Arthur Smith passed away one year ago today. At the time, I hurriedly started a V2H blog post to mark the occasion. As I worked on it I kept finding more and more interesting material . . . and April 3rd slipped farther and farther into the distance before I just could wrap it up. It’s been sitting in the unpublished drafts section of the blog ever since. Then a week or so ago, volunteer Jack Hilliard sent me post about Arthur Smith for use today. After I finished working on Jack’s piece I dusted off this post, cleaned it up, and published it today even though it could use some more work. The result? A twin bill! This post is mine; the “special connection” post is Jack’s. We hope you enjoy today’s double feature.

For many, if not most, Arthur Smith may not be a household name. Have you seen Deliverance—or played an “air banjo” version of the well-known version called “Dueling Banjos” from the memorable scene in that 1972 movie? If so, then you have a piece of Arthur Smith in the fiber of your being because Smith is the original writer of that song, which he played and recorded with Don Reno as “Fuedin’ Banjos” in 1955.

Arthur Smith was born in Clinton, South Carolina in 1921. The 1930 United States Census enumerated his family in Flat Creek Township in Lancaster County on April 4th, just a few days after Arthur’s 9th birthday. He is the son of Clayton S. Smith and his wife Viola Fields, both North Carolinians by birth. In the 1930 census Arthur had two older and two younger siblings: Ethel, age 13; Oscar, 9; Ruby, 7; and Ralph, 6. Clayton’s occupation is listed as a weaver in a cotton mill.

The most likely matching “Arthur Smith” in the 1940 census shows Arthur as one of three lodgers at home of what looks like Dixon G. and Sybil Stewart (the census taker’s handwriting is difficult to read) at 442 Kennedy Street in Spartanburg, S.C. Stewart and the lodgers all have their occupation listed as “Advertise” and written (again hard to decipher) in the Industry column is “Radio” and what looks like “Vine Herb.” This is a nugget for a future researcher to resolve.

*****

Arthur Smith was already an accomplished musician well before “Fuedin’ Banjos.” When Smith was in eighth grade, he and brothers Ralph and Sonny formed a Dixieland jazz band called The Arthur Smith Quartet. At the beginning their financial prospects were bleak. Smith said during an interview with Don Rhodes for his article “Arthur Smith: a Wide & Varied Musical Career” in the July 1977 issue of Bluegrass Unlimited,

We nearly starved to death until one day we changed our style. We had been doing a daily radio show in Spartanburg, South Carolina, as the “Arthur Smith Quartet.” One Friday morning we threw down our trumpet, clarinet, and trombone and picked up the fiddle, accordion, and guitar. The next Monday we came back on the radio program as “Arthur Smith and the Carolina Crackerjacks.” My brother, Sonny, came up with the name. The Carolina was because we were from South Carolina, and the Crackerjack part came when Sonny found that the word according to the dictionary meant one who is tops in his field.

This would probably be as good a place as any in this story to state that there is no definitive biography about Arthur Smith, and much of what is on the Internet or in print is anecdotal, sketchy or brief, and with a fair amount of rehashing of what someone else had already written. Pulling this post together has been a bit of a challenge, so please leave a comment with corrections or clarifications.

When Arthur Smith was in tenth grade, the group made their first recording during a field recording session for RCA Victor in 1938. According to one discography, the recording date was 26 September 1938 at the Andrew Jackson Hotel in Rock Hill, S. C. Smith recalled in the booklet The Charlotte Country Music Story, that their best song from that session was “Going Back to Old Carolina” (Bluebird Records recording B-8304).

Smith must have paid attention to the school books, too, because he was the class’s valedictorian. Smith had an opportunity to attend the United States Naval Academy after graduation, but he declined because he knew he wanted to be a musician.

*****

The band’s success grew and at some point in time, possibly 1941, Smith moved to Charlotte when he and the Crackerjacks became regularly featured on WBT’s country music radio programs, among them probably Carolina Barndance.

As with most born in this era, however, WWII brought disruption and the Crackerjacks disbanded. All three brothers served in the military, Arthur Smith in the Navy. He played in his military band, and it was there that he wrote “Guitar Boogie,” his breakthrough recording that sold more than a million copies in 1945. After the war, the Smith revived the Crackerjacks.

*****

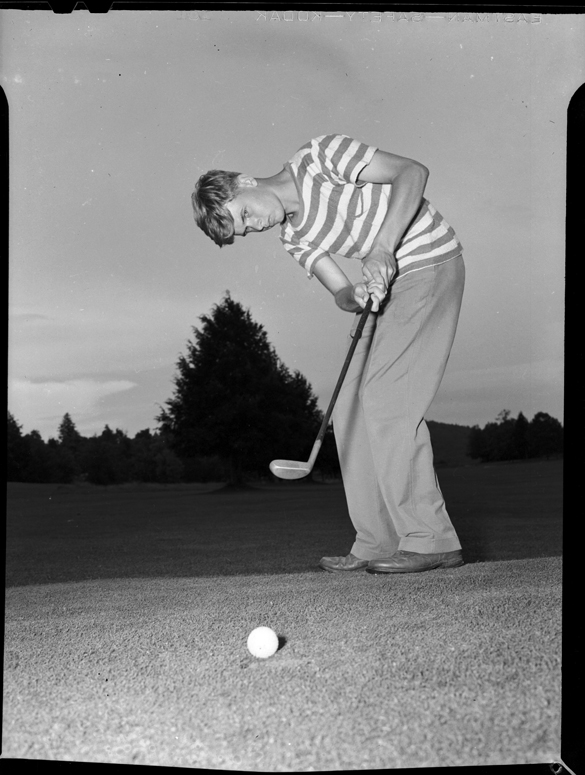

I’ve not found mention of how Hugh Morton and Arthur Smith met, but I hope those that might know will comment below. Morton photographed Smith with and without the Cracker-Jacks (that variant spelling, with and without a hyphen, was often used) on several occasions over many years. Both were born in 1921, and both served in the military during World War II; Morton as a photographer and cameraman in the United States Army 161st Signal Corps, Smith in the United States Navy. The photograph at the top of this post dates from 1952, used to promote the Azelea Festival in Wilmington that year.

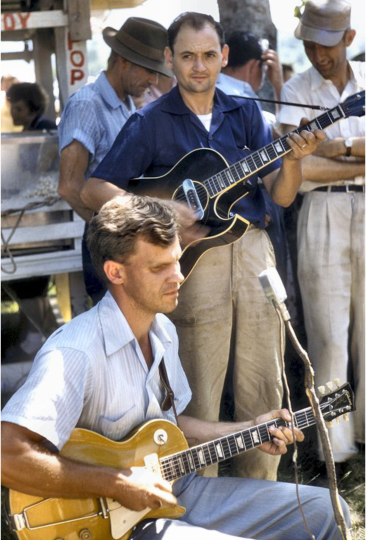

Smith and Morton may have met earlier, however, at Singing at the Mountain in 1950. In his book with Edward Rankin, Making a Difference in North Carolina, published in 1988, Hugh Morton recalled that it was around 1950 that Singing on the Mountain had a “big boost” in attendance. Singing’s co-founder Joe L. Hartley soon thereafter gave Smith the designation “Music Master” for the annual event because Smith “played a major role in inviting other outstanding musical groups.” Singing on the Mountain was already growing crowds prior to 1950. A brief article about the 1949 “Singing” published in the Watauga Democrat noted that 25,000 people had attended, the largest crowd to date. The following year, an article in the 29 June 1950 issue of the Wautaga Democrat about that year’s singing described the previous Sunday’s event: “One of the musical highlights during the beautiful summer day was provided by Hillbilly Headliner Arthur Smith and his Crackerjacks from Columbia Broadcasting System and Radio Station WBT, Charlotte. . . . Highway patrolmen reported that during one period around noon, the highways leading to this convention were crowded by cars bumper to bumper, stretching four miles in one direction and three in the other.”

Morton wrote in Sixty Years with a Camera,

Arthur Smith is one of my dear friends, and for thirty consecutive years he was the singing master for “Singing on the Mountain” at Grandfather. He of course wrote the Number 1 banjo song in the world, “Duelling Banjos,” [sic] and the Number 1 guitar piece “Guitar Boogie.” He is also a very religious man, and he plugged the daylights out of the “Singing” and brought big crowds. Mr. Joe Hartley, the founder and chairman of the annual event, thought that his homemade sign out on the highway attracted the people. He never did understand that Arthur Smith’s promotion of the program on television was the reason for the huge crowds.

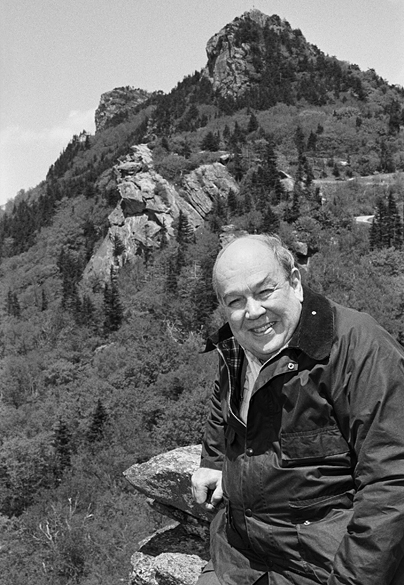

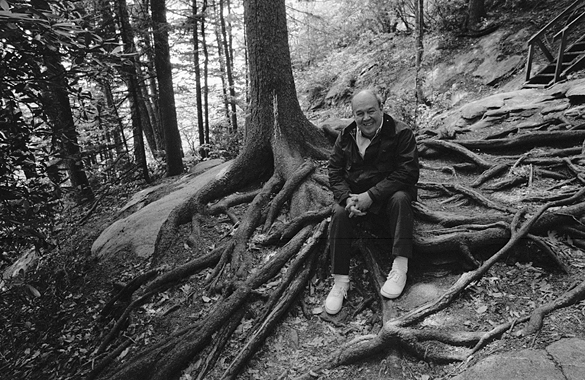

The next two photographs below may not have been published before this post.

*****

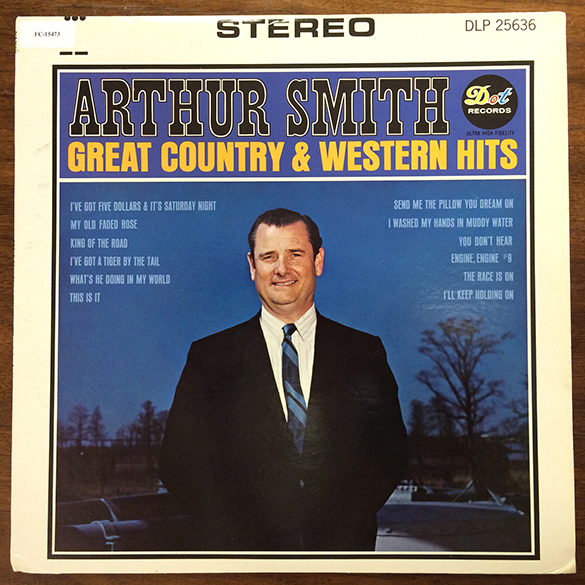

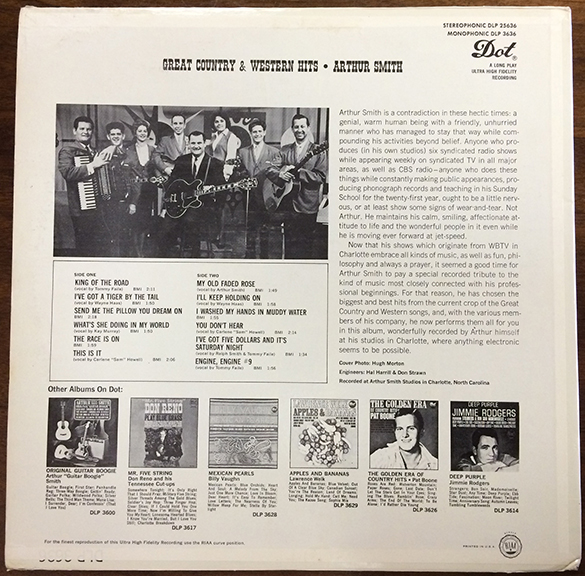

Hugh Morton photographed Smith on numerous occasions, including many made for record album dust jackets. Notice the photography credit for Hugh Morton on back of the following album’s cover . . .

Hugh Morton may be the photographer for Smith’s LP album The Guitars of “Guitar Boogie” Smith published by Starday Records in 1968. There is a 4″ x 5″ color transparency in the Morton collection that is an extremely similar pose to that on the album. Smith moved his hands slightly but his facial expression looks to be identical. I prefer the hand positioning in the one not used on the cover because his right hand is concealed.

Interestingly, CMT used a tightly cropped pose from this sitting in its obituary of Smith. The image source is Getty Images.

There’s a lot more Arthur Smith images to parse through in the Morton Collection, more than can be featured in this post. Needless to say, when someone writes the definitive biography of Arthur Smith. the Hugh Morton collection is a “go to” collection for visual research.

*****

ANY RELATION? The 1940 United States Census enumerated a James Arthur Smith, age ten months, living with his family on Florida Street in Clinton, Laurens County, South Carolina. James Arthur was the second son of Broadus E. and Annie Mae Smith. He had an older brother Edward, age 4 years old. The census taker’s handwriting for his father’s name is hard to decipher, but a Google search revealed a Broadus E. Smith who wrote four church hymns. Is this is likely connection. Broadus’s occupation is listed as a carpenter in the building construction industry.