I am a jazz fan, so Hugh Morton’s negatives of jazz musicians have interested me from the first time I saw them. Morton began photographing jazz musicians when he was in high school and he continued throughout his life. Clarinetist and bandleader Benny Goodman was his favorite musician. In 1988 Morton wrote in Making a Difference in North Carolina:

Illustrative of my loyalty to Benny Goodman, I saw him and his band in the ’30s and 40’s in Washington, D. C., Baltimore, Detroit, New York, and Raleigh, and in 1979 in Greensboro and 1983 in Wilmington. Each time I took pictures, and I deeply regret the cameras and film in the early days did not measure up. It was virtually impossible to snap candid shots that are up to today’s standards.

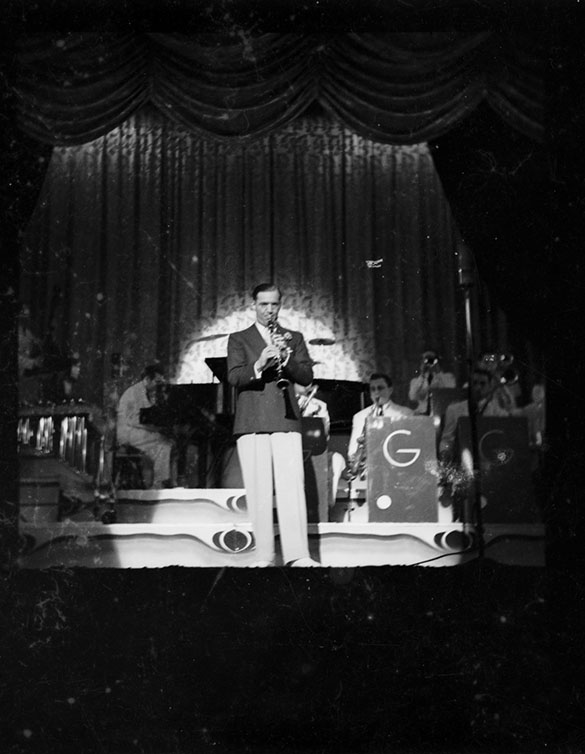

It may be better to contextualize that statement with a bit of clarification. I believe the camera technology was available, but perhaps not to a teenager. In 1937, Leica 35mm cameras had been available since 1925, so I don’t think that cameras were the issue. Morton photographed during this time with a camera that used the 127 film format, which is larger than the 135 format and its film cartridge that came to market in 1934. Black-and-white negative films during that time, however, did not have sufficient light sensitivity (film speed) to capture an image without blurring caused by shaking a hand-held camera set with the slower shutter speeds needed to get a proper exposure. Below is one of Morton’s negatives made at that Washington, D.C. concert . . .

. . . and here’s a cropped portion of the negative that illustrates softness from camera movement. (Look at the “G” on the music stand.)

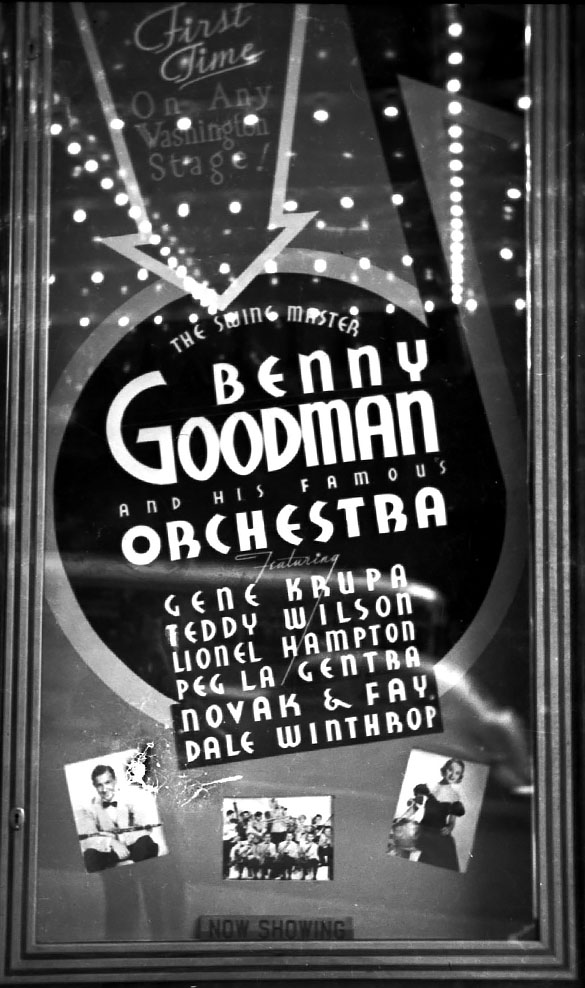

Until very recently, the location and date Morton made the marquee poster negative was unknown. A project I’m working on brought his jazz negatives to my attention, so I began to sort the Benny Goodman negatives into groups based upon the stage settings. Luckily the marquee poster exposure is on a negative strip that also has an interior view of Goodman performing inside the theatre, so that group of images with the stage seen above formed the Washington batch.

Next I spent some quality evening and weekend time digging around for clues that might lead to more information. For historical information I checked out the Music Library’s copy of Ross Firestone’s biography Swing, Swing, Swing: The Life and Times of Benny Goodman. (It was also a good excuse to borrow the 2-CD set Benny Goodman at Carnegie Hall, 1938 to listen to while researching!) But the definitive answer came from the University Libraries’ online catalog access to historical issues of The Washington Post. A search through that newspaper revealed where and when Morton made that group of negatives.

The Washington Post column “Nelson B. Bell About The Show Shops” for June 5, 1937 covered Goodman’s gig in an article with a long title that begins, “‘Kid Galahad’ and Benny Goodman Score at the Earle.” A bit more searching through other issues of the newspaper pinpointed that Goodmen and orchestra opened a one-week engagement at the Earle Theatre on June 3, 1937. Bell listed in his review the performers’ names in the exact order they are printed on the marquee poster. His list also revealed the proper spelling of the name Peg LaCentra (not Gentra, as in the poster). Bell also noted that he believed it was Goodman’s “first visit to a Washington stage,” which is very similar to the wording on the poster.

Firestone’s biography does not mention the Washington venue; it only states that the band left New York in the beginning of June destined for its third engagement at the Palomar Ballroom in Los Angeles at the end of the month. He noted that “aside from a few theater dates” the month was almost entirely one-nighters spread through Pennsylvania and several midwestern states. Firestone’s book does, however, provide some prior context. On March 3, just three months before the Earle Theatre performances, Goodman’s orchestra started a two-week engagement at the Paramount Theater on Times Square in New York City.

A sold-out crowd saw that opening night’s first performance “and the audience of restless youngsters was in unusually high spirits.” They greeted the orchestra, Firestone recounted, “with an ear-shattering roar of clapping and whistling and stomping and yelling that sounded, Benny remembered, ‘like Times Square on New Year’s Eve.’ ‘It was exciting, [Goodman] recalled, ‘but also a little frightening—scary.'”

Firestone vividly described the band’s performance, then wrote,

It was apparent to everyone . . . that something truly momentous had just taken place, that the Goodman orchestra’s brief forty-three-minute sojourn on the Paramount stage was some kind of breakthrough that topped, and was different from, all its previous successes. What started out as just another stage show had turned into a kind of celebration of the spirit, a love feast of communal frenzy that was, as Variety observed, “tradition-shattering in its spontaneity, its unanimity, its sincerity, its volume, in the childlike violence of its manifestations.”

Firestone then accounts for what he believed was the performance’s “stunningly obvious” cause. “The school kids were among Benny’s most zealous fans, and this was the first chance they had to hear him in person,” he wrote. Goodman’s usual New York venue was The Hotel Pennsylvania, which was “completely beyond the reach of the legions of ordinary youngsters who, up to now, could only listen to Benny on the radio or spring for an occasional record.” A multitude of kids had lined up starting before seven in the morning to buy a twenty-five cent ticket. By the end of the day, the Paramount has sold 21,000 admissions.