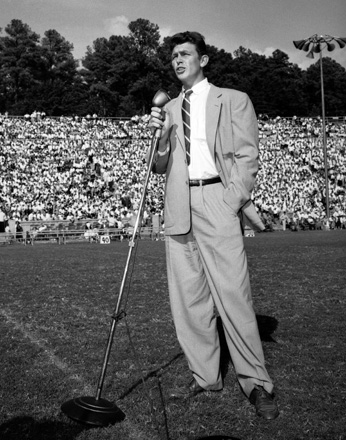

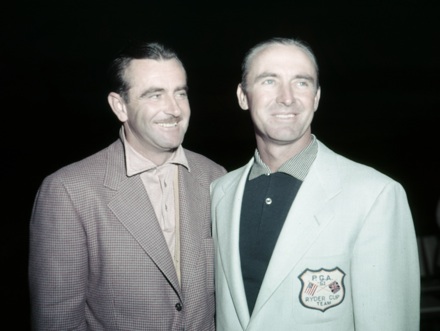

Given a certain recent historic election, it seems quite timely to highlight another that undoubtedly helped pave the way — the 1969 election of Howard Lee (on right, above) as the first black mayor of a predominantly white southern town since Reconstruction.

As the Daily Tar Heel reports, Lee has recently released a new memoir entitled The Courage to Lead: One Man’s Journey in Public Service, in which he describes the blatant discrimination he faced while campaigning in the South, e.g., being barred from from addressing white audiences. Certainly a different political climate than the one in which Barack Obama has risen, though there are some similarities in the grassroots nature of their campaigns.

From what I’ve seen so far, there are only a few photos of Lee in the Morton collection, such as the one above, in which he is pictured with Agriculture Commissioner Jim Graham (L) and Congressman L. H. Fountain (center). Does anyone know what event this is? Why are some people wearing leis?

Lee’s 1969 campaign is heavily featured in the Billy Ebert Barnes Collection held by the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives. (A digital collection of a selection of Barnes’s photographs is available, but because the Howard Lee photos are not part of his North Carolina Fund images, they are not represented online yet. Keep your eyes out for them!)

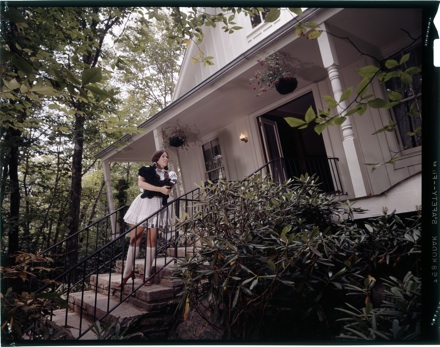

A small portion of the NCC Gallery’s current exhibit, “Soapboxes and Treestumps: Political Campaigning in NC,” is also devoted to Lee. The image below (a Billy Barnes photo) and text are drawn from that exhibit. Visit the Gallery to see the rest!

“Lee moved to Chapel Hill in 1964 to attend graduate school at the University of North Carolina. When he and his wife moved into the Colony Woods neighborhood, he found that many whites in the area were still uncomfortable living near blacks. He received harassing phone calls and a cross was burned on his lawn. These experiences encouraged him to become involved in local politics. Lee ran in and won the mayoral election over his opponent Chapel Hill Alderman Roland Giduz.

Lee’s campaign was successful because he generated support at the grassroots level. One of his supporters owned a Greyhound bus and drove voters to the polls, which resulted in a record turnout for Chapel Hill’s African American voters. Newspapers around the world covered the historic race, and both Newsweek and Time ran profiles on the the new mayor.

Lee ran unsuccessful campaigns for U.S. Congress in 1972 and lieutenant governor in 1976. He served in the state senate from 1990 to 1994 and from 1996 to 2002. In 2003 he became the first African American elected as chair of the North Carolina Board of Education.”