“Terms of Service; Didn’t Read”

As you use different websites, you might not be asking yourself any questions like: “Who owns this content?” or “Can I actually delete my profile?” or “Will they report this data to the government without my consent or knowledge or a subpoena?” Thankfully, a team of volunteers at “Terms of Service; Didn’t Read” is looking into this for you.

Many of us go through websites and just click through the terms of service agreements with only passably reading the words. For some websites where we do not have to create a log-in (like Songza or Grammarly) we may never read the terms of service at all. “Terms of Service; Didn’t Read” (TOSDR) is an all-volunteer crowdsourced database that evaluates the terms of service of various websites. Currently, TOSDR has evaluated about 70 of the major websites with new ones being added all the time.

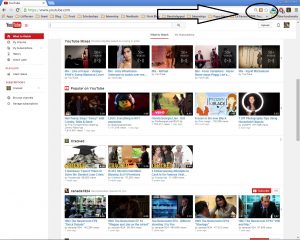

Not only can you look up at a specific website in their ever-growing database, you can also download a browser extension for the following browsers: Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, and Opera. The TOSDR Microsoft Explorer extension is still being developed. The extension works like this: After installation, you go to a website. If a website is in the TOSDR database an icon will appear in the upper right part of the screen inside of the browser, which will give the rating of the Terms of Service.

The rating will be a letter grade from “Class A” (very good) to a “Class E” (very bad) or a question mark, if TOSDR has not assigned a website a letter grade. From there, you can click on the grade, and TOSDR will also tell you what is good or bad about the website’s terms of service. Currently, these extensions do not work on mobile devices, although Opera is currently developing their operating system so the computer-based extensions will work on mobile devices.

As more and more libraries develop digital content and may start requiring logins, the website gives 24 topics for websites to consider when creating their own Terms of Service for online platforms. While there is no boiler-plate language, it does give preferred contractual positions for a user-focused Terms of Service agreement.

If you have strong opinions about the terms of service of a website, you can always submit content or review of a website’s terms of service, with the instructions available here: http://tosdr.org/get-involved.html or join their working group: https://groups.google.com/forum/?fromgroups#!forum/tosdr