From the Hillsborough Recorder, 29 November 1829.

On November 20, 1829, a slave by the name of James abandoned his station as a “college servant” at the University of North Carolina. A few days later, one “S.M. Stewart” placed an advertisement in the Hillsborough Recorder, the Petersburg Intelligencer, and the Norfolk Herald in which he offered a $20 reward for James’s recovery.

The advertisement Stewart placed begins:

TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD. Ran off from the University, on the night of the 20th instant, a negro man by the name of JAMES, who has for the last four years attended at Chapel Hill in the capacity of a college servant.

There are at least two possible explanations for James’s presence in Chapel Hill. Until 1845, UNC students were allowed to bring enslaved servants with them to campus. However, the description of James as a “College Servant” could have meant that James also served other students on campus. Early UNC students paid a fee for “servant hire,” which the University used to lease servants from local slaveholders. The college servants were employed in a number of jobs, including cleaning the rooms, tending fires, cooking, caring for animals, and work on the grounds. Some well-known enslaved college servants, such as November Caldwell and David Barham, worked on the campus for many years and were remembered fondly by students. What little we know about James at this point we have to infer from ad:

He is of dark complexion, in stature five feet six or eight inches high, and compactly constructed; speaks quick and with ease, and is in the habit of shaking his head while in conversation. He is doubtless well dressed, and has a considerable quantity of clothing.

James is described in detail, not only regarding his physical appearance but his mannerisms and habits as well. The more detail provided about a runaway, the more likely the chance of success in someone recognizing them from the description. Complexion featured as the primary means of identification in slave advertisements, both for slave sales and for runaways — slave traders and slaveholders had developed a language that formalized apparent differences in skin tone into racial categories.[3] Thus the ad identifies James as “dark” and “compactly constructed,” (probably meaning he was somewhat thin) as well as of average height for the period.

It is presumed that he will make for Norfolk or Richmond with the view either of taking passage for some of the free states, or of going on and associating himself with the Colonization Society.

The fact that S.M. Stewart, who placed the ad, expected James to head for Norfolk or Richmond, both port cities, and went to the trouble of placing the same ad in those locales’ newspapers meant Stewart likely had, or presumed he had, some knowledge of James’s intentions. While many runaway advertisements emphasized enslaved peoples’ families as potential destinations, Stewart seemed sure that James would attempt to head to the free states via the Atlantic, or go so far as to book passage to Africa through the Colonization Society.

We can also infer that Stewart was especially interested in capturing James by the amount he offers as a reward.

A premium of twenty dollars will be given for the apprehension of said slave. The subscriber would request anyone who may apprehend the boy to direct their communications to Chapel Hill. S.M. Stewart. November 24.

In 1829, a $20 reward would be equivalent to about $500 today.[1] Stewart likely came from a wealthier family if he could afford to pay others to track down his escaped “servant,” and could provide a relatively substantial award.[2]

Who Was S.M. Stewart?

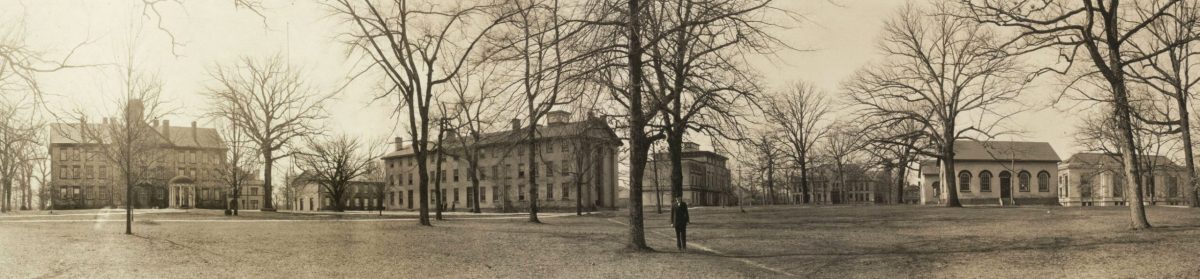

The man who placed the advertisement appears to have been Samuel M. Stewart, a young white man who attended UNC in the 1820s, earning a BA in 1823 and a master’s degree in July 1829.[4] We know more about Stewart than we do James due to a larger paper trail. The daily lives of enslaved people, particularly women and children, often prove difficult to reconstruct as a result of “archival silences” – gaps in what was documented and what documentation was preserved.[5] It is thus primarily through Stewart and the advertisement he placed that we can learn more about James.

Stewart hailed from nearby Chatham County in North Carolina, just a few miles from Chapel Hill, and first entered the university as an undergraduate freshman in 1820. He graduated from the university in 1823 with 29 other young men who became leaders in politics, business, religion, and education.[6] Per newspaper articles from the period, Samuel passed his exams but did not merit any honors as a scholar.[7] He was a member of the Dialectic Society; one of his musings on fame is available in Wilson Library.[8]

We have not yet been able to find any additional information about Stewart after he left UNC in 1829. His entry in the Alumni History of the University of North Carolina lists only the years he earned his degrees; there is no information about his life or career after he graduated. A search of North Carolina census records in 1820 names several potential Stewart households in Chatham and Orange counties. In order to narrow down the results, information such as the fact that Samuel M. Stewart would likely have been around 14 when he entered the university as a freshman can prove helpful.[9] A search for families with males between the ages of 10 and 18 narrows down the pool to three households in Orange County: Charles Stewart’s household, which consisted of 9 free whites and 6 enslaved blacks; Samuel Stewart’s (1) household, which consisted of 11 free whites and 5 enslaved blacks; and another Samuel Stewart (2), whose small household had only 3 free whites. Samuel Stewart (2) can probably be ruled out as the household to which Samuel M. Stewart belonged; as a non-slaveholding small farmer, Stewart (2) would have been unlikely to send his only son to a university in this period. However, it is possible that Samuel M. Stewart indeed hailed from this household, and that he hired James’s service as a servant from another slaveholder (a practice common among UNC’s students) after arriving in Chapel Hill.[10] Furthermore, the reward Samuel offered in the runaway advertisement indicates a certain degree of wealth that most small farmers’ sons would be unable to offer in this period. The 1830 census shows only one “Laml Stewart” household, but the males of the household are too young to have been the correct Samuel Stewart. It appears that Samuel M. Stewart departed from Chapel Hill between the time he placed the advertisement in November 1829 and the census was taken.

From the records we’ve examined so far, we do not know what happened to Stewart or to James. Neither one left an easy-to-follow paper trail, but there are still many possibilities for further research, including census records from other states, probate records, court records, and more. It is our hope that as we discover and share more about the history of slavery at the University, we can inspire and encourage others to explore further and help to expand our understanding of the role of slavery and enslaved people at UNC.

Suggested Further Reading

Freddie L. Parker, Running for Freedom: Slave Runaways in North Carolina, 1775-1840 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1993)

Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999)

John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

Thavolia Glymph, Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 2014)

Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016)

Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (Boston: Beacon Press, 2017)

Notes

[1] “$20 in 1829 → 2018 | Inflation Calculator.” FinanceRef Inflation Calculator, Alioth Finance, accessed Jan. 20, 2018, http://www.in2013dollars.com/1829-dollars-in-2018?amount=20.

[2] John Hope Franklin and Loren Schweninger, Runaway Slaves: Rebels on the Plantation (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 167-168.

[3] Walter Johnson, “The Slave Trader, the White Slave, and the Politics of Racial Determination in the 1850s,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 87, No. 1 (Jun 2000), 13-38.

[4] Freeman’s Echo (Wilmington, NC), Jul. 11, 1829.

[5] Enslaved people are not often found in the genealogical histories of the white families who bought them, enslaved them, and sold them. Nor were enslaved peoples’ names, birth dates, family members, professions, and addresses included in any census or in most records until after emancipation. Prior to 1870, only free black men entered the census record with names. From 1790 to 1860 the census only enumerated enslaved black people as part of whites’ personal wealth, and then by age, sex, and coloring. Enslaved people most often entered the historical record in glancing mentions made by literate whites in the antebellum era. Enslaved peoples’ further lack of control over their own names and homes as part of a paternalist and racialized slave system creates difficulties in locating particular individuals. Court cases, deeds, bills of sale, marriage records, county will books, probate records, and runaway slave advertisements remain the primary means by which to secure the names of slaves and details about their lives.

[6] Kemp Battle, History of the University of North Carolina, Volume I: From Its Beginning to the Death of President Swain, 1789-1868 (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company, 1907), 791.

[7] “University,” The Raleigh Minerva (Raleigh, NC), Jun. 30, 1820; “University of North Carolina,” The Hillsborough Recorder (Hillsborough, NC), Jun. 13, 1823.

[8] Samuel M. Stewart, “Inaugural Address, 26 March 1823,” Dialectic Society of the University of North Carolina Records, 1795-1964.

[9] Battle, 571.

[10] Ibid, 230.

[11] William Mebane, “Five Dollars Reward” North Carolina Journal (NC) Mar 3, 1797; Solomon Neville, “Fifty Dollars Reward,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser (NC), Sept 16, 1814; Solomon Neville, “Twenty Dollars Reward,” The Star (NC), Apr 5, 1811; Wyatt Ballard, “Ran Away,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser (NC), May 21, 1804; Charles King and Stephen Lloyd, “Notice,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser (NC), Oct 6, 1805.

[12] Christopher Barbee, “Ten Dollars Reward,” Hillsborough Recorder (NC), Jul 25, 1831; E. Mitchell, “Fifty Dollars Reward,” North Carolina Standard (NC), Mar 13, 1835; Charles R. Yancey, “30 Dollars Reward,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser (NC), Jan 9, 1829; Louisa S. Thompson, “Fifty Dollars Reward, Stop the Runaways,” The Weekly Standard (NC), Aug 12, 1846; Joseph Hawkins, “$50 Reward for Cut-Finger Cad,” Raleigh Register and North Carolina Weekly Advertiser (NC), Feb 11, 1825.