. . . Mr. Byram and his handful of youths went along this ridge and when they came to a dead bush they cut it. Lacking a vehicle that would negotiate the sand, they dragged it to the Lighthouse and before nightfall they had built a hedgerow thirty inches high for a distance of sixty feet, set well back out of reach of the tide. . . Daylight next morning found Mr. Byram and his boys out to see what had happened in the night. Nothing except the tops of their hedgerow of dead brush was visible.—from Ben Dixon MacNeill’s The Hatterasman.

Edward Jefferson Byram was the leader of the advanced detachment of the Civilian Conservation Corps contingent assigned to the land and lighthouse on Cape Hatteras in August 1935. Deeded to the state of North Carolina for a state park, the state transferred the land to the National Park Service in December 1936.

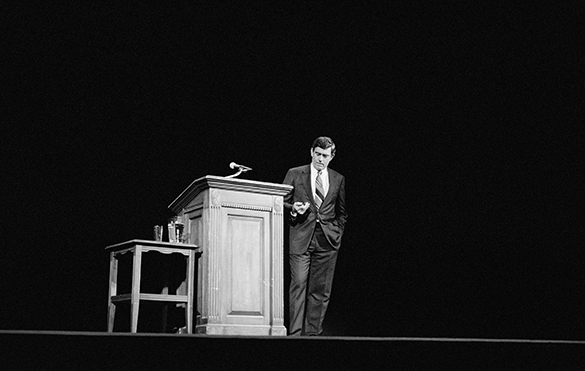

Today, September 8, 2021 marks the fortieth anniversary of another attempt to thwart the ravages of wind and sea against the lighthouse: the Save the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse fundraising campaign kickoff at the Mission Valley Inn at Raleigh. In 2009, Jack Hilliard wrote an extensive blog post about Hugh Morton’s role in saving the lighthouse. Jack’s story includes that event, but what happened the prior year that led to Morton’s involvement?

From time-to-time, Morton’s executive planners provide answers or clues. There are only a few entries on the topic in his 1981 planner:

- April 30—“TV 7-8AM WCTI-TV New Bern at Mission Valley re Lighthouse Jerry Dean”

- August 6—“Fly Hatteras Robert Baker”

- September 8—“noon—Gov. Hunt—Sen Helms Raleigh”

- October 8— 8:00 a.m. “Lighthouse meeting” with an additional entry: “Gov. Hunt – Nags Head – Hatteras”

Morton’s photograph held by Governor Hunt is from a 120 format negative (roll 1-101-3-3, frame 5). Several prints from that roll of film are in the Morton collection with a typed caption:

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in August 1981, with ocean shown less than 100 feet from its base. These photographs are a featured part of information being provided to the 100 County Chairmen in the lighthouse drive for funds in regional meetings in Asheville, Salisbury, Clinton and Rocky Mount Wednesday and Thursday April 7 and 8.

Hugh Morton’s name first appears in the press in association with saving the lighthouse on 26 July 1981. The previous day, during a news conference in Wilmington Secretary of the Interior Department James Watt and United States Senator Jesse Helms announced that Morton would head a general subscription to raise funds, harkening Morton’s campaign to bring the U.S.S. North Carolina to Wilmington in the early 1960s. Morton’s planner, however, has him in Linville and Grandfather Mountain. As listed above, his planner does suggest earlier involvement in April. (There is no planner extant for 1980.)

As for the lighthouse itself, public awareness of the lighthouse’s imminent danger surfaced in an Associated Press Reports article published by The Charlotte Observer on October 14, 1980. The report noted that local residents feared the lighthouse “might not make it through the winter” because tides were “gnawing away at its foundation” and its steward, the National Park Service, did not have a plan to save it. Ray Couch, president of the Outer Banks Preservation Society, said that its members were writing letters to their congressional representatives to draw their attention to “the seriousness of the situation.” William Harris, superintendent of Hatteras National Seashore, stated that only sixty to ninety feet of sand remained between the ocean and the lighthouse and acknowledged that the beach erosion at the site was “very acute.” He also stated that an architect and engineering firm was assessing the situation. He closed by saying, “The cheapest option is to move the lighthouse,” but “we have no money.”

Ten days later, a fierce storm struck the North Carolina coast and work crews “began a desperate battle against the sea,” wrote Charlotte Observer writer and photographer Jim Dumbell. Workers continued their prevention effort into Saturday as the storm produced twelve-foot waves that pounded the shore. The Associated Press picked up the story on October 27, which reads like a shorter version of Dumbell’s feature. The following day, news reports announced that the National Park Service agreed to construct a jetty as a $60,000 stopgap measure. An Associated Press article described the jetty as an “underground metal wall.”

An article the following year by National Geographic writer John L. Eliot revealed that the then recent round of erosion actually arose in early March 1980 after a strong nor’easter socked the eastern United States as far south as Florida, where the temperature plummeted to thirty degrees Fahrenheit in West Palm Beach. The North Carolina coast was hit with thirty inches of snow and sixty mile-per-hour winds. More importantly at the lighthouse, ten-foot waves battered the shore when high tides were the highest since the Ash Wednesday storm of 1962. After the October storm described above, another struck in December requiring more emergency buttressing along the shore near the foundation.

Addenda (September 9, 2021): Governor Hunt gave a prepared speech on 10 November 1981 during the three-day meeting of the travel council, making that date a candidate for the date Morton made the above portrait. The meeting took place at the Holiday Inn–Woodlawn in Charlotte. Also, The State published one of Morton’s color transparencies made during the same flight on the cover of its January 1982 issue.