If we do not start treating our environment with more respect—giving it time to replenish itself—we are in for trouble in the future. —John H. Glenn Jr., October 12, 1971 at Douglas Municipal Airport, Charlotte, North Carolina

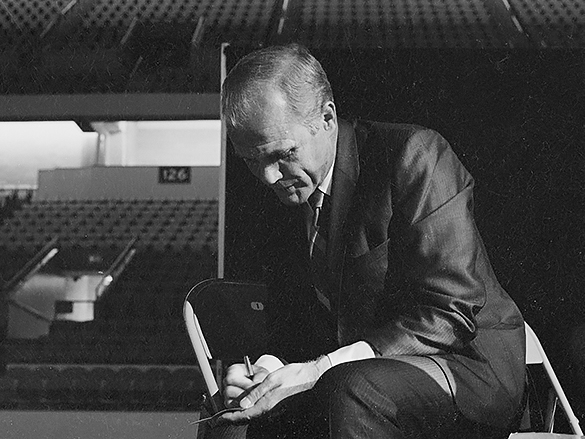

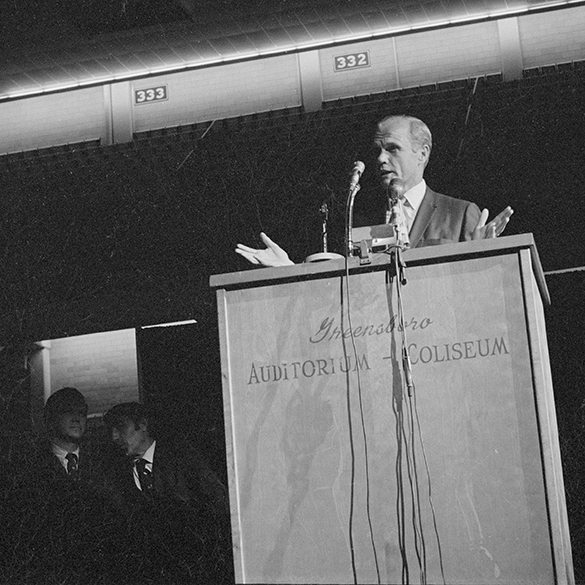

With John Glenn’s passing on December 8, I recalled the group portrait made by Hugh Morton at a campaign debt retirement party for Terry Sanford attended by Glenn and others. To see what, if any, other photographs Morton may have made of Glenn, I turned to the collection finding aid and found the following listing for fourteen 35mm black-and-white negatives: “Environmental Concerns #44: ‘Environmental Conference, Greensboro Coliseum: John Glenn, Stewart Udall, etc.,’ 1970s-1980s?”

Ah that tantalizing question mark . . . another Morton Mystery!

For those who don’t know, many newspapers on microfilm held by the North Carolina Collection have been digitized by newspapers.com. They can be viewed for free if you are on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus, otherwise you need to have a paid subscription. Searching the website quickly revealed that the conference occurred on October 12, 1971. On that day, the North Carolina Jaycees and possibly the North Carolina Conservation Council (only one source mentioned that organization) sponsored rallies in four airports across the state, capped off with an environmental conference that evening at eight o’clock in the Greensboro Coliseum. More time consuming, however, was piecing together various (sometimes conflicting) news reports to form a coherent picture of the day’s events. I don’t believe what follows, however, is the whole story so I encourage you to leave comments to help complete it. I sense that this post could lead to more on the topic of the environmental movement in North Carolina . . . and maybe even turn up more Morton Mysteries.

*****

Here are four points that provide some context for the story:

Conservationism into Environmentalism

The environmental conference and rallies occurred during the formative years of environmentalism in North Carolina, an era that began in 1967 according to Milton S. Heath Jr. and Alex L. Hess III in their essay “The Evolution of Modern North Carolina Environmental and Conservation Policy Legislation.” Preceding the “Environmental Era” was the “Conservation Era” that began at the turn of the twentieth century. Heath and Hess characterized the difference between these two periods in terms of state laws:

In North Carolina, the statutes that implemented . . . resource management programs at the state level contained policy statements that encouraged management and use of resources in contrast with the preambles of environmental-era statutes that stressed protection and preservation.

Hugh Morton’s life straddles that transition. His career includes a decade of service as a member of the North Carolina Board of Conservation and Development under governors W. Kerr Scott, William B. Umstead, and Luther H. Hodges from 1951 to 1961. It is during those years, too, that Morton begins to conserve and develop Grandfather Mountain.

Earth Day

The very first Earth Day was April 22, 1970. Before the end of the year, on December 2, the United States Government established the Environmental Protection Agency. The new agency was a consolidation of several entities within the federal government. This accomplishment stemmed from the recommendation of President Richard M. Nixon as part of his “Reorganization Plan No. 3 of 1970,” which he proposed to the Senate and the House of Representatives on July 9th. In that document Nixon noted, “Our national government today is not structured to make a coordinated attack on the pollutants which debase the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the land that grows our food. Indeed, the present governmental structure for dealing with environmental pollution often defies effective and concerted action.”

North Carolina Legislation

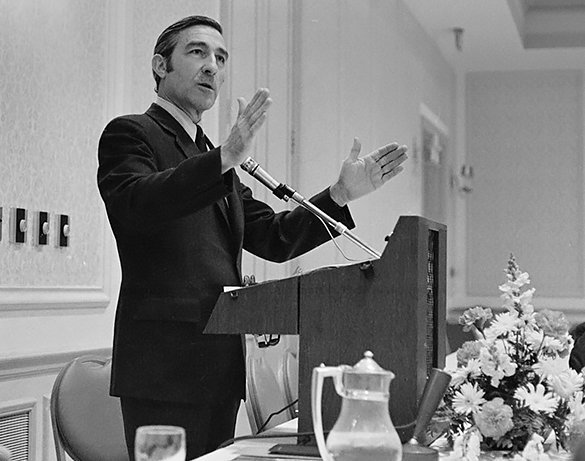

Nearly one year after the first Earth Day, on April 8, 1971, North Carolina Governor Robert Scott sent the General Assembly an environmental message accompanied by several related bills. The year saw the enactment of the North Carolina Environmental Policy Act of 1971, also known by the acronym “SEPA” (State Environmental Policy Act), and the state’s Environmental Bill of Rights, introduced by State Senator Hargrove “Skipper” Bowles. The latter was enacted on June 21, 1971. According to Heath and Hess, “the bill as introduced was drafted at Senator Bowles’ request by University of North Carolina Law School Professor Thomas Schoenbaum. The voters of the state approved the proposed constitutional amendment in the general election on November 7, 1972.”

Politics

The October 12, 1971 “Environmental Emphasis Day” (a phrase used by two of the newspapers consulted for this post, but only the Charlotte Observer used capital letters) took place during the very early phase of the campaign season for the upcoming 1972 North Carolina primary elections on May 6. Hugh Morton announced his gubernatorial candidacy for the Democratic Party on December 1, 1971.

*****

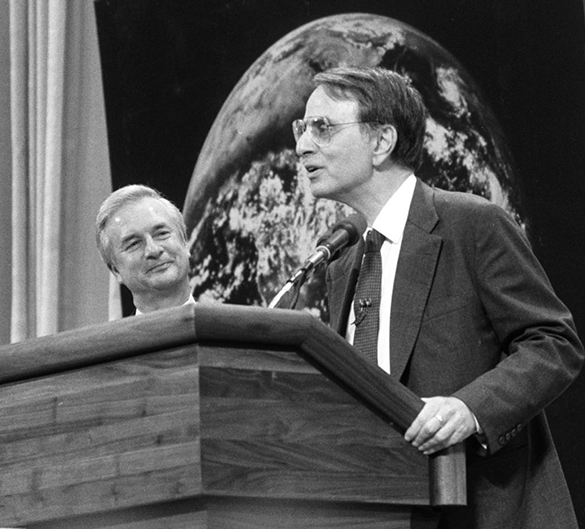

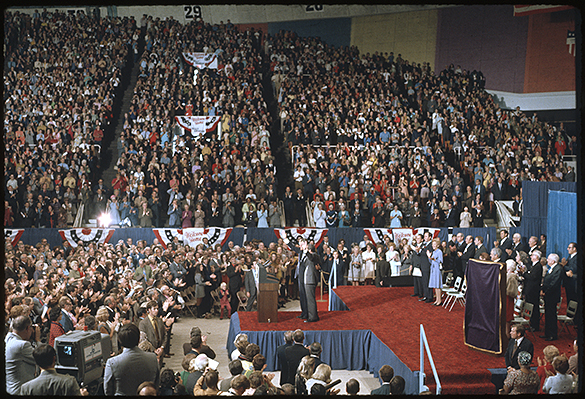

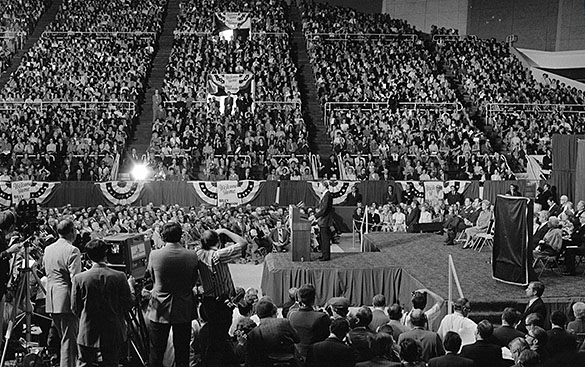

On September 23, 1971 North Carolina Jaycees president T. Avery Nye Jr. announced that Colonel John H. Glenn Jr. would be a keynote speaker at an environmental rally at 8:00 p.m. at the Greensboro Coliseum, Nye noted that other speakers would include Oregon’s Republican United States Senator Robert Packwood and former United States Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. The Jaycees described the upcoming event at the coliseum as the “first of its kind in the nation.” The Greensboro Daily News reported that the day would start with Glenn and Udall, “accompanied by announced candidates for governor of North Carolina,” making a “whistle-stop tour” of the state “traveling by private, executive-type aircraft” to rallies at airports in Asheville, Wilmington, Charlotte, and Raleigh-Durham. Packwood would unite with Udall and Glenn in Greensboro after the tour for the evening rally. North Carolina’s United States Senator B. Everett Jordon “and most other members of the state’s delegation to Congress and members of the state’s General Assembly” were expected to attend. Nye also encouraged the general public to attend, noting that no admission or parking fees would be charged. The rally, Nye said, “is being staged to give North Carolinians an opportunity to show their support for good environmental legislation.” Attendees were going to be asked to complete a questionnaire on state environmental problems, with the results to be distributed to legislators and members of Congress.

The choice of John Glenn, the celebrated astronaut who nearly a decade earlier had become the first American to orbit Earth, to be a keynote speaker for an environmental conference may seem puzzling to us today, but it was not so at the time. Glenn had recently chaired Ohio’s Citizens Task Force on Environmental Protection, a bipartisan task force announced by that state’s Governor-elect John J. Gilligan on November 25, 1970. The panel issued it’s final report in June 1971. After its publication, Glenn toured around the country promoting Ohio’s study as a model for other states.

Three subsequent articles provided more details about the upcoming event: one in the Asheville Citizen on Monday, October 4, the second in a Daily Tar Heel article published on October 8, and the third in the Asheville Citizen-Times on Sunday, October 10. The Asheville Citizen article’s headline read “Environment To Be Frequent Topic During October In North Carolina.” The article described several activities scheduled for the month, including the “statewide environmental rally” in Greensboro that would be preceded on the same day by four airport rallies in Raleigh-Durham, Wilmington, Charlotte, and Asheville. (This order would be the actual order of the tour.) In addition to listing the expected speakers and invited individuals for the evening rally, the article stated that a “30-minute brand new movie on North Carolina and its environment” would be shown that night.

According to the Daily Tar Heel article, the Jaycees’ event was now co-sponsored with the North Carolina Conservation Council—no other resource, however, mentions this. The day was to begin in Washington D.C., where Governor Bob Scott, Bowles, Udall, and Glenn would fly to Raleigh-Durham Airport for the first of the four airport rallies. Later in the day in Greensboro, all but one of the state’s congressmen would fly to Greensboro from Washington for the evening’s rally. According to the October 12 issue of the News and Observer, however, Governor Scott met the Glenn-Udall party at Raleigh-Durham Airport and then traveled with them to the subsequent rallies. Scott did not attend the Greensboro event; instead, he returned to Raleigh to celebrate his wife’s birthday.

The Citizen-Times article published just two days before the eventful day stated that the North Carolina Jaycees “put about a year of planning and hard work” into the event. Thad Woodard, the Jaycees’ state environmental chairman, said,

The rally provides an opportunity for people of the state who have been expressing interest in environmental problems to show the strength of conservationists and environmentalists in North Carolina. We believe these problems have to be approached both on a legislative and on an educational basis . . . and our legislators and educators need to know that people are genuinely interested in the environment.

The Citizen-TImes also informed readers that the airport visits were to be made in two six-passenger planes provided by First Union National Bank and Northwestern Bank.

*****

News coverage from the host cities’ newspapers shed light on some of the activities for the rallies held on October 12. The News and Observer assistant city editor Daniel C. Hoover covered the day’s events, but he did not describe much about the Raleigh-Durham airport rally. Hoover only wrote that Governor Scott “called on official in coastal counties to declare a moratorium on all permits to destroy dunes for development pending a study authorized by the general Assembly.” Hoover then quoted Scott, who said he would “propose, in the near future, to call together all county and municipal officials of our coastal counties, along with appropriate state officials, to explore solutions to existing and potential coastal problems.”

At the next stop, Ronald G. Dunn, staff writer for the Wilmington Morning Star estimated their airport crowd to be seventy-five people. John Glenn drew upon his experiences as an astronaut. He told those gathered that Earth is “in effect a spaceship on which the warning lights are on, so therefore, as spacemen we should take action immediately to save our environment.” He described the obviousness from space that Earth’s atmosphere is a very shallow layer and that America was likely among the world’s worst polluters. He also urged involvement, saying “People interest in the United States gets action, so get interested.” An accompanying UPI photograph with caption depicted Scott, Glenn, Udall and “gubernatorial aspirant Hargrove Bowles” at Raleigh-Durham rather than a scene from the Wilmington airport rally. Bowles was able to join the group because, as of the environmental emphasis day, he was the only officially declared candidate for governor.

Only thirty people attended the rally in Charlotte according to Charlotte Observer staff writer Susan Jetton. Perhaps as a result of the sparse attendance, Governor Scott said “efforts of decision-makers are not very successful without the active support of the people.” Glenn again drew attention to the “warning signals” of pollution that were appearing “on this space ship earth.” He added, “If we do not start treating our environment with more respect—giving it time to replenish itself—we are in for trouble in the future.”

The Asheville visit drew more than one hundred people, according to staff write Connie Blackwell. Glenn used the “warning lights” metaphor here, too, but Blackwell added that Glenn did not see himself as “one of the doom and gloom boys.” Bowles urged the approval of the Environmental Bill of Rights. Udall and Scott each addressed proposed aspects of the Tennessee Valley Authority project in western North Carolina, the Mills River Dam and Reservoir. Udall, noting his many visits to western North Carolina during the previous ten years, said he was there that day because “I don’t want to see North Carolina go down the same road” as California. He noted that his “attitudes have made about a 180-degree turn in the past ten years. It used to be if a dam was mentioned, I automatically thought it was a good idea. Now, my reaction would be that it should not be built.” He continued,

Industrialists came into these valleys years ago and said. “We’ll give you jobs, but we’ll ruin your mountain streams and stink up your pure air.” They accepted because jobs were so badly needed. Now we are beginning to realize that it didn’t have to be that way.

*****

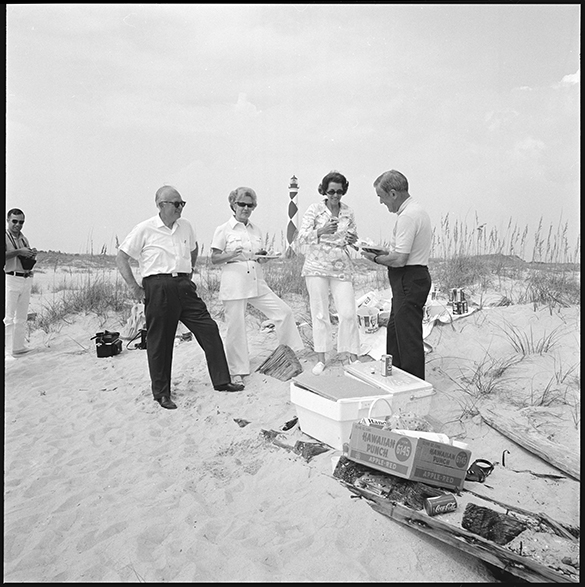

Several newspapers and the Associated Press (AP) reported on the evening conference. David S. Greene of the Greensboro Daily News, report that the first speaker was Udall, who wrote that Udall described “North Carolina as a leading state in maintaining ‘the standard of living,'” but also one that needed to prevent further “despoilment of the environment.” Udall encouraged attendees to “Hold on to what you’ve got.” Udall referred specifically Bald Head Island, which he had seen during a flyover earlier in the day. The AP reported that private developers wanted to build a “plush resort” there and that environmentalists had asked the state to purchase it and maintain its natural state. Greene noted that the audience applauded when Udall “urged American to listen to young environmentalists.” Quoting Udall: “If they have something to contribute let them contribute. It’s their world.”

The News and Observer reported that Udall, as “the keynote speaker,” suggested that Bald Head Island be added to the existing Cape Lookout National Seashore. He added during a press conference following the rally that there was “a hang-up” on how to pay for the acquisition. Hoover wrote that Udall continued by offering a few options “as prospective gubernatorial candidate Hugh Morton hovered at his shoulder snapping pictures.”

Senator B. Everett Jordan then introduced John Glenn, first noting legislation to reduce automobile exhaust and the problem of “one hundred million automobile tires lying around our countryside” plus twenty-eight billion bottles, a like number of cans, and millions of tons of paper products. Jordan then encouraged the audience to increase the recycling of products that have been seen as waste.

Recalling his orbital spaceflight John Glenn observed, “We do have closed loop systems that have to refurbish themselves, but we are, in fact, in danger of overtaxing our systems.” He said nature was waving “red flags” of warning and that “people power” was causing industry and government to take notice. That, in turn, he said “can generate the heat to get something done. People power, you bet.” He then dismissed the saying “the solution to pollution is dilution.” Glenn said, “We see the red flags going up . . . we better do something about it.”

Roy Sowers, director of the North Carolina Department of Natural Resources introduced Republican Senator Robert Packwood of Oregon, the concluding speaker. Packwood drew much attention and applause as he addressed measures that could advance population control. “I am committed,” he said, “to stopping this population binge, and reducing it, turning it around.”

*****

Despite the presence of so many politicians, the North Carolina Jaycees tried its best to keep the event from being political, according to Nat Walker in his “Political Notebook” column for the The Greensboro Daily News with the headline “Environmental Rally Becomes Political Gathering—Naturally.” Walker said, “They succeeded—sort of.” Only three North Carolina politicians got to speak from the rostrum—Bowles, Sowers, and Jordon—leaving the remaining “real or potential” candidates to “rely on mingling with the crowd or finding some excuse to stand in front of the audience.”

Mid October was an interesting time in Hugh Morton’s life. A month earlier, Morton attended the Governor’s Down-East Jamboree as a undeclared candidate for the 1972 Democratic Party primary. He would officially declare his candidacy on December 1. This meant that on October 12 Morton was still an “unofficial” candidate, and was not invited to participate in the flights to the airport rallies. Two newspapers reported specifically about Morton on that day. The Charlotte Observer characterized Morton as “unhappy.” In Charlotte, Morton said that he had, “done more in an environmental way than anyone now running for governor.” He acknowledged that being an unannounced candidate prevented him from participating. The Greensboro Daily News painted Morton as being in a different mood at the evening’s conference. Bowles, as an “announced” candidate for governor, got to introduce Udall because C. C. Cameron, a member of the state Board of Natural and Economic Resources, did not attend. Walker wrote that Morton “appeared miffed” and “pointedly noted that the Jaycees had extended him an invitation to attend the coliseum function.” Walker then recounted a scene where a “woman reporter” asked Morton when he would announce for governor. Morton snapped, “When I get ready.” Walker concluded that the reporter “Apparently couldn’t think of a follow up question and left red-faced.”

Seven weeks after President Harry S. Truman visited Winston-Salem for the

Seven weeks after President Harry S. Truman visited Winston-Salem for the

In a few of the frames there is a person on the beach who wears a boater-style “Morton For Governor” straw hat (third from the left in the above photograph). Another Hugh Morton mystery solved . . . one I didn’t know we had before working on this blog post.

In a few of the frames there is a person on the beach who wears a boater-style “Morton For Governor” straw hat (third from the left in the above photograph). Another Hugh Morton mystery solved . . . one I didn’t know we had before working on this blog post.