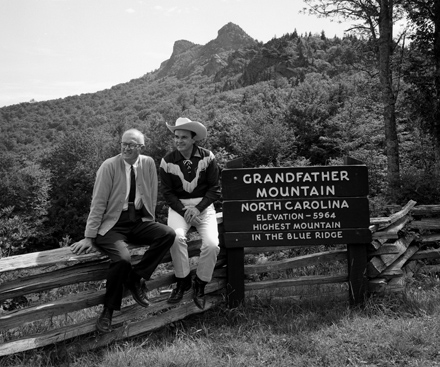

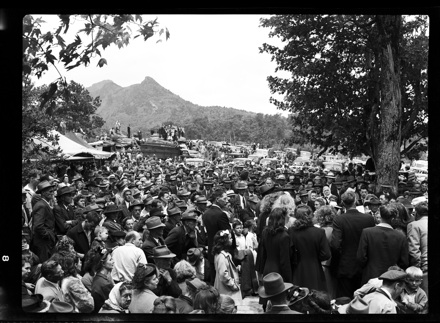

This coming Sunday marks the 84th “Singing on the Mountain,” the gospel convention held annually at the base of Grandfather that over the years has featured such well-known personalities as Johnny Cash and the Reverend Billy Graham. As you may have gleaned from my earlier post on Happy John Coffey, Hugh Morton’s photos from “the Sing” are some of my very favorite in the collection.

The early images (from the 1940s-50s) are especially striking—beautiful, black-and-white portraits of old time mountain musicians and preachers that are so evocative of a particular time, place and culture. I just wish I knew more about the performers, speakers and attendees of the Sing. (Shouldn’t somebody write a book? I’ve got illustrations for you!)

The image above came in an envelope labeled as follows:

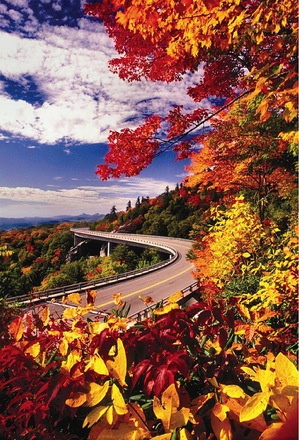

SINGING ON THE MOUNTAIN: Crowd shots, Grandfather Mountain in background. Significant fact of location at Grandfather of the Sing is that the mountaineers hold the mountain in high regard kin to worship. It is ‘The Mountain’ as far as they are concerned, because it is likely the most rugged in the East. The mountain folks get a feeling of altitude on it since Grandfather juts right up into nowhere with no other comparable mountains nearby to dwarf it. It’s [sic] altitude is 5964, which is 600 less than Mitchell, but Mitchell and others taller are rolling mountains with tall ones near, not jagged rock like Grandfather.

Can anyone help with identifications for the following two images?

The image below (which I love) shows Joe Lee Hartley, founder and longtime Chairman of the Sing, with an unidentified tiny performer. (This is a cropped version of the original). The poem below that (first and last stanzas only) was written by Hartley and appears in his “History of the Great Singing on the Mountain,” a circa 1949 pamphlet held by the North Carolina Collection.

Morning on the Grandfather Mountain

Composed by J. L. Hartley, Linville, NC

Morning on the Mountain

And the wind is blowing free

Then it is ours just for the breathing.

No more stuffy cities where we have to pay to breathe

Where the helpless creatures move and throng and strive to breathe.

Lonesome—well I guess not

I have been lonesome in the towns

Yes the wind is blowing free

So just come up into God’s beautiful country—

Get a breath and see.

![[Azalea] Vaseyi [on Grandfather Mountain], 1955](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/p081_ntbs4_000134_01.jpg)

![Rare Bats [on Grandfather Mountain], Spring 1984](https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/morton/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2008/05/bats.jpg)