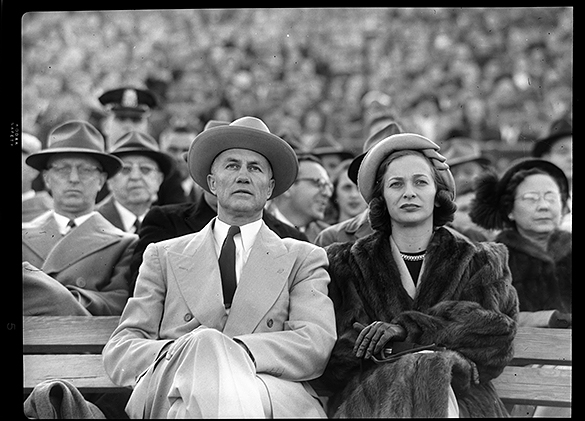

99 years ago today, on October 24, 1915, William Brantley Aycock was born in Lucama, North Carolina. He went on to serve the University of North Carolina for almost 40 years, from a faculty appointment in the School of Law in 1948 until his retirement as Kenan Professor in 1985. During the years 1957 until 1964, he served as Chancellor of UNC-Chapel Hill. On this special day, Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard recalls Chancellor Aycock’s words from 1957 on a timely campus topic in today’s news.

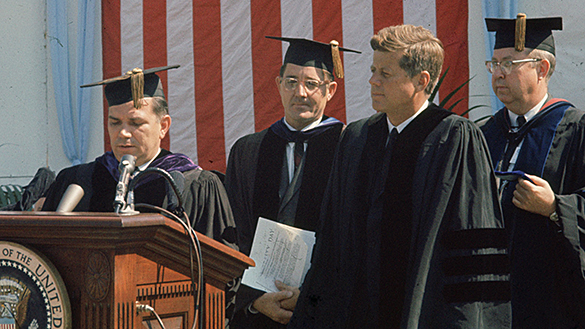

UNC Chancellor William Aycock pictured speaking at podium, with UNC System President Bill Friday, President John F. Kennedy, and Dr. James L. Godfrey at University Day, October 12, 1961, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

When I look at my UNC diploma, two things always grab my attention . . . aside from the fact that it says I earned a degree. There are two signatures on the document that always remind me that I was part of a very special time. William C. Friday was President of the Consolidated University and William B. Aycock was Chancellor of UNC-Chapel Hill when I was there from September of 1958 until January of 1963. These men of integrity signed my diploma and led the University of North Carolina to a place at the top of the top.

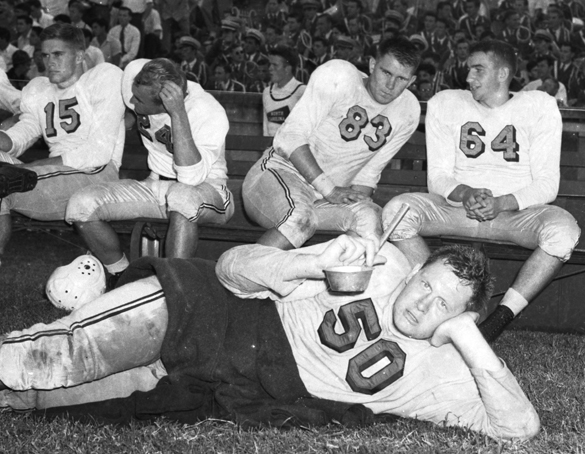

On Thursday, July 15, 2010, my wife Marla and I attended the 90th birthday party for Bill Friday at the UNC Alumni Center on the UNC campus. What a special day . . . honoring the man who defines the word integrity. The following morning, as I opened the Greensboro News & Record, looking for a story of Friday’s birthday party, I was struck by the headline which read, “NCAA Investigates UNC Athletes.” As I read the story, I kept thinking about my time at UNC and how Bill Friday and Bill Aycock would have never let anything like this happen. Unfortunately, that story from July 16, 2010 is still with us.

As we celebrate Bill Aycock’s 99th today, here, in his own words from a talk to UNC alumni in Washington, D. C. in May 1957, is his take on intercollegiate athletics:

I am not disturbed that alumni groups have a strong interest in athletics because I believe that the interest manifested by most alumni in intercollegiate athletics is but a symbol of a deeper interest in the totality of the programs, hopes and aspirations of the whole institution.

I believe that those alumni whose affection for the University both begins and ends with intercollegiate athletics are few in number. Unfortunately, there are some among those few who seem to entertain a misguided notion that in athletics the means are not too important if the end is victory on the scoreboard. In those institutions, including ours, which have undertaken an extensive intercollegiate athletic program, it is not realistic in my judgment to try to separate athletics and education. A grant-in-aid program enables students with athletic ability to secure a college education. It is only on this basis that a University can justify such a program. Since the University is involved in the rewarding of scholarships, it is very essential that grants-in-aid be administered in accordance with the letter and spirit of the rules and regulations. Further, a student who is an athlete should not be treated differently from a student who is not an athlete. There must be no double standard. Moreover, no program in the University, including athletics, should be conducted in such a manner as to lower either moral or academic standards. He, who would insist on practices which nibble at and dilute the integrity and educational standards of this institution, is no friend of athletics or of his institution. The two are not to be separated because, in matters fundamental, athletics and the University must rise or fall together. I regard this to be of such importance that I shall in the days to come frequently discuss the administration of our athletic programs with our alumni groups.”

Six months later in a statement to the Durham Morning Herald on November 27, 1957, Bill Aycock added this:

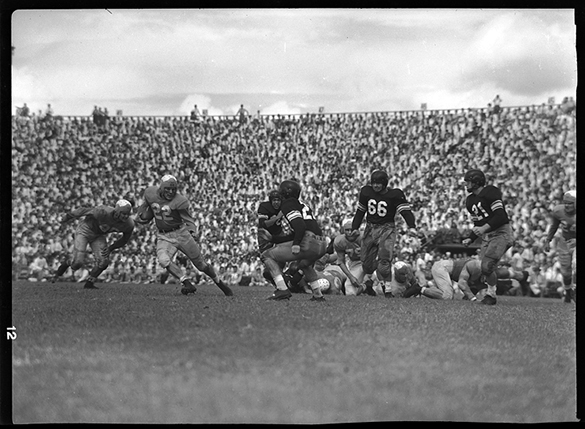

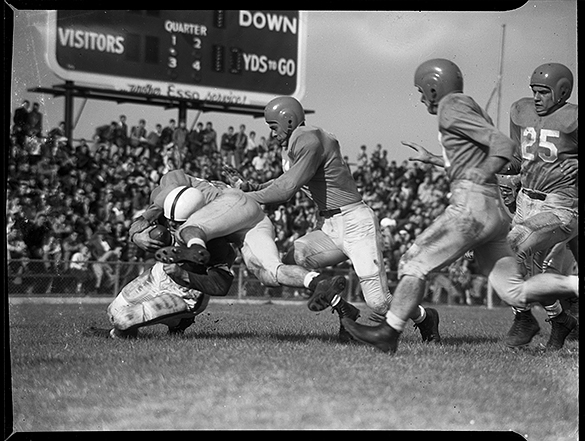

There are now, as there have been in the past, many people within and without the university who believe that intercollegiate football should not be part of the university. On the other hand, many people within and without the university believe intercollegiate football is an important part of modern university life. Regardless of the merits of this question, it is clear that the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill carries on an extensive intercollegiate football program.

The precise values of this program are difficult to determine. Once committed to an extensive intercollegiate athletic program of fundamental principle is to regard each member of the student body as a student first and his athletic participation as secondary to his primary mission of securing a university education.

In order to accomplish this, a large body of rules and regulations has developed within the institution and within various conferences in which we are members. Adherence to these rules and regulations is the most tangible means to insure that the primary role of the university is not superseded by secondary activities.

Further, admission standards and rules controlling eligibility to remain in the university must be made without regard to the effect which they would have on the admission and retention of athletes.

In the light of the foregoing criteria, I think that intercollegiate football is playing its proper role in the country.

The question of bigness is a relative one and must be judged in light of particular circumstances. Theoretically, the larger the program the greater the temptation to depart from the rules and regulations and principles set forth above. However, realistically, it simply means that greater care on the part of everyone concerned is essential to insure that excesses do not prevail.

Notwithstanding the size of the program, in this university we shall adhere to the standards and rules and regulations in intercollegiate athletics and insist that scholarship and academic excellent is paramount.

![Former UNC Chancellor William Aycock and UNC Head Basketball Coach Dean Smith posed together for Hugh Morton's camera in January 1990. This photograph appears in Art Chansky's THE DEAN'S LIST published in 1996, though cropped more tightly here. Ironically, it illustrates the chapter "The Writing on the Wall," which recounts the story surrounding NCAA infractions under head coach Frank McGuire during the 1960-61 season. In that same chapter, Chansky describes Aycock's small office in the Van Hecke-Wettach Hall where Aycock worked as professor emeritus in the law school. On one of the walls was "a picture of him with Dean Smith taken a few years ago by honored photographer Hugh Morton. Aycock received a copy of the picture from Smith with a personal note on the back . . . It says simply, 'This is the only picture of me in my office.'" That photograph is likely the one shown here. [Clicking on this image will take you to a scan in the online Morton collection for different pose from the same photographic session.]](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2014/10/P081_NTBR2_002988_02_crop.jpg)

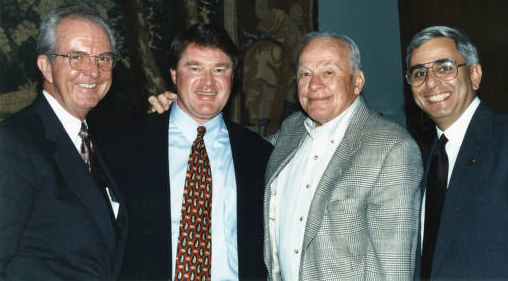

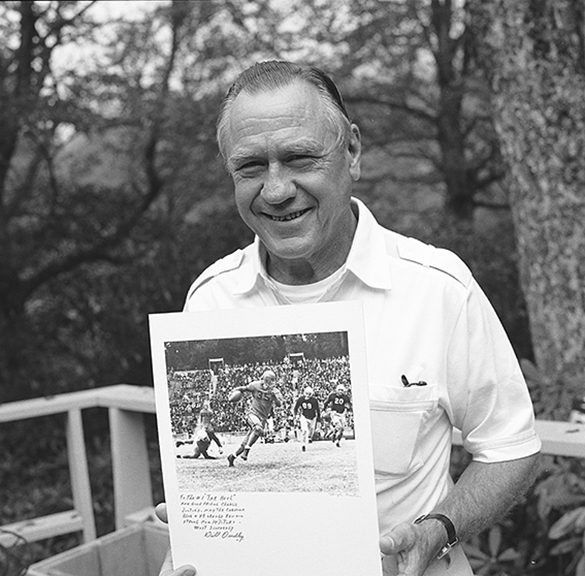

Former UNC Chancellor William Aycock and UNC Head Basketball Coach Dean Smith posed together for Hugh Morton’s camera in January 1990. This photograph appears in Art Chansky’s THE DEAN’S LIST published in 1996, though cropped more tightly here. Ironically, it illustrates the chapter “The Writing on the Wall,” which recounts the story surrounding NCAA infractions under head coach Frank McGuire during the 1960-61 season. In that same chapter, Chansky describes Aycock’s small office in the Van Hecke-Wettach Hall where Aycock worked as professor emeritus in the law school. On one of the walls was “a picture of him with Dean Smith taken a few years ago by honored photographer Hugh Morton. Aycock received a copy of the picture from Smith with a personal note on the back . . . It says simply, ‘This is the only picture of me in my office.’” That photograph is likely the one shown here. [Clicking on this image will take you to a scan in the online Morton collection for different pose from the same photographic session.]

At the end of the 1960-61 UNC basketball season, Chancellor Aycock forced head basketball coach Frank McGuire to resign following allegations of recruiting violations. Aycock then promoted 30-year-old assistant coach Dean Smith, whom he had hired three years before, to the head coaching position and told him “wins and losses do not count as much as running a clean program and representing the University well.”

This past May during Graduation/Reunion weekend, the UNC General Alumni Association presented a program honoring the legacy of both Friday and Aycock. GAA President Doug Dibbert related a Bill Aycock story that resonated with a full house in the UNC Blue Zone.

The story goes something like this. During the 1961-62 basketball season, Dean Smith’s team won only 8 games. When the season ended, two or three prominent alumni called and asked to meet with Chancellor Aycock about the 8-win-basketball season. They told the chancellor he needed to replace Smith as soon as his contract was up. After listening to the alums for several minutes, Aycock excused himself and left the room. When he returned he said: “Gentlemen I’d like to inform you that I just extended Dean Smith’s contract. Now, are we done here?”

Epilog

Wednesday, October 22, 2014 saw the release of the long-awaited “Wainstein Report,” formally titled “Investigation of Irregular Classes in the Department of African and Afro-American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.” The 136-page report links individuals in the “Academic Support Program for Student Athletes” to fake “paper classes” in that department between 1993 and 2011. The UNC website devoted to this topic is called “Our Commitment: Taking Action and Moving Forward Together,” which includes links to a video of the press conference and a PDF of the report.