The handwritten label — “Original Leyte” — on the negative envelope immediately caught my eye. It was the second envelope in the box, just after the envelope labeled “Fort Benning.” Leyte, an island in the Philippines, might possibly have a connection to Hugh Morton, who served as a photographer and film cameraman in the United States Army’s 161st Signal Photographic Company. Morton’s tour of duty ended in the Philippines after being injured by an explosion near Balete Pass on the island of Luzon.

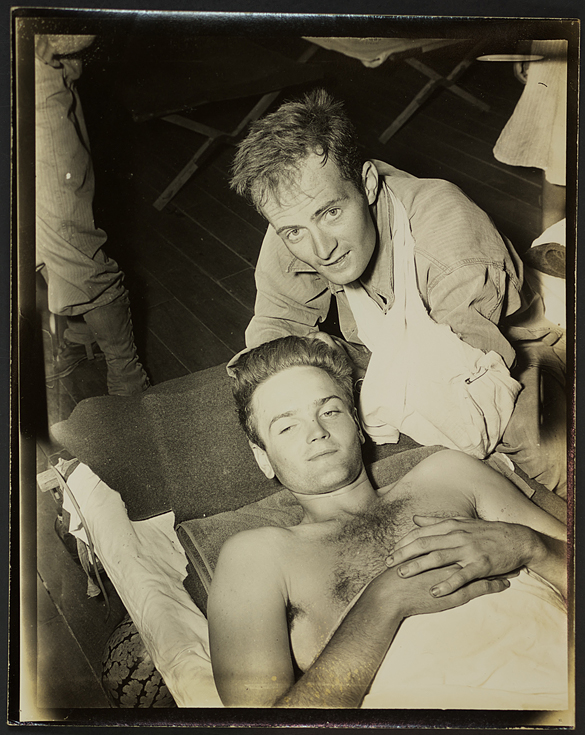

Marking its place, I pulled the “Leyte” envelope from the box, peered inside, and saw five negatives. I pulled one negative out of its protective Kraft paper enclosure. I couldn’t believe it—the very first item that I examined in the collection and I immediately recognized Hugh Morton’s face in the image: a copy negative of a photograph of Morton leaning over fellow signal corps photographer Conway Spanton!

Why was this so exciting? Because I was not looking at an envelope in the Hugh Morton collection. I was nearly 400 miles away from Chapel Hill.

Early Tuesday morning of Thanksgiving week, I set off for Carlisle, Pennsylvania (about 190 miles east of my final destination of Pittsburgh), taking a busman’s holiday to conduct some research at the United States Army Military History Institute, which is part of the United States Army Heritage and Education Center. Exploring its website and catalog the previous week, I discovered that the institute held several items on Camp Davis—where Morton was stationed before heading to the Pacific theater—and 1,982 photographs made by another 161st Signal Photographic Company photographer, Thomas L. Wood, who also served in the Pacific. Given the dozens of photographers who traversed the Pacific islands, I considered the Wood photographs to be a long-shot, and held more hope of finding useful material on Camp Davis.

When I arrived Tuesday afternoon, I first looked at the Camp Davis items, which turned out to be either too generic or too specific for my purposes. Next on my research cart was a document case containing envelopes and boxes of prints and negatives from the Thomas L. Wood photograph collection. The Wood collection comprised two photograph albums and a box; because of their large size and storage location, however, the albums could not be brought out to the research room without approval. While awaiting permission to use the albums, an institute staff member had pulled the box—the document case that held the negative envelope labeled “Original Leyte.”

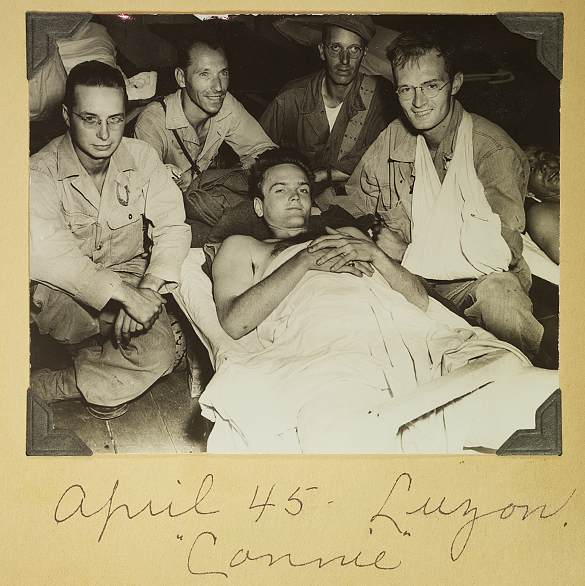

“But wait,” you may be saying: a copy negative isn’t an original negative. What was the original? After the excitement of my initial discovery subsided, I removed the remaining four negatives. One was a second copy negative of the Morton/Spanton portrait; the scene depicted in the remaining negatives (one original, two copies) I also immediately recognized from the Morton collection: a group of men, including Morton, seated around Spanton as he lies on a cot or a stretcher.

From the research room, I was able to check Wood’s negative against the group portrait in the online Morton collection. Unlike the Spanton/Morton portrait, the group portrait was not the same image as the one in the Morton collection (below).

I wasn’t able to get too far into the collection before the research room closed, so I stayed overnight and returned Wednesday morning. I methodically launched into the box of photographic material—starting on the opposite end from the Leyte negative with the photographic prints stored in Wood’s numbered and labeled original envelopes. After reviewing all the material in the document case, I did get to see the photograph albums. Lo and behold, in the second album . . .

. . . a print of the group shot with an identifying caption. Well, now there’s a problem . . . “Luzon” (in the caption) and “Leyte” (on the negative envelope) are two separate islands! Two mysteries solved (Wood being the likely photographer and when he made the photographs), but a new mystery added (location). Luzon makes more sense to me at this point, but more research will be needed to confirm that.

Some other place names on the envelopes and captions in the albums overlapped with places where Morton had ventured, but many more did not. I was able to identify a previously unidentified Morton landscape photograph made in the Pacific from a different image in the Wood collection: Mount Bagana on Bougainville Island on what is now part of Papua New Guinea. Using Google Earth, I was able to come pretty close to the spot where Morton likely made the photograph, and I recorded the latitude and longitude in the descriptive metadata. Morton was not portrayed in any of Wood’s Bougainville photographs that were dated from December 12, 1943 going forward, including a New Year’s Eve party at the close of 1943.

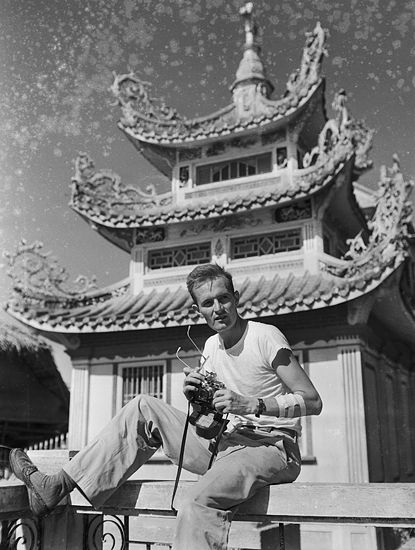

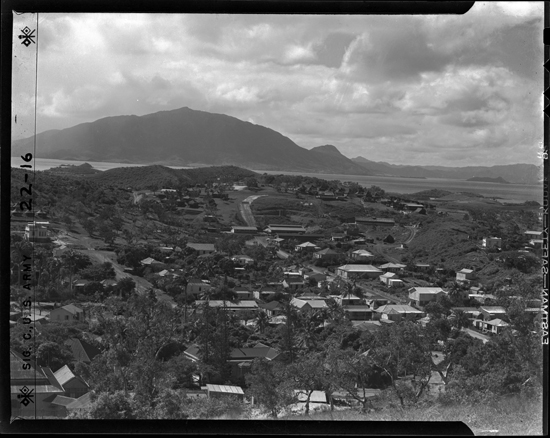

The location common to both Wood and Morton that proved to be the most rewarding was Noumea, New Caledonia. One print of Noumea with Mount Dore in the background labeled “Our camp upon hill” was taken from practically the same vantage point as a Morton negative featured in a previous blog post. Wood’s photograph identifies the central portion of the photograph as the headquarters of the 161st Signal Photographic Company.

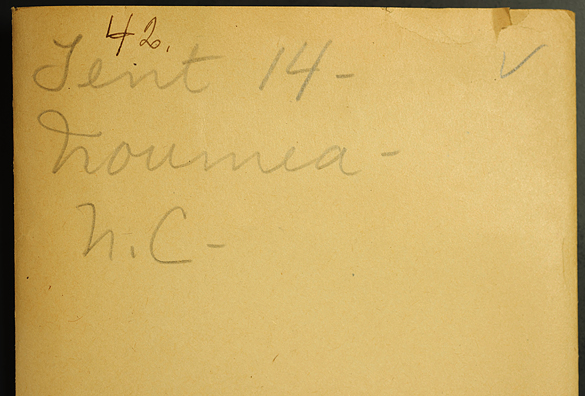

A print of the Spanton/Morton portrait was in Wood’s envelope #42 (both shown above). Envelope #43 — “Tent 14 – Miss/N.C.” — contained a group portrait of Wood, Spanton, and two others. From the images in these envelopes, it seems that Wood and “Connie” were good friends and tent mates.

Another photograph in the envelope, labeled “New Caledonia/June 44” on the verso, shows Thomas Wood (easily recognizable by that point in my research) and two other men. I knew a completely unidentified print of that photograph was in Morton collection (below).

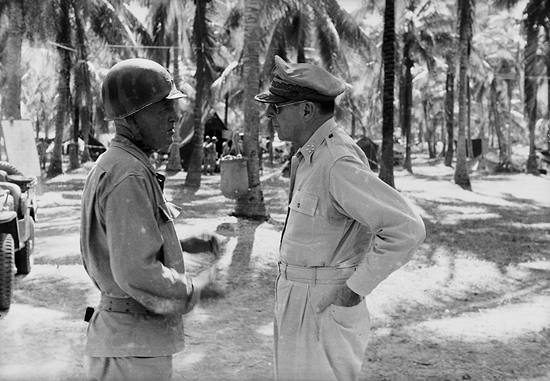

In the second photograph album, however, there was an even more interesting group portrait . . .

This group portrait, presumably members of the 161st Signal Photographic Company, places Morton and Wood in Noumea at the same time. There appear to be differences in the foreground landscaping, so the date may not be the same as the portrait of Wood posing with two others.

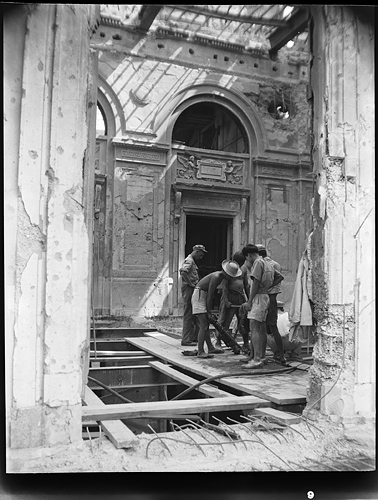

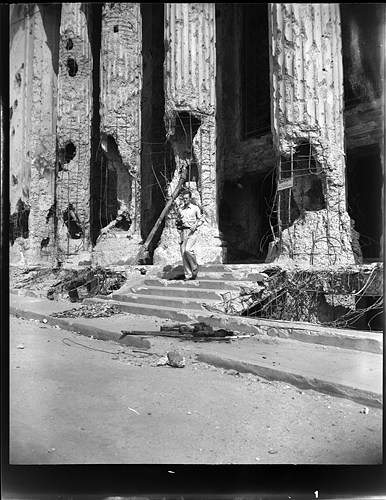

After finishing with the Wood collection, I had very little time left to look at photographs in the institute’s Signal Corps Photograph Collection. The views of Camp Davis predated Morton’s assignment there, so I moved on to a group of images arranged by location. I had asked the staff to pull images from a handful of locations, but the clock was poised at less than five minutes until closing time on the day before a holiday. I chose the folder labeled “Balete Pass.”

Inside was the biggest find of the trip.

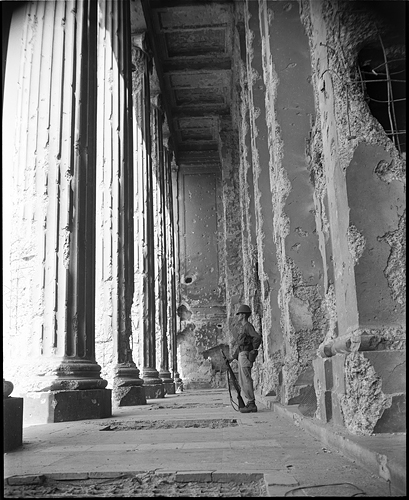

In the Hugh Morton collection, there is a photograph with the following caption:

A US Army Signal Corps Photographer is shown photographing infantrymen of the 25th Infantry Division as they are in process of knocking out a Jap pillbox position near Balete Pass, Luzon. The enemy is fiercely defending Balete pass because it is a key route to Baguio. The Japs set off an explosion which wounded both Infantry men and Cameraman shortly after this picture was taken. Photographer: Allen”

That caption does not name the photographer in the scene; the descriptive metadata we had for this image online did not include that caption. Both of these shortfalls have now been corrected. Who is the photographer in the scene? The faded but legible caption on the back of the print at the United States Army Military History Institute states: “Hugh Morton.”

A previous View to Hugh post, Saved by his camera, tells a bit more about that day.

A special note: Leyte is where General Douglas MacArthur famously proclaimed, “I have returned.” Many thanks to the staff at the Army Military History Institute for their assistance during my visit. I shall return.

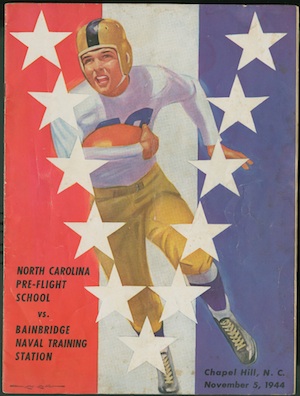

On November 5, 1944 The Cloudbusters hosted The Commodores from Bainbridge (Maryland) Naval Training Station. Coaching on the sideline that day for the Cloudbusters was a young Lieutenant named Paul W. Bryant. He would lead the University of Alabama to six national titles during the 1960s and 1970s, and would be known as “Bear” Bryant. Leading the Cloudbusters at quarterback was

On November 5, 1944 The Cloudbusters hosted The Commodores from Bainbridge (Maryland) Naval Training Station. Coaching on the sideline that day for the Cloudbusters was a young Lieutenant named Paul W. Bryant. He would lead the University of Alabama to six national titles during the 1960s and 1970s, and would be known as “Bear” Bryant. Leading the Cloudbusters at quarterback was