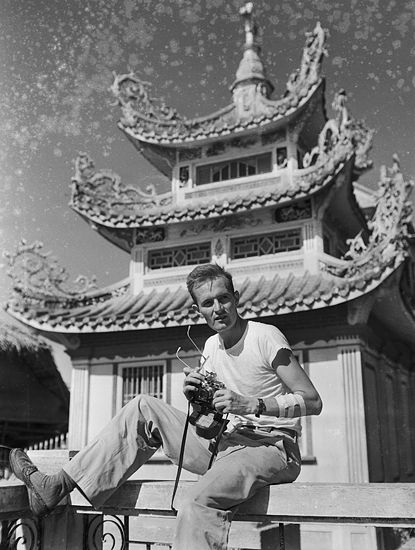

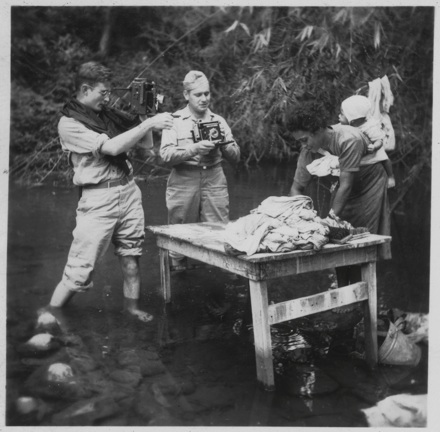

Hugh Morton with camera, Manila Chinese Cemetery, Philppines, circa March 1945.

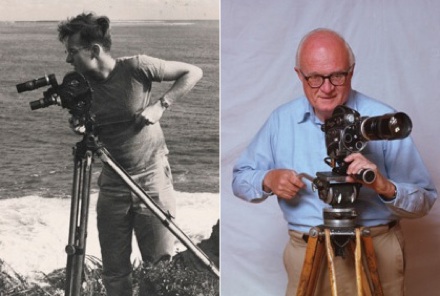

During the Memorial Day weekend, I looked online through the numerous photographs made by Hugh Morton during his tour of duty in the South Pacific during World War II as a photographer (still and moving image) with the United States Army 161st Signal Photographic Company. The idea was to have a military post related to the holiday. I must confess that the exercise consumed the greater portion of my holiday weekend, but it was enjoyable and educational! It also was rewarding because my journey through the collection, using the geographical subject heading “Islands of the Pacific,” led to several corrections with some interesting new identifications. Unfortunately it has taken some time to update the catalog records, plus some of the master scans were “M. I. A.” so I needed to rescan those negatives. That extra work meant that this post got pushed into June—and there’s enough material to merit more than one post.

The delay turns out not to be a such bad thing, however, because significant events in the war in the South Pacific took place during the month of June 1945—particularly on Luzon that lead to the liberation of the Philippines, declared on July 5th. Ironically it was through that country’s two national heroes from the Spanish-American War—Andrés Bonifacio, and José Rizal—that I was able to identify the actual locations depicted several photographs.

Our first stop on this virtual expedition, however, is 4,000 miles southeast of Manila: Nouméa, New Caledonia.

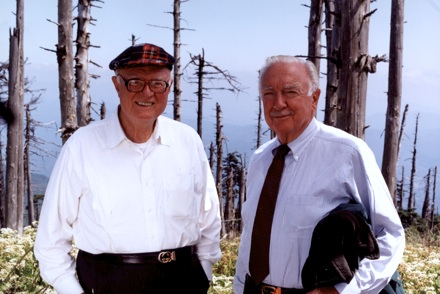

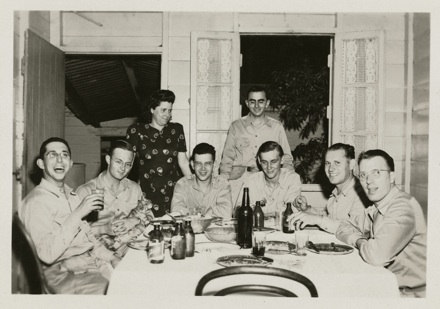

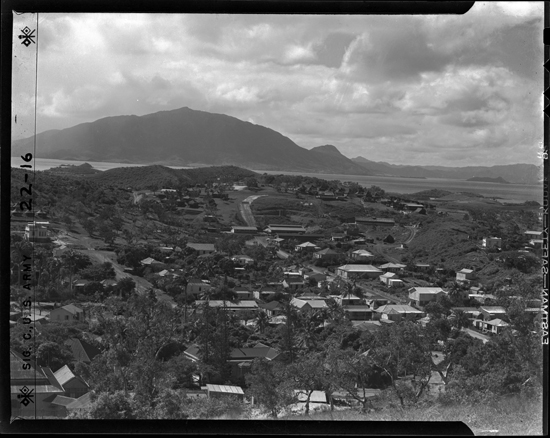

Nouméa with Mount Dore in the distance, New Caledonia, circa late 1943–1944.

Many of the “misidentified” images are from a batch of negatives that Morton originally labeled “Noumea, New Caledonia.” Nouméa is the capitol of New Caledonia, a country formed from a group of islands that are more than 900 miles east of Australia. Nouméa is located on the southwestern coast near the southern tip of a long slender island called Grande Terre and situated on a protected harbor with a small island, Ile Nou, just offshore. In 1942 the Allies needed to relocate the center of their Pacific operations from Auckland, New Zealand to a place closer to the “front.” New Caledonia had been a French colony since the mid 19th century, and Nouméa was significantly closer to the action. During the summer and autumn of 1942, the United States Navy and Army constructed extensive facilities at Nouméa, and on 8 November 1942 Nouméa became the official headquarters of the Allied Commander of the South Pacific. New Caledonia also became home to many USO performances by Bob Hope and others, which Morton photographed in 1944.

When the army shipped members of the 161st Army Signal Corp to the Pacific, including Hugh Morton sometime in late 1943 or early 1944, they likely landed first in Nouméa. Above is a scenic photograph by Morton of Nouméa with Mount Dore in the distance, scanned from the original negative with a U.S. Army Signal Corp identification number 22-16 along the left-hand edge. Another scan in the online collection is from a cropped print. The snapshot photograph below, with Saint Joseph’s Cathedral in the background, is the only other positively identified view made Nouméa. The original 2.5 x 3.5-inch negative is in the Morton collection, but it has not been scanned.

So far, these are the only two images positively identified as Nouméa. When Elizabeth Hull processed World War II material in the Morton collection, she made a note in the finding aid alerting users that many of the images in that the batch of negatives may not be of Nouméa. Many of those negatives can now be assigned their proper place on the map: the Philippines, where Morton’s military service concluded in the spring of 1945. The next post (or posts) on this trip back to the South Pacific will be a reflection of Morton’s tour of duty: “island hopping” our way to the Philippines.