When faced with a problem for which the solution cannot be reached with the resources on-hand, there are two options: outsource the job or acquire the necessary resources to do it yourself. Ah . . . the makings of today’s (long) blog post!

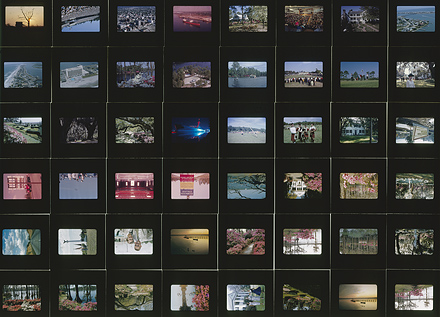

There aren’t too many places “out there” that can scan vast quantities of slides. One company I know that does is a vendor I met a few years ago at a professional conference. I called them to see what services they could provide for scanning 200,000 slides. We talked through the project in the largest and broadest sense. They kindly agreed to investigate what such an undertaking might cost in a non-binding estimate. We sought price estimates based upon two parameters: scans measuring 3,000 and 4,000 pixels “on the long side.” When archivists talk about the number of pixels on the long side, we are addressing the quality of the scan necessary to met a certain standard. So we need to digress for a bit to explain those standards.

Both the 3,000 and 4,000 figures appear in the United States National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) report, Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Masters for Electronic Access: Creation of Production Master Files—Raster Images. We turned to this document a few years ago when trying to determine the level of quality we wanted to attain for the scans we provide to researchers who request reproductions from original material in the photographic archives. So before we proceed, a sidebar is needed in order to explain two important terms in NARA’s mouthful of a title: “production masters” and “raster images.”

At the risk of over-simplification—more details on this topic can be found readily on the Web—a raster image is one that has been created by scanning an analog image from side to side, top to bottom and then representing the image as rows of dots. With computer monitors, those dots are pixels (“picture elements”) and the number of those pixels per line relates to image resolution: the more pixels that represent the image, the higher its resolution.

“Production master” is a term used by NARA to describe raster image files “used for the creation of additional derivative files for distribution and/or display via a monitor and for reproduction purposes via hardcopy output at a range of sizes using a variety of printing devices.” In short, files meant to be used for access and reproduction. The important inherent distinction this definition makes is that the files are not “preservation masters.” Preservation masters are image files serving as surrogates meant to replace the original item.

Warning: math ahead!

The NARA guidelines for 35mm recommends 4,000 pixels across the longest dimension of the negative or slide, with 3,000 pixels as its “Alternative Minimum.” A 35mm negative is approximately 1 7/16 inches long, so 4,000 pixels divided by 1.4375 inches equals 2783 pixels per inch (ppi); lowered to 3,000 pixels, the ppi drops to 2,087. So using round figures, a production master from a 35mm negative or slide should have a resolution of 2,800 ppi, but no less than 2,100 ppi. By comparison, the Nikon Coolscan, which scans at 4,000 pixels per inch, produces scans in the neighborhood of 5,750 pixels on the long dimension.

But why is 4,000 pixels the benchmark? Well, I’ll spare you a double dose of math and say that 2,800 ppi resolution produces a good quality 8 x 10-inch inkjet print. The 8 x 10-inch photographic print was the de facto standard used by publishers before the digital imaging age, and NARA designed their guidelines to meet that equivalency.

(End of side bar).

The vendor estimated that their throughput at the 3,000-pixels specification, based upon prior experience, would be 125 scans per hour. That would be 5,000 slides a week or 200,000 slides in 40 weeks. Now that is a workable time frame! The cost, however, was not workable despite having significant funding available. Their charge was very reasonable per item, but the cost still came in at six figures—not too surprising, in retrospect, when you have 200,000 items. In summary, outsourcing a slide scanning project may be better suited to collections that are sizable but not nearly with the magnitude of Morton, or to institutions that do not have a viable, in fact burgeoning, digital library operation in place such as the UNC Library.

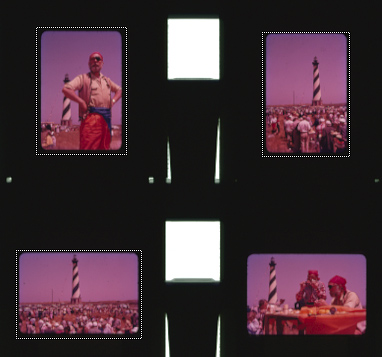

A question emerged in these deliberations. What equipment does that vendor have on-hand that enables it to achieve that level of throughput? They utilize Kodak’s Professional HR 500 film scanners paired with Halse slide carriers. Kodak made three industrial-level scanners for the professional photo lab marketplace. The HR 500 and its successor the HR 500 Plus handle roll film up to the 120 format (2 1/4 inches wide). Their sibling, the HR Universal, handles both roll films and sheet film up to 4 x 5 inches. The Halse carrier is designed to load slides into the scanner using the common Kodak Carousel slide tray that holds 80 slides.

The catch? (Isn’t there always something?!?!) Kodak discontinued manufacture of the scanners in October 2005 because, in their words, “with the decline in film capture, Pro Labs, in general, now have sufficient high-resolution productive scanning capacity.” In other words, professional photographers who used to shoot slides and color transparencies and then have them scanned by pro labs are now shooting all digital. Photographic archives, where many of those slides and negatives have or will end up, do not constitute a large enough market to warrant their continued production.

So, now what?

Some Web searching fortunately led to an alternative source—there is a market for used professional machines and a broker who focuses on finding new homes for unwanted HR scanners. One buyer was Yale University’s ITS Media Services unit. An email to Joseph Szaszfai, manager of Photographic and Digital Imaging Services, and an ensuing phone conversation yielded very positive information with kudos such as, “There’s nothing equal to it.” Using two scanners, Yale generates 80 30MB files per hour per machine. At Yale’s production rate, 200,000 slides could be completed in 62.5 weeks. Again, impressive throughput. So impressive that we are looking to get one!