Category: Uncategorized

Trans Pacific Partnership Could put U.S. Intellectual Property Law in a Bind

Talk of the Trans Pacific Partnership has been in the news a lot recently; however, certain specifics about the deal itself have been more difficult to come by. The agreement is between Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States and Vietnam and it “eliminates tariffs on goods and services, tears down non-tariff barriers, and harmonizes regulations.” The agreement is made up of many different chapters that cover a broad number of topics and “sets down 150 negotiating objectives, such as tough new rules on intellectual property protection, lowering of barriers to agricultural exports, labor and environmental standards, rule of law and human rights….Congress would demand a loosening of restrictions on across border data flow, an end to currency manipulation, and rules for competition from state-owned enterprises.” With such an expansive list of goals and the level of significance this treaty would have, it’s no surprise that the amount of secrecy surrounding the terms and negotiations has people worried. The deal is under strict confidentiality until a final draft is produced, so the information made available thus far has either been chosen for release or leaked to the public.

One of those leaked sections was the chapter on Intellectual Property, which has raised many concerns. The chapter covers patent, trademark and copyright law and all countries involved in the agreement must follow the laid out requirements. In many ways the requirements are similar to current United States law, which is different, and in some areas, stricter than international policies. By forcing other countries to follow the United States’ strict laws, this will inhibit them from developing their own IP legislation, and it may force them into policies that have more benefits for large copyright owners and less room for innovation.

There is also an additional issue that arises from the agreement when it comes to arbitration. As of right now, certain breaches of the pact will be resolved by three arbitrators that are picked by the involved parties to oversee the process. However, since these arbitrators are not elected judges and will be determining “whether governmental actions, which are designed to protect our health, safety and environment and economic well-being, are consistent with the TPP[,]” there is a question of whether this decision making is constitutional.

However, for copyright law specifically, the TPP could mean big changes. For example, safe harbor provisions under the DMCA may no longer apply to some large intermediary websites such as YouTube and Google, and the duration of copyright ownership may be extended by decades, which could lead to significant problems for some newer public domain works in countries with shorter copyright terms.

The TPP seems to have a long road ahead before it is fully accepted and signed into effect, so in the meantime we’re left to wonder about the fate of these terms. If the TPP were to pass as is, copyright law could be changed without formal legislation and after being drafted mostly in secret, so many in the IP field are concerned about the extensive effects the deal will have. Many questions are left open about what will be retained from U.S. copyright law, what will be applied from it to other countries, what will change altogether, and with such a lack in transparency, these questions may unfortunately remain open for a while.

To Copyright or Not to Copyright?: How Oracle v. Google May Cause Issues for Future Software Development

When it comes to copyright law, software and how it should be copyrighted can be a complicated issue to tackle. The recent Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google, Inc. case is a prime example of this.

The company Oracle owns software which is a modified version of Javascript that allows for different kinds of programs to communicate and be compatible with each other. This type of software is called Application Programming Interfaces, or APIs. In this case, Google used Oracle’s APIs without permission in order to create Android and its mobile operating system, which prompted Oracle to sue Google and claim that this constituted copyright infringement. Once the case was brought to court, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California sided with Google, stating that these APIs were “methods of operation” which cannot be copyrighted under 17 U.S.C. § 102(b). However, on appeal in the Federal Circuit court, the decision was reversed and that court sided with Oracle stating that the APIs were in fact copyrightable material. The Supreme Court has denied to grant certiorari and hear the case, leaving many people disappointed, so now the case will be heard once more in district court where Google will try to show that its use of the APIs was fair use.

With the Supreme Court not making a decision on whether or not APIs can be copyrighted, this makes this case simply another fair use case. If the court sides with Google once more and determines its use was indeed fair, then this case can be used as precedent for other coders and software developers who get sued for using APIs later on down the road. However, each fair use decision relies on the specific details of that case, and the outcome is ultimately left to whatever court making that decision. Without a Supreme Court ruling that states whether APIs are copyrightable or not, there is no solid precedent for software developers to rely on, and using APIs without permission will still be risky.

APIs are crucial to interoperability between programs, and are a vital factor when it comes to being able to code and create new products. So deciding whether or not these interfaces can be copyrighted by a single company is concerning to many people in the software development field. If certain coders are familiar with a particular form of APIs, but they don’t have permission to use them and are afraid of being sued for copyright infringement like Google has been, new developments could be delayed. This potential lag could last for the amount of time it takes for the coders to learn how to use a new API, or get permission from the owner, or it could mean a complete halt altogether if the risk of a pricey lawsuit doesn’t seem worth it.

Other companies’ practice with regard to the use of APIs and similar programs without permission may depend on Google’s success with its fair use argument. Even if Google prevails, companies may decide that the chance of a lawsuit does not make it worth the risk at all.

Criminal Minds Think Alike: The Problem Social Media Presents in Elonis v. US

It’s not news that social media has become a large part of everyday life for many people. Facebook. Instagram. Snapchat. All are platforms that have increasingly replaced face to face interactions and communications. They allow people to stay in touch, share pictures of their pets, or sometimes reveal their most disturbing thoughts during a dark time.

This is what happened with Anthony Elonis in the recently talked about Elonis v. United States case. Elonis was going through a divorce when he began posting controversial “lyrics” to his Facebook page under the pseudonym “Tone Dougie.” He made unusual and violent comments about his ex-wife, police officers, patrons of the park where he worked, and even a kindergarten class. His remarks resulted in him losing his job, and his ex-wife obtaining a three-year-protection-from-abuse order in court against him. On top of that, Elonis was brought in for criminal charges under 18 U.S.C. § 875(c) for “transmit[ting] in interstate or foreign commerce any communication containing any threat to kidnap any person or any threat to injure the person of another….” Elonis claimed that his First Amendment right to free speech allowed him to make these comments online because they were not a “true threat.”

While important issues regarding the First Amendment and free speech may seem prevalent in a case such as this, the Supreme Court didn’t discuss them. Chief Justice Roberts wrote the majority opinion that stated the true issue here was that the jury that convicted Elonis of communicating interstate threats was instructed to use the wrong standard when determining if he met the elements of the crime. The district court instructed the jurors by saying that “[a] statement is a true threat when a defendant intentionally makes a statement in a context or under such circumstances wherein a reasonable person would foresee that the statement would be interpreted by those to whom the maker communicates the statement as a serious expression of an intention to inflict bodily injury or take the life of an individual.” The court of appeals reviewed and agreed with these instructions, so the Supreme Court granted certiorari to review the case and define the correct standard that should be used.

The criminal statute 18 U.S.C. § 875 does not contain an explicit mentality requirement for communicating threats, and when a federal statute is silent on this issue, the Court reads into that statute a mental standard “which is necessary to separate wrongful conduct from ‘otherwise innocent conduct.’” Which means the defendant “generally must ‘know the facts that make his conduct fit the definition of the offense even if he doesn’t know that those facts give rise to a crime.’” The defendant must be the one aware of his wrongdoing, so Elonis’ mental state is important for determining if he can actually be convicted.

The Government’s argument against Elonis is that since he knew the “contents and context” of his post, and a reasonable person would recognize that the posts would be read as threats, then a conviction can be upheld. However, this reasonable person standard is a negligence standard typically used for tort and civil cases and the Court “has been reluctant to infer that [it] was intended in criminal statutes.” Chief Justice Roberts stated in the Court’s opinion that this reasonable person standard is not enough to convict someone of communicating threats under 18 U.S.C. § 875, and therefore the conviction was reversed and the case was remanded back down to the lower court so that the jury instruction could be modified. The Court did not determine the exact standard for mental state that should be applied for this crime, but only determined that the one used was incorrect.

Determining the correct standard to use in this case could end up being complicated and tedious because of the new territory it’s covering. Technology is continuing to change legal landscapes, and deciding how to interpret threats made online is another example of that. Social media adds an extra level of obscurity to its users and their actions, which not only makes it harder for a court to decide which standard of criminal mentality applies, but also harder for a jury to decide if that standard is met in order to make a conviction. Online posts can be vague, not directed towards anyone specific, and they can make it easier for the defendant to claim he had no intent of wrongdoing while making them. These added complications make presenting evidence and proving the elements of certain crimes difficult. So even though the conviction was thrown out, the Elonis case should still be watched. Whatever standard the lower court uses on remand may end up setting the precedent for similar social media based cases in the future.

Posters in the Digital Repository

Digital repositories seem to have very few poster submissions, which is unfortunate, because digital repositories are the ideal place to record and preserve of academic poster presentations. In this blog post, we will outline four reasons why we believe that digital repositories should prioritize adding poster presentations to the repository.

First, unlike articles, when people submit posters to a conference, the conference does not require the creator to transfer the copyright to the conference. Because the content creator (a professor or student) at the university is more likely to retain full autonomy over the copyright, he or she will probably be able to decide on the permanent home of the poster without consulting anyone.

Second, unlike academic articles, posters are ephemeral. When a journal article is published or a conference paper accepted, there is an expected permanent home for that work, and the author will always be able to find that article or paper, even if they no longer hold the copyright to it. That it is not true with posters, which often do not have a permanent home. Digital repositories can provide that permanent home for facsimiles of the poster, which have not existed before.

Third, because of the ephemeral nature of the posters, when individuals put the poster on their CV, there is not a way for people to review the posters later. By encouraging students and faculty members to place their posters on the repository, they can link to the repository on their CVs or in their grant applications and have their work become readily available.

Finally, by encouraging students and faculty members to upload copies of their posters to the repository, it should be easier to explain to how, why, and when to upload their articles to the repository and to continue to expand the content in the repository.

So when we think about advertising the digital repository to students and professors, let’s not forgot to talk about the importance of posters especially with graduate students. Do you have questions about copyright and the images in your posters? If you have questions about this or anything else, please contact us in the Scholarly Communications Office.

You may be sued . . . or arrested

We often talk about the possibility of copyright infringement when discussing legal issues surrounding data or text mining. Often, the method for text mining is conceptualized as making copies from a database and then mining the copies on a new server. While that is one way to mine, it is certainly not the only way. Another way to text is to mine the database itself, instead of copies of the database.

When considering whether to advise our faculties and researchers on whether they can text mine a database without explicit permission of the publisher or administrator, we must examine the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) as well as copyright law. If we do not conform to the CFAA requirements, it is possible that our libraries and faculty members may face civil, if not criminal liability.

Without consent of the database administrator, mining may be a violation of the CFAA, specifically the hacking section of the act, which has been codified at 18 USC 1030. For context, this is one of the statutes that Aaron Swartz was charged with before his death in 2013. The CFAA is both a criminal and civil statute. This means that the federal government can either prosecute charges under this statute or private individuals or companies can bring a civil lawsuit for monetary damages. Courts have broadly interpreted 18 USC 1030(a)(4), which states that it is a violation of the statute to:

knowingly and with intent to defraud, accesses a protected computer without authorization, or exceeds authorized access, and by means of such conduct furthers the intended fraud and obtains anything of value, unless the object of the fraud and the thing obtained consists only of the use of the computer and the value of such use is not more than $5,000 in any 1-year period;

Courts have defined exceeding authorized access by including text and data mining as a violation of the Terms of Service, which has included text mining a public facing website. At this point, no one has been convicted for text or data mining, as a criminal manner, although this is possible.

In both the 1st and 2nd Circuits, the courts have found that plaintiffs could sue and win for text mining as a hacking standard under 18 USC 1030. In both cases from both circuits, the defendants had used robots to access public facing websites and publically available information. In the 1st Circuit case, EF Cultural Travel BV v. Zefer Corp, Explorica, used a robot, or a “scraper,” to crawl EF Cultural Traveler’s website, so Explorica could undercut EF Cultural Traveler’s already low prices. The robot scraped and downloaded the prices (and only the prices) of the flights from EF Cultural Traveler’s website for two years prior to litigation by reviewing the publicly accessible HTML Source code. EF Cultural sued Zefer for downloading from their website, and the court granted a preliminary injunction.

In the 2nd Circuit case, Register.com, Inc. v. Verio, Inc., defendant, Verio, used a robot to submit WHOIS queries to multiple domain name registrars, including the plaintiff, to determine whether new domain names had been purchased. Verio would then solicit the purchasers for website design. Register sued alleging, in part, that Verio had violated 18 USC 1030 when the robot crawled the server. The 2nd Circuit affirmed the district court’s injunction against the plaintiff as the case went to the trial.

Court-issued preliminary injunctions are not final dispositions in cases but do have a high bar. Courts should only grant preliminary injunctions when the person requesting the injunction has demonstrated a substantial likelihood of success on the merits. As can be seen above, the courts have found that civil liability is possible under the CCFA. The CCFA is a criminal statute, and court could find criminal liability as well, although no court has. One requirement is that the infringer must do their action “with intent to defraud.” While this may be a bar for ultimate recovery or a defense to criminal litigation, this might have to go to trial for a jury to decide.

Last year, the House of Representatives introduced House Bill 113-2454, otherwise known as “Aaron’s Law” which would have made violations of terms of service not a violation of the CFAA. However, that bill died in subcommittee during the last Congressional section. Some members of Congress, including Senator Wyden, believe that the law could allow for terms of service violations to be violations of CFAA without clarification in the CFAA.

No court has decided whether faculty members, researchers, and libraries and would be immune under CFAA, and nothing in the statute guarantees that they would be. To advise faculty members to “mine away” without mentioning these issues is irresponsible and may land your library and faculty member in court, if not jail. If you have any questions about this issue or any other, please come see us in the Scholarly Communications Office!

Removing Articles from Predatory Journals

Here in the Scholarly Communications Office, we have had questions about predatory Open Access Journals. Typically, those journals will solicit articles from professors and students on a topic of their choice. Upon submission, the journal will request an Open Access fee. At this point or at other points in the process, if authors attempt to withdraw the paper from publication, the journal publishes the paper without the consent of the author. At this point, the author will generally try and contact the publisher or editor to have the paper removed and the Open Access Journal refuses to remove the paper. This is the point where the question often comes to the library or the Scholarly Communications Officer. Below, we have spelled out one way to get the article removed from the journal’s website. We have been advising authors to file DMCA takedown notices, which have worked fairly well.

It is unlikely that you will know who owns the domain name, so the first thing to do is to determine who you need to send the DMCA takedown notice to. We will be using Wikipedia as an example for a domain name search. To do this you should go to http://www.register.com/ Select the option “WhoIs Lookup” underneath “Domain” At that webpage, type in the domain name. From the Wikipedia article on “Open Access”, the link is http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Open_access, the domain name would be wikipedia.org. Once you are on the “WhoIs Results page” You will find email contact information for the registrar abuse contact information, the registrant email, and the admin email. Additionally, we have advised the professor to email the editor of the journal with the information for the DMCA Takedown notice.

DMCA takedown notices have specific requirements which are the following:

- Identify the copyright holder

- Identify the work or works being infringed (the title)

- Identify the location of the infringed material (URL)

- The author’s contact information (this can be in the signature line)

- Statement of good faith belief

- Statement of accuracy under penalty of perjury.

Here’s an example of a DMCA takedown request from ipwatchdog: http://www.ipwatchdog.com/2009/07/06/sample-dmca-take-down-letter/id=4501/

Finally, remind the professor that even after the material is removed Google will still have it indexed for approximately two weeks after they have taken down the paper, so he/she might still see the paper in Google Search or Google Scholar results for a period of time after it has been removed from the web. If you have any questions about this issue or any other, please come see us in the Scholarly Communications Office!

Buzzfeed and Copyright

Recently, Mark C. Marino, Assistant Professor of Writing at the University of Southern California, wrote a Buzzfeed article entitled 10 Reasons Professors Should Start Writing BuzzFeed Articles. Marino’s article received a lot of press, including a Chronicle of Higher Education post, on whether members of the academy should start writing on Buzzfeed instead of in academic journals.

Whether Buzzfeed is a substitute for scholarly journals is not a subject for the Scholarly Communications Office, but Marino does provide an opportunity to illuminate an important contract term: Buzzfeed allows writers to keep more rights under copyright than many academic journals. When you submit content to Buzzfeed, you grant Buzzfeed “a worldwide, non- exclusive, perpetual, royalty-free, fully paid, sublicensable [sic] and transferable license . . .” (emphasis added) Regardless of how you feel about Buzzfeed or its content, Buzzfeed does not require a complete copyright transfer that is common to academic journals. If an author posts the article on Buzzfeed, the author can use it in their classroom, put it on another website (like a course management system like Sakai or Blackboard), or in their university’s depository without receiving permission from Buzzfeed or determining whether a copyright exception, like fair use, may apply.

Compare Buzzfeed with academic journals. Oxford University Press requires an exclusive license, or a complete copyright transfer. APS Journals also requires a transfer of copyright, as does World Scientific Journals and AIP Publishing. Regardless of how you feel about academic scholarship on Buzzfeed, Buzzfeed allows the author to keep more rights than the previously mentioned academic journals do, and many others. These publishers may require that the author receive permission from the publisher to use their own writing in their classroom, put it on another website (like a course management system like Sakai), or in their university’s depository. You certainly don’t want to have to use a fair use exception to use your own article in your own class, do you? If you have any questions about this issue or any other, please come see us in the Scholarly Communications Office!

Book Drive

Few realize that the Constitution grants Congress the power “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” in Article I, Section 8. This clause has been interpreted as giving power to Congress to create laws governing copyrights and patents.

We now think of the word useful as meaning “being of use or service” or “to serve some purpose.” Useful has an interesting etymological history. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word use comes from Latin, which meant enjoyment with the other definitions we still ascribe to “use” including: to make use of, profit by, take advantage of, apply, consume. Courts and Congress have read enjoyment as part of the useful arts as we grant completely fictitious works copyright protection. So, when you think about “Useful Arts,” remember that is a broad definition where useful includes things that are useful solely because of our own enjoyment.

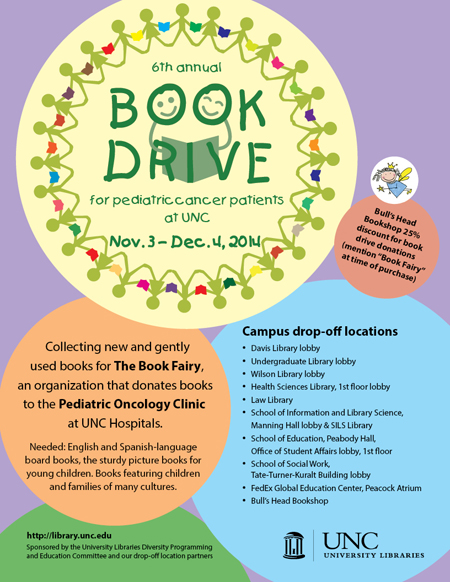

As you are thinking about all of the books that you have enjoyed, perhaps you can consider donating one of those books to the Library’s 6th Annual Book Drive for Pediatric Cancer Patients. You can drop them off at the following locations:

- Davis Library Lobby

- Undergraduate Library Lobby

- Wilson Library Lobby

- Health Sciences Library, 1st Floor Lobby

- Law Library

- School of Information and Library Science, Manning Hall lobby and SILS Library

- School of Education, Peabody Hall,

- Office of Student Affairs lobby, 1st floor

- School of Social Work, Tate-Turner-Kuralt Building lobby

- FedEx Global Education Center, Peacock Atrium

- Bull’s Head Bookshop

In addition, if you can’t part with any of your old favorites, then you can always go to the Bull’s Head Bookshop, mention “Book Fairy” when you buy a book and receive a 25% discount. More information is available here. Remember Friday is the last day to donate!

And, if you have any questions about the purpose of Copyright law, then come in and talk to us in the Scholarly Communications Office!

UNC Annual Book Drive

The UNC University Libraries and its partners (the Health Sciences Library, the Law Library, the School of Information and Library Science, the School of Education, the School of Social Work, the FedEx Global Education Center, and the Bull’s Head Bookshop) are completing its 6th Annual Book Drive for Pediatric Cancer Patients. They are looking for new or gently used books for ages one to mid-teen, especially English and Spanish language board books and sturdy picture books. More information is available here.

When we think about buying a book, we encounter a common misconception of ownership over a physical item. Many people believe that owning of a physical item (like a book) gives them the right to reproduce the book. Copyright law, though, separates physical ownership of an item (like a book) from the ownership of the intellectual property rights in the book. This is why we buy books for book drives rather than make copies. If the library (or anyone else) made copies of books donated from previous years, then whoever made that copy would commit copyright infringement and could be liable for upwards of $150,000 in fines. Honestly, that hypothetical $150,000 would buy a lot of books. So when you purchase the book, it gives you some rights, like the right to resell the book or the right to write your own notes in the book, but it does not give you the right to reproduce the book by making a copy of a loose page or copying the entire book to give to someone else to read.

So, we in the Scholarly Communications Office are encouraging everyone to go into the attic and see if there are any books to donate. The book drive runs through December 4th. If you can’t part with your childhood books, then you can always go to the Bull’s Head Bookshop, who will offer a 25% discount on books for the book drive. At the time of purchase, just mention “Book Fairy.” You can find locations to drop off the books at their website. If you have any questions about what you can do with books that you own or want us to help you find awesome books to donate, contact us in the Scholarly Communications Office!