As is often the case with Hugh Morton photographs, a single image that seems straightforward enough turns out to have a more involved story. Such is the case with today’s post. Looking for any photographs made during the month of January led me to two sets of images: six color slides and six 120 format black-and-white negatives—and a larger story.

In 1921, the North Carolina legislature appropriated $75,000 for the construction of a new building for the Cherokee Indian Normal School of Robeson County. Completed in 1923, the building housed twelve classrooms, two offices, four toilets, a large auditorium that seated several hundred, and a “picture booth” on the upper floor. Though funded by a state appropriation, the building took on a symbolic link to the Lumbee community’s efforts to sustain the school from its origin as the Croatan Normal School that opened in 1887. Over the course of time, the building became known as “Old Main.” Local newspaper accounts in which the name starts to appear suggest around 1952, but perhaps even sooner after the addition of two new buildings, Sampson Hall and Locklear Hall, in 1949 and 1950.

Reflecting the Lumbee’s complex history, the school experienced many name changes during the 20th Century: first, in 1911, the Indian Normal School of Robeson County, and then in 1913, the Cherokee Indian Normal School of Robeson County, which it retained until 1941 when it became Pembroke State College for Indians. In 1949 the name was shortened to Pembroke State College, and then Pembroke State University in 1971. In October of that year, the North Carolina General Assembly passed legislation that enlarged the statewide university system to include all four-year state-supported institutions of higher education. Thus Pembroke State University became part of the University of North Carolina system effective July 1972.

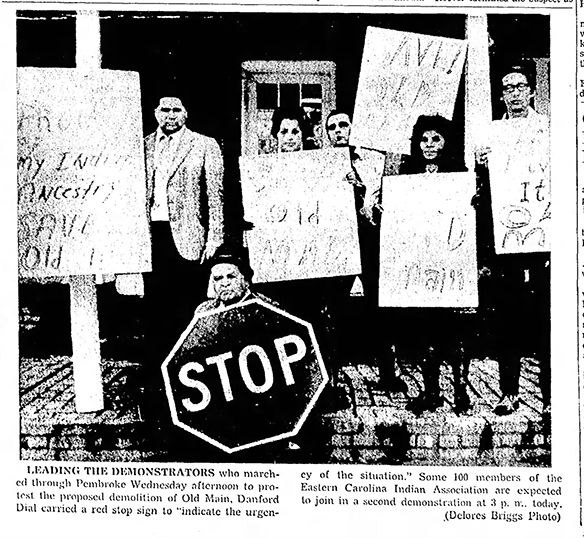

In July 1970, Old Main stood in disrepair. The university included in its capital improvement requests to the Advisory Budget Committee, as a priority, a replacement auditorium to cost $1.6 million. Approved in January 1971, Old Main became earmarked for demolition. A petition drive led by Daniel Dial to spare the building, however, gathered 1,000 Lumbee signatures by mid December 1971. Dial told a news reporter for The Robesonian, “People sign it weeping. People want to sign it, beg to sign it.” The petition’s wording was:

Let us preserve our heritage and our legacy. OLD MAIN on the Campus of Pembroke State University is the last monument to our humble yet very historic beginning, Historic buildings are preserved all over this land and we should show this much concern for ours. We are a proud people and OLD MAIN has helped keep us so. Please sign this sheet to show your loyalty.”

Dial anticipated the collection of 10,000 signatures. The effort drew national attention.

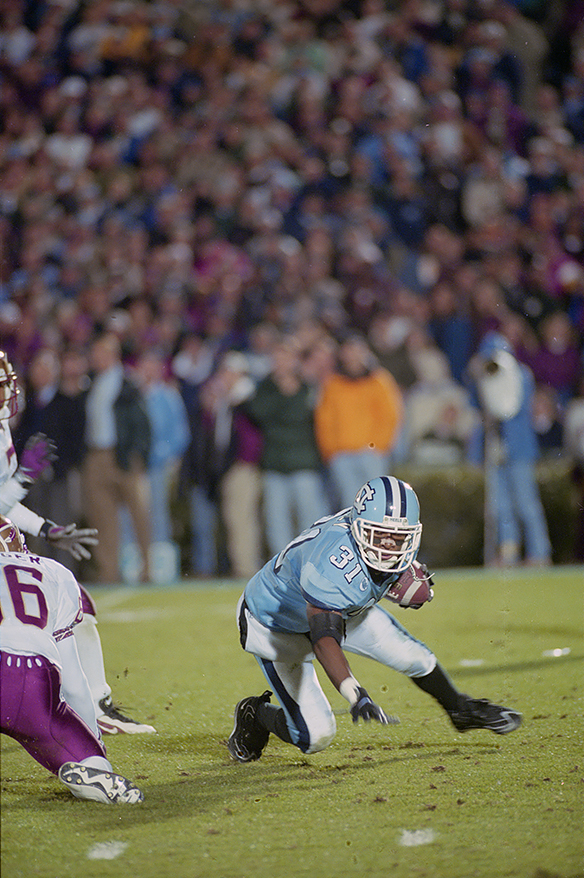

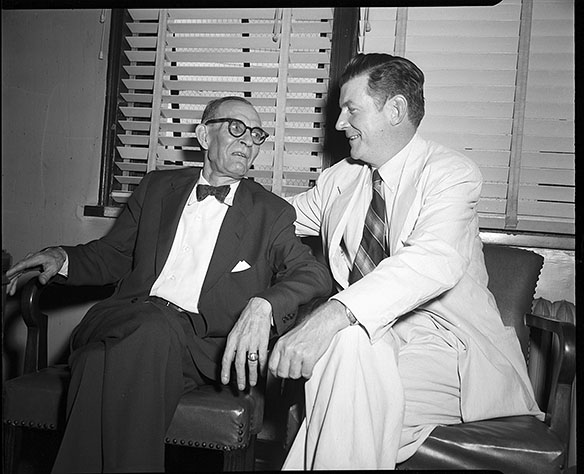

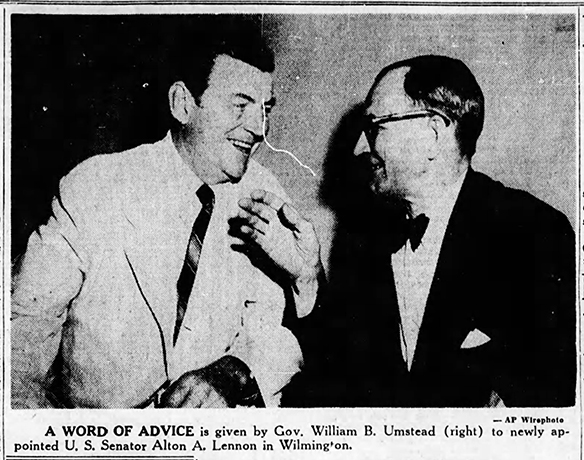

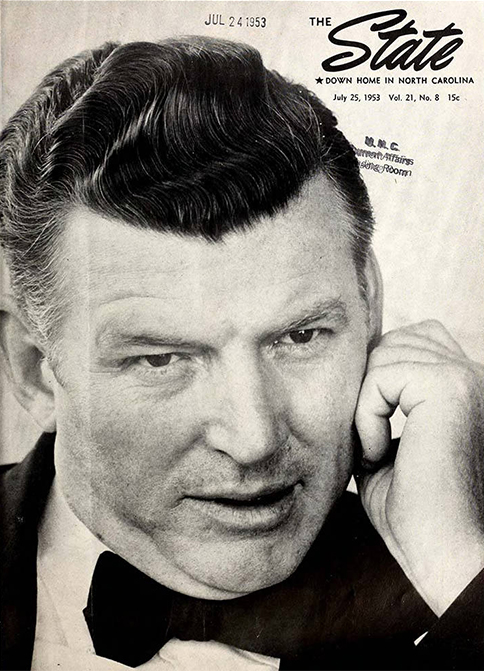

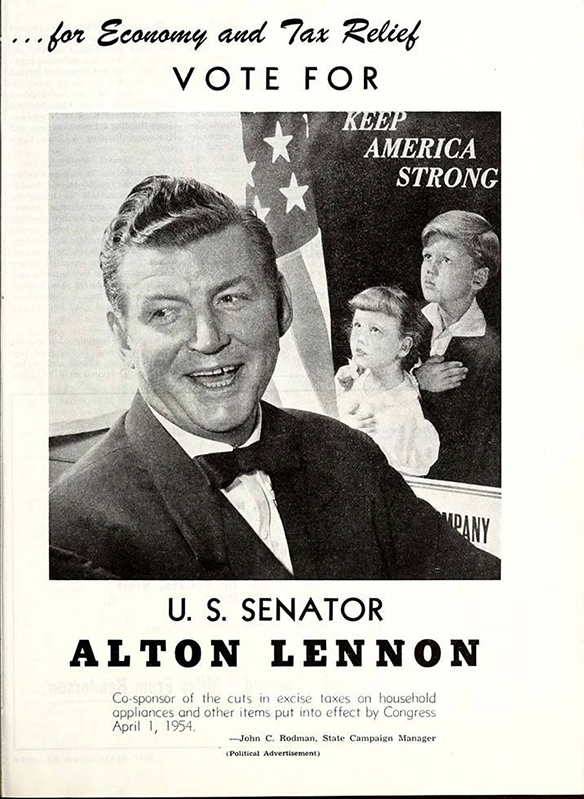

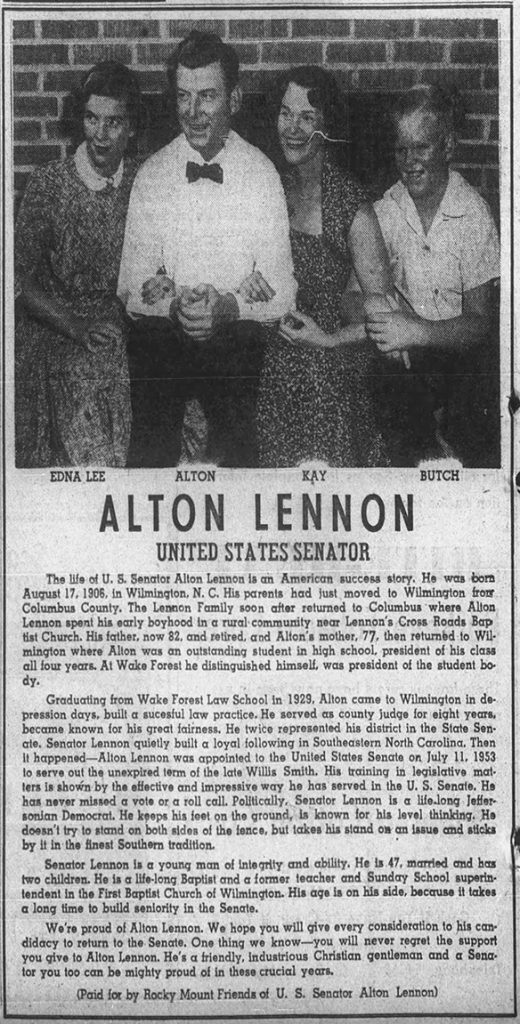

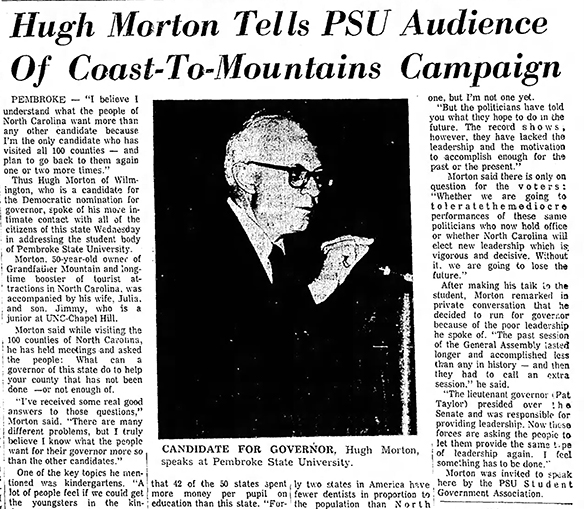

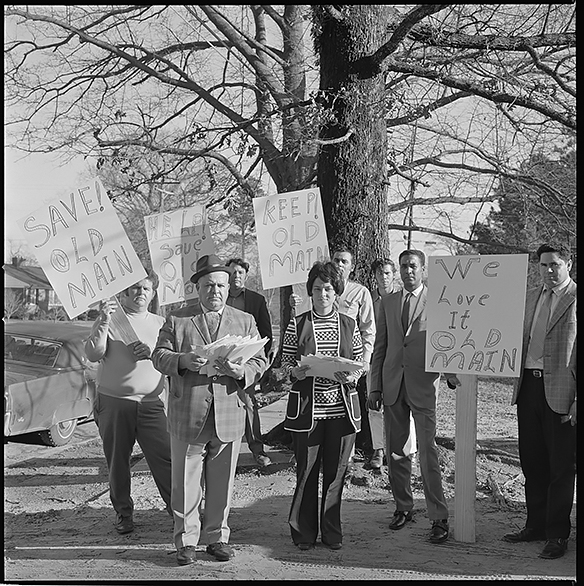

On Wednesday, January 12, 1972, about two dozen people carried protest signs in front of the building, chanting “Save—Old—Main.” Inside, Hugh Morton gave a noontime campaign speech at the invitation of the Student Governance Association. Morton had officially entered the Democratic Party’s gubernatorial primary race six weeks earlier on December 1.

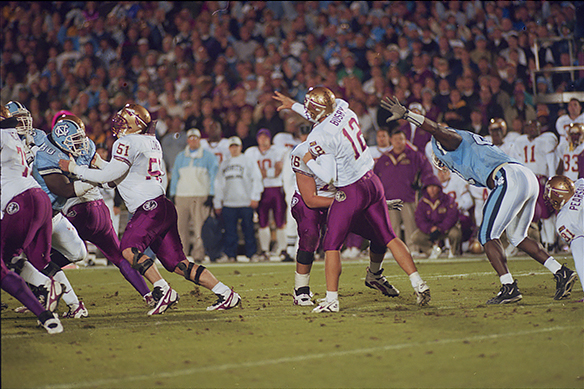

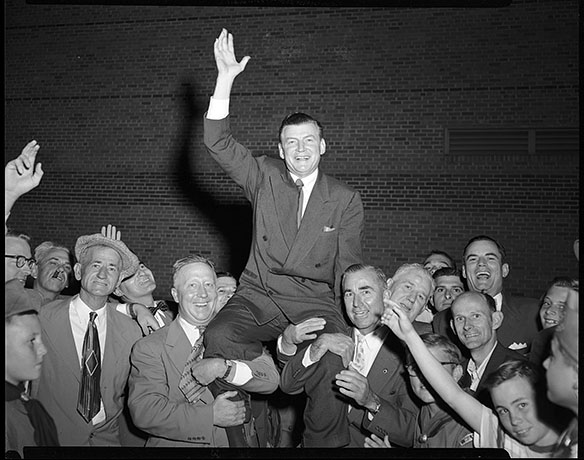

On that Wednesday evening, Danford Dial met with the Pembroke Jaycees “to discuss what constructive plans can be made for the preservation of Old Main building on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. By that time, The Robesonian reported, Dial had obtained signatures from “some 7,000” supporters who favored keeping the building in lieu of the proposed demolition. Dial noted that demonstrations would continue and would be “on a much larger scale.” The Robesonian‘s coverage from this period suggests January 12 may have been the first day of demonstrations. The newspaper caption for the group photograph above states, “Some 100 members of the Eastern Carolina Indian Association are expected to join in a second demonstration at 3 p. m. today.” In less than two weeks, the topic became part of the statewide political fray. Come May, Shirley Chisholm would visit the campus as part of her presidential campaign and speak from the steps of Old Main.

I’m not a politician. I’m trying to be one, but I’m not one yet.

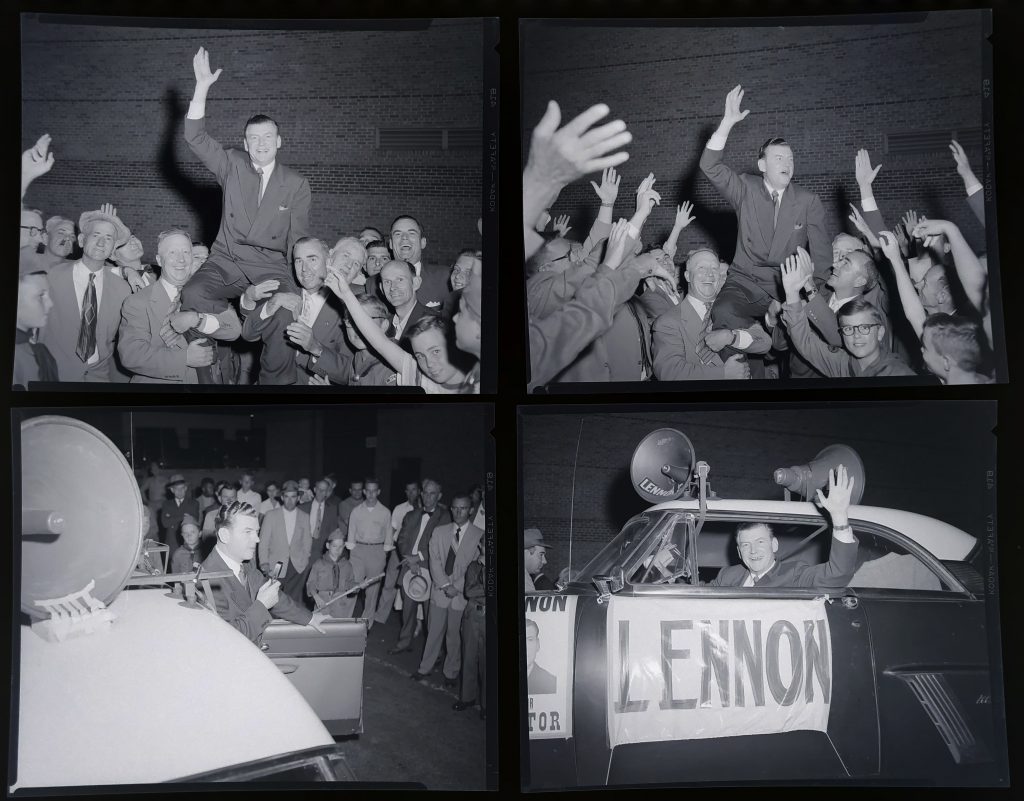

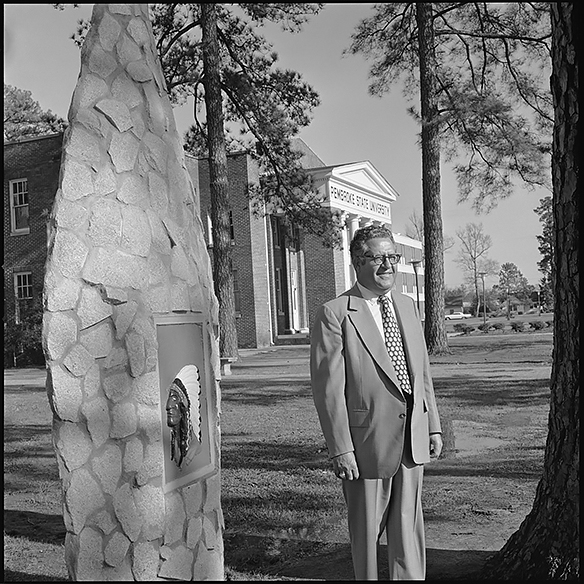

Morton stated during his campaign speech that he was not yet a politician, but that he was trying to be one. He certainly was a photographer, and as you would expect Morton made several exposures outside Old Main. Surviving in the collection are six black-and-white 120 format negatives and six 35mm color slides. If my extrapolation from the photographic caption text published in the January 13th issue of The Robesonian is correct—that is, the second demonstration would be happening “today,” thus making the previous day’s demonstration on the 12th the first demonstration—then Hugh Morton captured scenes of the first day of the Save Old Main demonstrations on film, both in color and in black-and-white.

Four of the color images are already in the online collection of Morton photographs. The two that are not online are variant views of Old Main; the black-and-white images, however, have not been viewable online before this blog post.

In addition to the two black-and-white negatives shown above (but not shown here), Morton photographed himself with Dr. English E. Jones, president and then chancellor of the university from 1962 to 1979. He also photographed Jones alone twice, as he did in color (one of which is in the online collection). The sixth black-and-white is a variant of the above group of demonstrators.

On January 27, The Robesonian published a statement issued to the newspaper by Morton:

I feel the same about the Old Main building as I do about the governor’s mansion. If it is practical and feasible to save it and make it useful, I would certainly like to see it preserved. I don’t personally know enough about its current condition to know the answer.

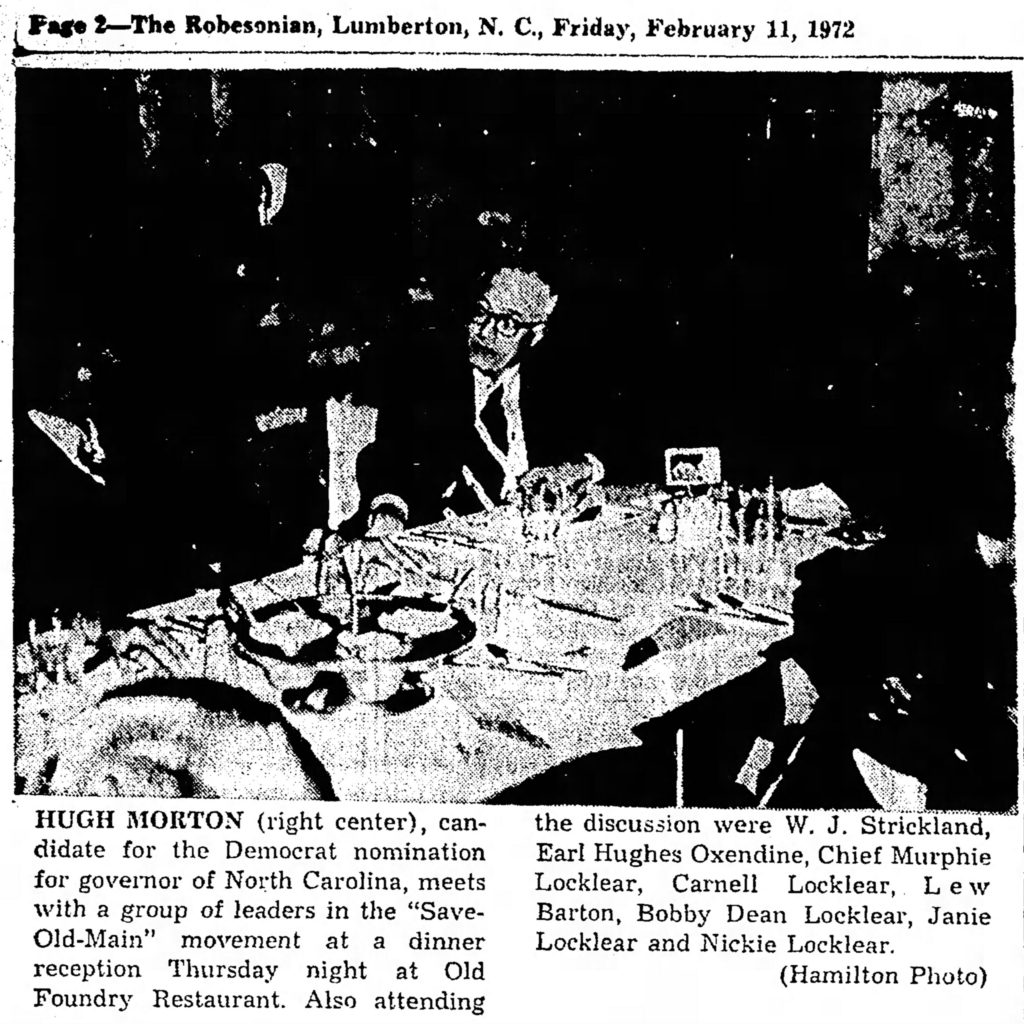

Morton also stated that he had not been invited to speak again to students at Pembroke, but would be glad to do so if asked. He also noted that he planned to visit Lumberton two or three more times. Two weeks later on February 10, 1972 Morton met with a group of Save Old Main leaders at the Old Foundry Restaurant. The Robesonian news story on February 11 about his visit quoted a Morton statement, which reads as an enhancement and refinement of his earlier statement:

Old Main is very much in the same category as the governor’s mansion. It is a beautiful and beloved building which should be preserved if it is at all possible. I hope that an alternative site can be obtained for the proposed new building in order that further architectural investigation can be made into the feasibility of saving and utilizing Old Main.

A week later, Morton withdrew from the political race. The preservation race to save Old Main, however, continued. In July the university’s board of trustees approved relocation of the new auditorium to a parcel of land previously condemned. On March 18, 1973, an arsonist set Old Maid ablaze—a potential major setback that actually turned the tide in the building’s favor. Governor James Holshouser went to the campus that evening and pledged his support to restore Old Main. A year later a restoration plan was in hand. In 1976, the building gained acceptance onto the National Register of Historic Places. Old Main, completely rebuilt, reopened in 1979. Currently it is home to several occupants, including the Museum of the Southeast American Indian, the Department of American Indian Studies, and the student newspaper, The Pine Needle.