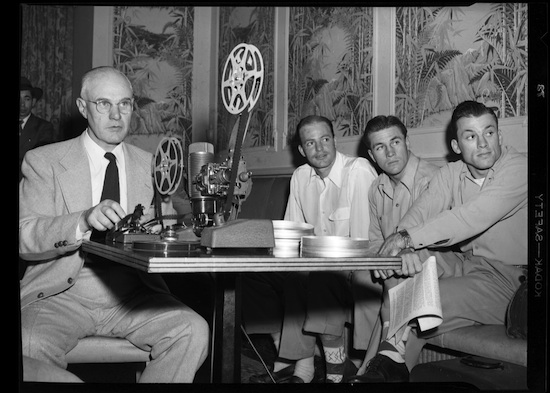

Editor’s note: Kyser made an appearance at another short course banquet, probably 1952, seen below. The two scans from negatives shown here are the only photographs of Kay Kyser in the collection. Neither appear to have been made by Morton unless he used a long cable release and triggered the exposure from a distance. The photograph below probably dates from the April 1952 short course because Morton’s photograph of “Happy John”—likely made in 1951—can be seen in the upper right corner of the photographs on display.

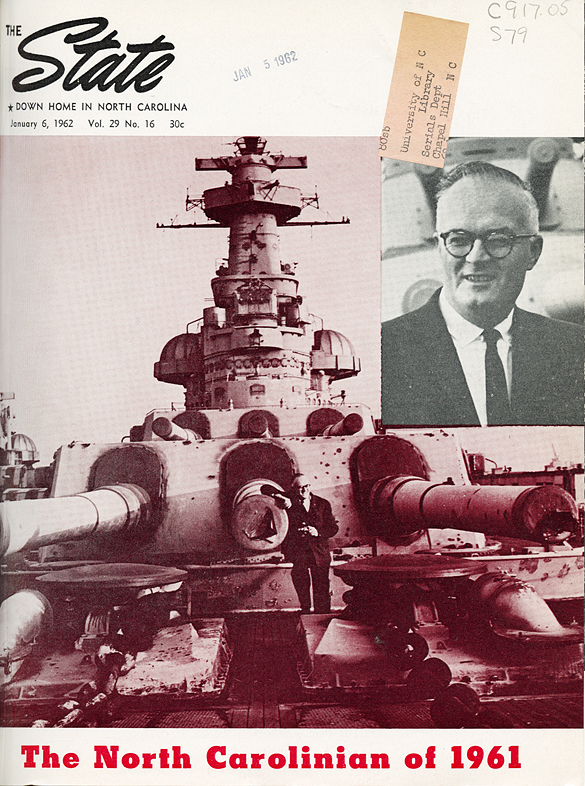

This negative in the Morton collection had an extensive caption written on the original negative envelope: “Kay Kyser and Billy Arthur are having fun kidding each other at the Southern Short Course In Press Photography in Chapel Hill as Norman Cordon and Beatrice Cobb look on. Kay Kyser and Billy Arthur were both former Head Cheerleaders at UNC, and both are standing (Billy Arthur’s height is about 3 feet 6). Kyser was so much a celebrity and so recognizable when wearing his trademark horn rimmed glasses that he often did not wear the glasses in order to retain his privacy in Chapel Hill. Norman Cordon was a famous Metropolitan Opera star, and Beatrice Cobb was Publisher of the Morganton News-Herald and Secretary of the North Carolina Press Association. Billy Arthur was a newspaper Publisher at Jacksonville, N.C., and later worked for the Chapel Hill paper, and he was also a press photographer.”

Kyser’s participation in the photographic short course was just one example of his many contributions to his native state following his long career in show business. His enthusiasm, energy, and dedication were the prime forces for WUNC-TV to get on the air in January of 1955. His faith and his dedication to the Christian Science Church became his passion. From his office on Franklin Street, Kyser became the producer-director of the film broadcasting department of the Christian Science Church.

Another Editor’s Note: While preparing Jack’s post and researching the Southern Short Course in Press Photography for an upcoming post, I encountered another Kyser contribution: a film titled, Dare: The Birthplace of America, produced by the University of North Carolina with its debut in May 1952. In a promotional news article printed in advance of the movie’s launch, playwright Paul Green wrote, “And anonymously behind [the film] was the imaginative dynamic of that gifted and devoted North Carolina citizen—Kay Kyser.”

The boy from Rocky Mount became one of the most famous faces of the swing era.

When James K. Kyser entered the University of North Carolina in 1923, his parents, both of whom were pharmacists, thought he would be a lawyer. But he had other ideas. He switched his major to economics because, according to Kyser, “the legal profession meant lots of work.”

Being selected a Carolina cheerleader gave him the opportunity to “perform.” He enjoyed riding around campus in a Model T Ford with the word “Passion” painted on its side. He excelled not only in academics, but he also excelled in extracurricular activities. He acted in Carolina Playmaker productions, was a Sigma Nu fraternity member, and was a member Alpha Kappa Psi, Order of the Grail, and the Golden Fleece honor societies. Because of his popularity on campus, he would, in 1926, inherit the job of leadership of the UNC campus band; although he couldn’t read music and he played no musical instrument. In addition, he was senior class president in 1928.

After graduation, he took the band on the road, but it didn’t really take off until the mid-1930s when he hired singer Ginny Simms and cornet player Ish Kabbible (his real name Merwyn Bogue). But when it did take off, it was in a league of its own.

Kyser was featured in several Hollywood movies. His first was That’s Right—You’re Wrong in 1939 with Lucille Ball; the last was Carolina Blues in 1944. He was often joined by such stars as Milton Berle, Dorothy Lamour, and Rudy Vallee.

He was called “The Ol’ Professor,” and he wore a short academic robe complete with mortarboard and tassel. He loved to clown-around with cornet player Ish Kabibble, plus he did a bit of dancing. At the top of his career, Kay Kyser’s band scored 35 top-ten hits, and appeared in Hollywood and New York. He played to 60,000 during one week at New York’s Roxy Theater.

The boy from Rocky Mount became one of the most famous faces of the swing era.

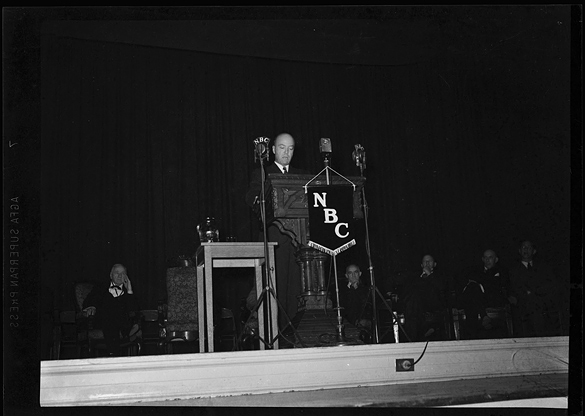

During the Depression and throughout World War II, Kyser offered his zaniness as a cure for adversity. At 9:30 on Wednesday nights, more than twenty million Americans would turn their radios to the NBC Red Network to hear Kay Kyser say, “Now we’re gonna have a little syncopation, so I want you to toddle out here and truck around the totem pole and sashay around the stage. What I mean is, C’mon, chillun. Le’s dance!”

Kyser also performed for thousands of World War II soldiers, feeling guilty that so many were marching off to their deaths while he was making big money. In a 1981 interview with Greensboro Daily News reporter Jim Jenkins, Kyser recalled being on a hillside in the Pacific Theater in the summer of 1945. “Countless thousands of GIs were sitting on these banks, and we could hear the firing in the background. They’d come up to you after and wring your hand, thanking you, completely oblivious to the fact that they were offering their lives so we civilians would have a good go at home. I thought, my, if that isn’t the ultimate of humility . . . I knew right then I’d never play another theater for money.”

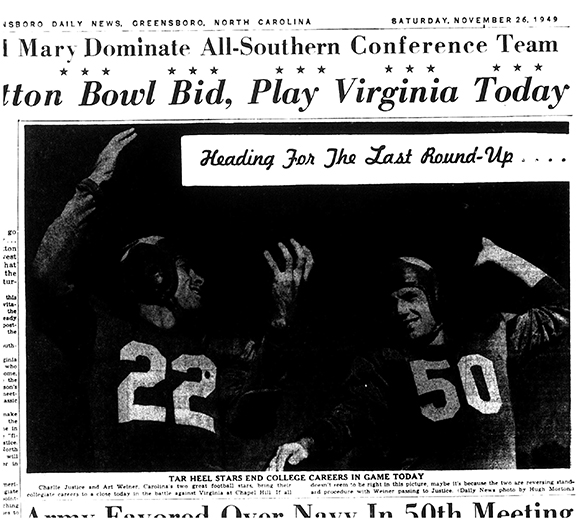

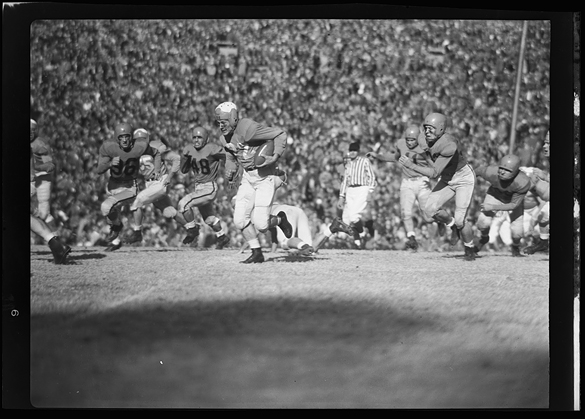

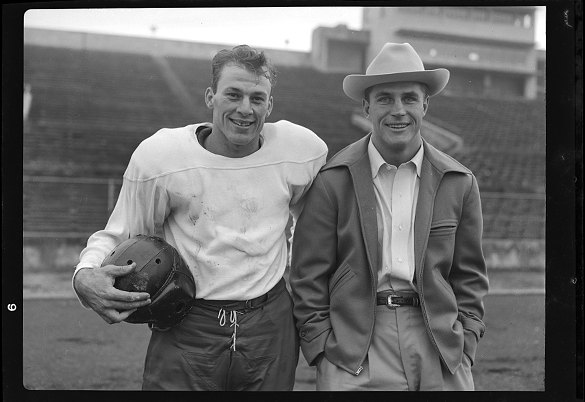

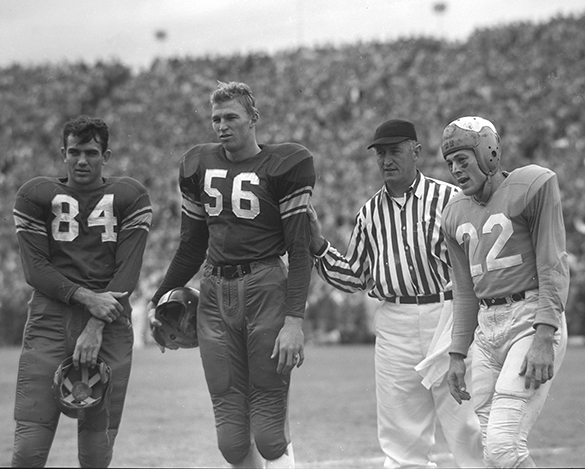

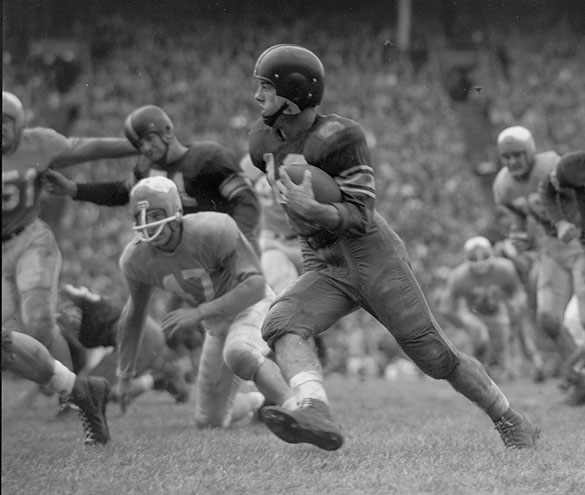

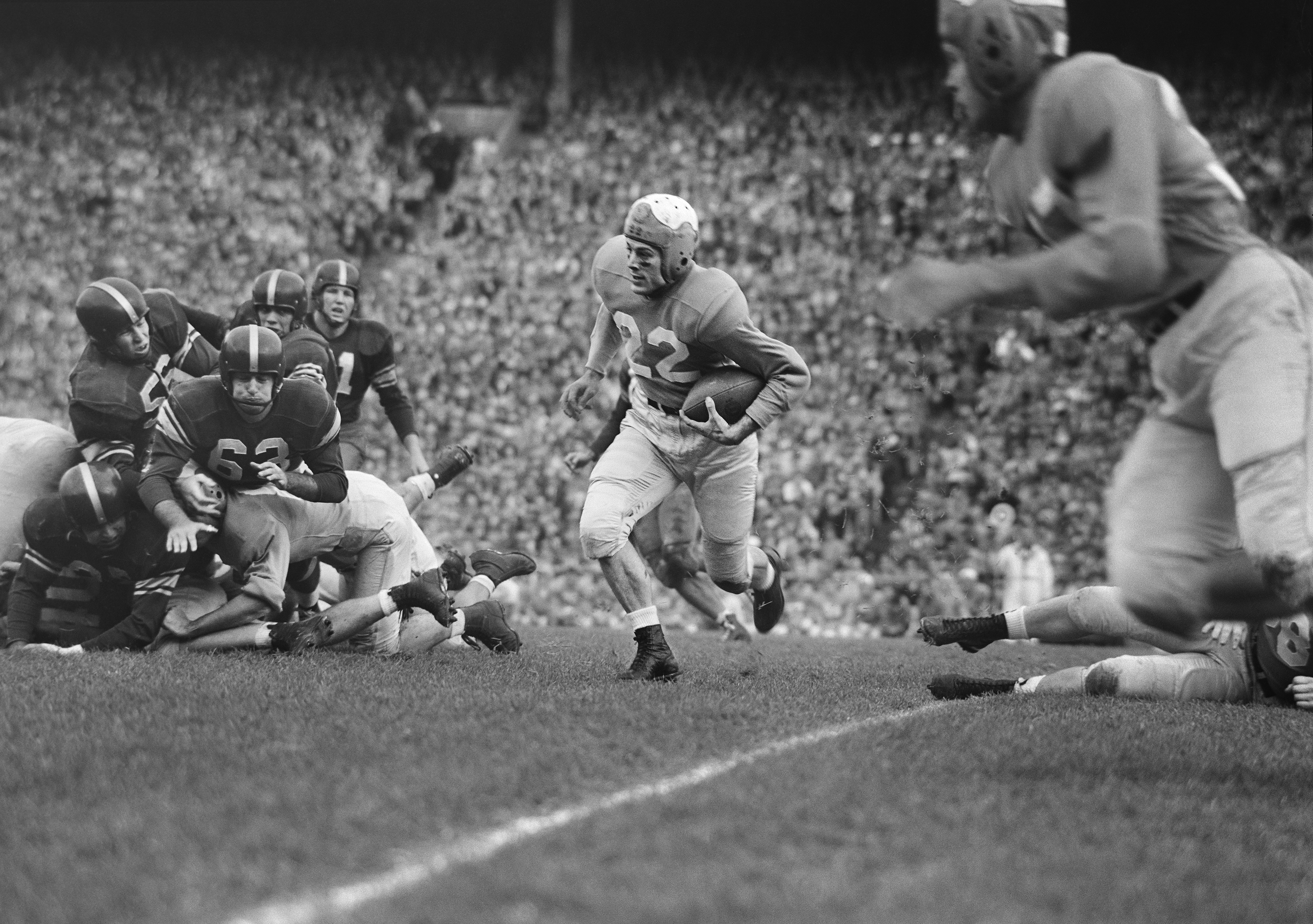

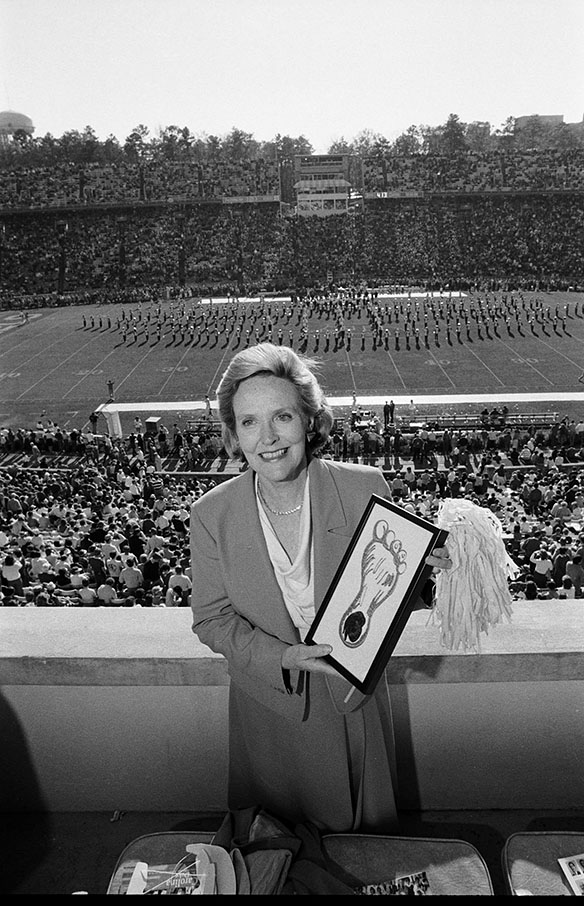

Kyser returned to the UNC campus several times during his musical career. He often recalled in later interviews, how much he enjoyed the Carolina–Duke football games in 1939 and 1948.

In a Charlie Justice profile in Sports Illustrated magazine in October of 1973, Kyser stated: “It is simply a matter of thinking it through . . . all this glamour can end quite suddenly, so you have to think where you will be when the superficialities are through. I watched UNC football legend Charlie Justice when he was on top. I was up to here at the time with my own entertainment career, so I was looking to see if it was getting to him. It takes a thief to know one, you know. I tell you, when they recruited Charlie to play here, after his great football career in the Navy, it was a little like getting Clark Gable to appear in a local little-theater production. He was a star even before he got here.

“But Charlie was just the opposite of a prima donna. It never got to him, as it has to so many people in entertainment . . . .”

“Let me tell you a little story. I took Charlie to a big Hollywood party once. The Hollywood people were dying to meet him. Charlie was flabbergasted. His face must have fallen a foot when he walked into that place. He didn’t act like a football hero at all. He acted like the smallest of small-town hicks. He was the one impressed with them. All those movie stars. He’d never seen anything like it. I remember he came over to me and said, in that high voice of his, ‘Man, this is tall cotton.’ He just kept on saying it: ‘Taaa-lll cotton.’”

Kay Kyser passed away on July 23, 1985 in Chapel Hill. He was eighty years old.

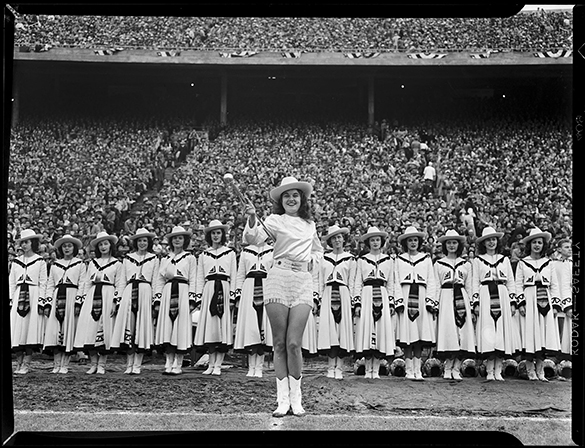

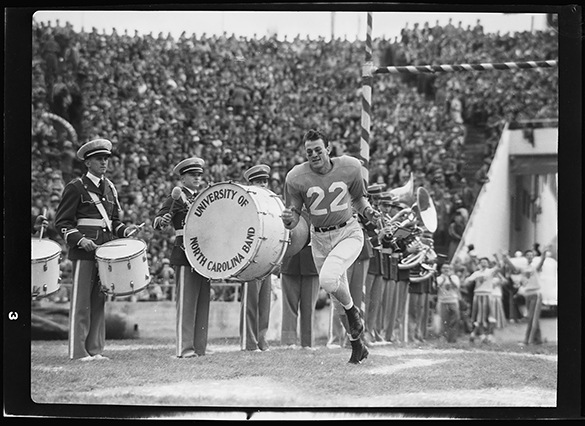

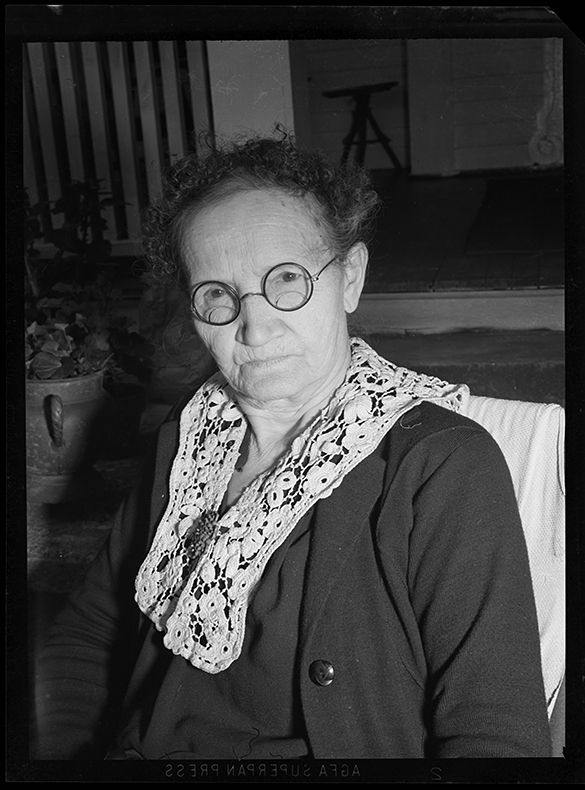

Actress and singer Georgia Carroll Kyser, wife of Chapel Hill bandleader Kay Kyser, at a football game in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Kenan Stadium. The Carolina Band in the background was playing “Tar Heels On Hand” to honor Kay Kyser.

Kyser’s wife Georgia Carroll remained in Chapel Hill until her death in 2011 at age 91. She donated Kyser-related photographs and papers to the university. You can still see Kay’s picture in The Carolina Inn on the UNC campus and he is enshrined in the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame. But for the most part, you won’t find many people who know the words to “Three Little Fishies.” Just so you know the words go like this: “Boop boop diddum daddum waddum choo, and they swam and they swam all over the dam.”