A landmark on the UNC campus celebrate its 101st birthday today, June 2, 2014. Morton collection volunteer Jack Hilliard and I take a combined look at this Tar Heel icon.

Stephen Fletcher:

Perspective and context are two hallmarks of photography—just as they are with all the arts. The photographer’s viewpoint shapes a photograph’s subject and how he or she frames the subject (by what it contains and eliminates) narrows the story or emotions that subject conveys. As a UNC student and alumnus, Hugh Morton photographed UNC’s Confederate Monument, only a sampling of which appears in the online collection.

The Confederate Monument, commonly known as “Silent Sam,” is a controversial landmark on the UNC campus. Last year—Sunday, June 2nd, 2013—marked its 100th anniversary. There was no official recognition of this milestone. All, however, was not quiet for afternoon saw nearly 100 people attend a Real Silent Sam Committee protest rally. The Friday before, the University Archives blog For the Record posted two documents: a letter written by then-UNC president Francis P. Venable to James G. Keenan expressing his desire that its design not be a monument to the dead “but to a noble idea,” and two pages from Julian S. Carr’s dedication speech laced with Anglo Saxon supremacy and racial violence.

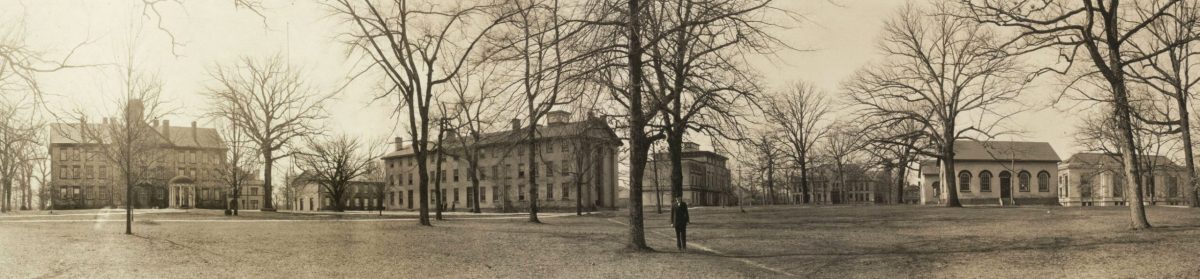

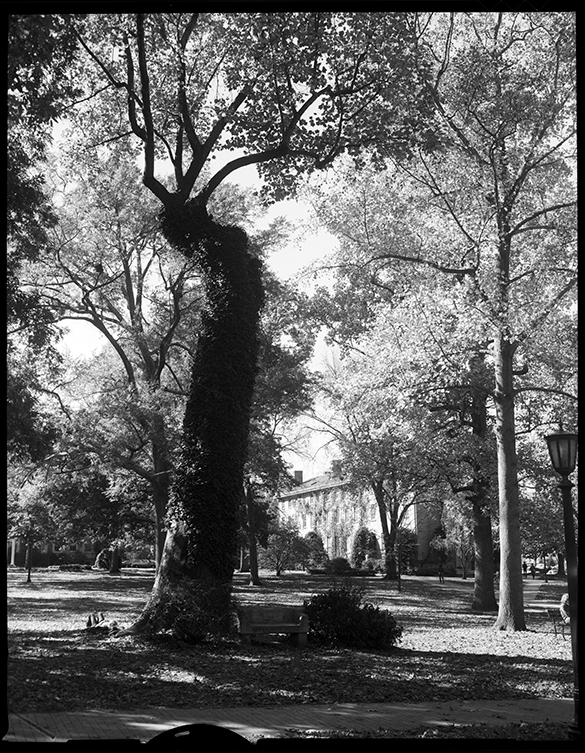

As you approach the statue today, its context is vastly different from those who knew the landscape in 1913. The monument sets near the edge of wooded McCorkle Place, at the time the only campus quadrangle. As Jack writes below, “In its park-like setting, many only see Silent Sam as a nice place to sit on a warm spring day and enjoy the beauty of William Meade Prince’s ‘Southern Part of Heaven.’” As one looks deeper, however, one finds more meaning in the monument’s geographical context and the perspective of those who built it in their place in time.

In 1913 University leaders erected the northwest–facing statue near the northernmost point on the campus. Nearby to the monument’s southwest are three buildings, architecturally connected, named Pettigrew Hall, Vance Hall, and Battle Hall—all completed the previous year. James Johnson Pettigrew, UNC class of 1843, was a Brigadier General in the Civil War, shot and killed while retreating less than two weeks after playing a major role in the Battle of Gettysburg. Zebulon Vance was North Carolina’s Civil War governor. Kemp Plummer Battle, during the Civil War era, was a delegate to the Secession Convention in 1861, president of the Chatham Railroad that hauled coal from mines in Chatham County to Confederate armament factories, and a trustee of the university. He would later become university president. The monument, in contextual words, was symbolically set before three Confederate stalwarts.

Jack Hilliard:

More than 1,000 university men fought in the war. At least forty percent of the students enlisted—a record unequaled by any other institution, North or South. At their convention in 1909, the North Carolina Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy decided to honor the 321 UNC alumni who died in the Civil War, as well all students who joined the Confederate Army. Supporters raised $7,500 to erect a seven-foot statue, commissioning Canadian sculptor John A. Wilson to do the work.

The dedication and unveiling was held 101 years ago on June 2, 1913 with University President Francis P. Venable pulling off the concealing curtain and North Carolina Governor Locke Craig, UNC class of 1880, as principal speaker. The statue’s dedication plaque reads: “To the sons of the university who answered the call to their country in the War of 1861-1865, and whose lives taught the lesson of their great commander that Duty is the sublimest word in the English language.”

The youths, buoyant and hopeful that had thronged these halls, and made this campus ring with shouts of boyish sports, had gone. The University mourned in silent desolation. Her children had been slain . . . this statue is a memorial to their chivalry and devotion, an epic poem in bronze. The soul of the beholder will determine the revelation of its meaning. —Governor Locke Craig, from his dedication speech.

Also speaking at the dedication was the chair-person of the monument committee, Mrs. Bettie Jackson London. In her speech she said: “In honoring the memory of our Confederate heroes, we must not be misunderstood as having in our hearts any hatred to those who wore the Blue, but we do not wish to forget what has been done for us by those who wore the Gray.”

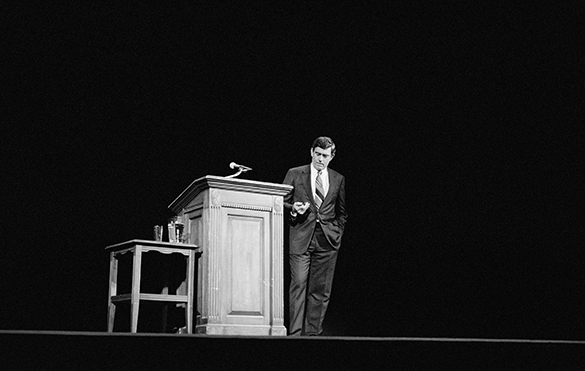

Representing the Confederate veterans was Gen. Julian Shakespeare Carr, UNC Class of 1866. Carr, namesake of nearby Carrboro and whose name is on at least one UNC campus building, captured the spirit of the times in his speech.

“The present generation, I am persuaded, scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo Saxon race during the four years immediately succeeding the war, when the facts are, that their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South.” Carr went on to say that the “purest strain” of white blood was still to be found in the South at the time, because of the duty performed by Confederate soldiers.

After the speeches, a quartet sang “Tenting on the Old Campground Tonight,” while the estimated crowd of one thousand got a close-up look at the work of art.

In his 101 years, Silent Sam has often been the subject of controversy. There are those who think the statue is a symbol of racial oppression and there are those who believe it to be a symbol of regional pride.

On his 100th birthday, on June 2, 2013, Silent Sam had to once again endure some shots . . . this time verbal shots from a group of protestors from “The Real Silent Sam Movement,” who said the statue represents a racist past that continues in some places today.

“The reality is that Sam has never been silent,” state NAACP President Rev. Dr. William J. Barber told the crowd of about 85. “He speaks racism. He speaks hurt to women—particularly black women. And he continues just by his presence to attempt to justify the legacy of the religion of racism.”

From time to time the statue has been covered with graffiti calling for an end to violence and war, as evidenced by Hugh Morton’s photographs from April 1968. It has often been covered with dark blue paint from Duke or red from State. Through controversy and vandalism, Silent Sam endures, continuing his watchful eye. The area around the statue has often been and continues to be a place where students can gather and speak out on issues of the day. And then there are those who view Silent Sam as simply a nice place to sit on a warm spring day and enjoy the beauty of William Meade Prince’s “Southern Part of Heaven.”

Stephen Fletcher:

Last year when University Archives

posted documents from Carr’s speech, then University Archivist Jay Gaidmore wrote: “Over the recent decades, Silent Sam has become a symbol of controversy, caught between those that believe that it is an enduring symbol of racism and white supremacy and defenders who contend that it is a memorial to those UNC students who died and fought for the Confederate States of America. Could it be both?”

At the time of the unveiling, it would seem not. H. A. London was a one of those students who left UNC to fight for the South. On June 2nd, 1913 he introduced Governor Craig at the dedication ceremony as Major H. A. London (and husband of Betty Jackson London). As he concluded his introduction, London harkened the students who pursued their “devotion to duty.” Of their duty London said, “We thought we were right, and now we know it.

Hopefully in our time we can acknowledge that there are indeed very different perspectives about this monument—especially respecting those whose viewpoints were, by the very nature of their exclusion from speaking at the dedication ceremony, kept silent.