This year, 2019, marks several special anniversaries for the United States space program. Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Apollo 11 launch that carried the first humans to the lunar surface on July 20, 1969. Morton Collection volunteer, Jack Hilliard, takes a look at these celebrations. Then, in an afterward, I’ll share my current thinking on Morton’s photographs made during the Apollo 11 launch.

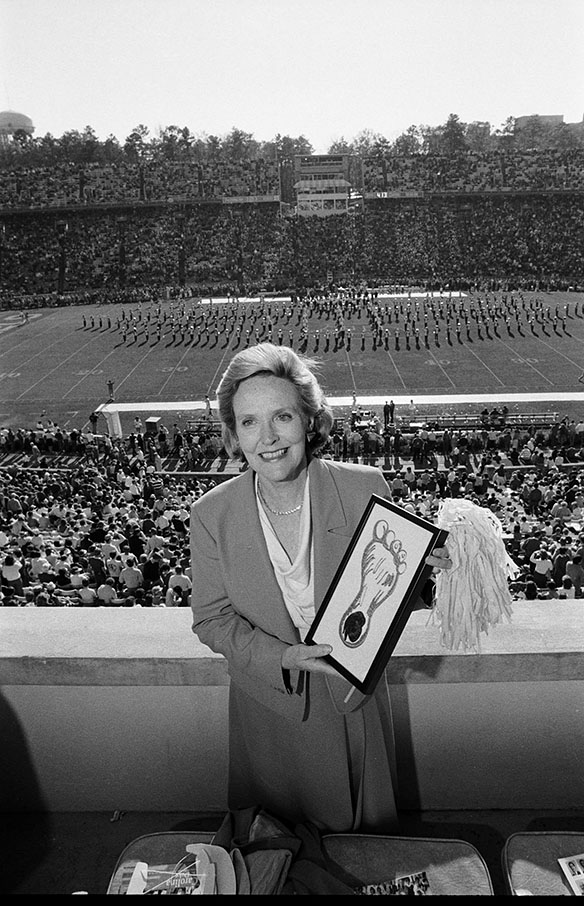

Soon after NASA announced its “Mercury 7” astronauts on April 9, 1959, the agency selected Morehead Planetarium on the UNC campus as “the place” for celestial navigational training. Between 1959 and 1975, nearly every astronaut who participated in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project programs trained at the planetarium. All seven of the Mercury team and eleven of the twelve astronauts who walked on the moon trained there. Longtime planetarium director Tony Jenzano liked to claim that “Carolina is the only University in the country, in fact the world that can claim most all the astronauts as alumni.” So, as we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the first moon launch and landing, we must give a tip of the hat to the folks at Morehead who played an important part in the most important peacetime undertaking of the 20th century.

Since I began working with Stephen Fletcher at Wilson Library in 2008, we have determined that Hugh Morton was a frequent visitor at the Kennedy Space Center for Apollo launches. We have determined that he was there for Apollo 9, Apollo 10, Apollo11, and Apollo 14. (He was likely at the launch of Apollo 8 and Apollo17, but we haven’t documented those images yet.) Over the years, we have written blog-posts about three of the Apollo fights: Apollo 9, Apollo 11, and Apollo 14.

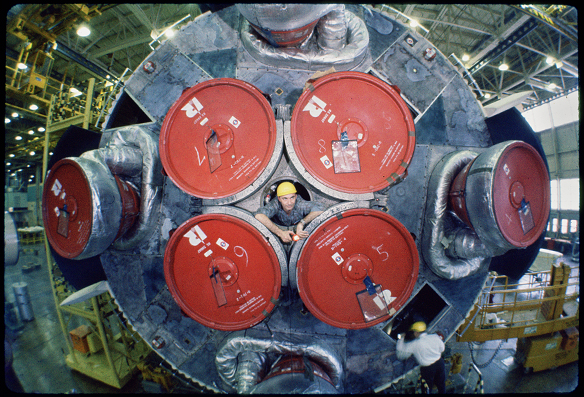

In February of 1965, Morton visited the NASA Michoud Assembly Facility, a part of Alabama’s Marshall Space Flight Center, but located in New Orleans. There he took several pictures of the Saturn 1B under construction. The Saturn1B would be used for the launch of Apollo 7, in 1968, three Skylab manned launches in the early 1970s and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

About two years after Hugh Morton photographed the Saturn 1B at Michoud Assembly Facility, he and wife Julia were part of a fifty-person tour of Florida by the Travel Council of North Carolina. Mrs. Dan K Moore, the state’s First Lady, headed the tour. On Monday, January 23, 1967 the group visited the Kennedy Space Center—just four days before the tragic launchpad fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew. Astronauts “Gus” Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee died while training for the first Apollo manned mission, which had been scheduled for February 21, 1967.

The Apollo program would not make a manned flight until the launch of Apollo 7 on October 11, 1968.

Fifty years ago today, on July 16, 1969, Hugh Morton was one of the more than 3,500 accredited news reporters and photographers representing fifty-six countries, at NASA’s press site, three and a half miles across the Banana River from the Pad A launch facility at Kennedy Space Center. There are Morton images from the press site complex as well as the VIP viewing site where Morton took a photograph of former President Lyndon Johnson.

More than one million spectators jammed the Florida beaches and highways. Among the dignitaries at the VIP viewing site were General William Westmoreland, Chief of Staff of the Army, four members of President Nixon’s cabinet, sixty ambassadors, nineteen state governors, forty mayors, and two hundred congressmen. Vice President Spiro Agnew accompanied former president Lyndon Johnson and wife Lady Bird.

An estimated twenty-five million TV viewers in the United States watched the proceedings and the live coverage was available in thirty-three countries. President Richard Nixon viewed the launch from his office in Washington with NASA liaison officer, Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman.

As the launch time approached for Apollo 11, a few fluffy clouds could be seen, with the temperature in the high 80s and a slight breeze. NASA’s weather team at Patrick Air Force Base just south of the space center reported “flawless” launch weather.

At 9:32 am (EDT), on July 16, 1969, the mighty Saturn V (AS-506) rocket began fulfilling President Kennedy’s 1961 goal of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth,” with the historic launch of Apollo 11.

Afterword by Stephen

It’s struck me as odd that there are only seven 35mm slides from the Apollo 11 launch in the Morton collection, none of which depict blast off. Thinking photographically about the moment, I’ve come to believe that there are 35mm color negatives. Here’s why . . .

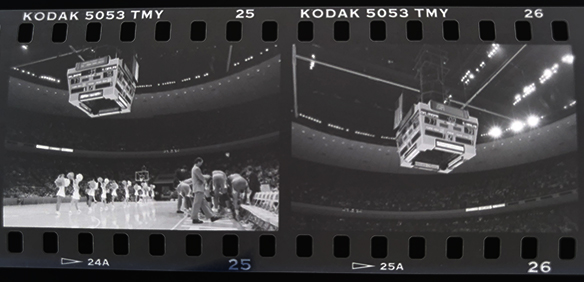

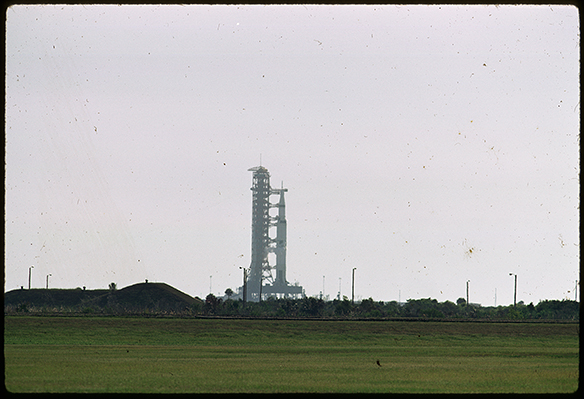

The 35mm slides that exist are from the end of a roll of film—slides 31 through 38, with slide 35 missing. Digital scans made from four of those slides can be seen online via the link in the story above. Sequentially:

- frames 31 and 32 show photographers lined up at the press site next to the Vehicle Assemble Building at the Kennedy Space Center;

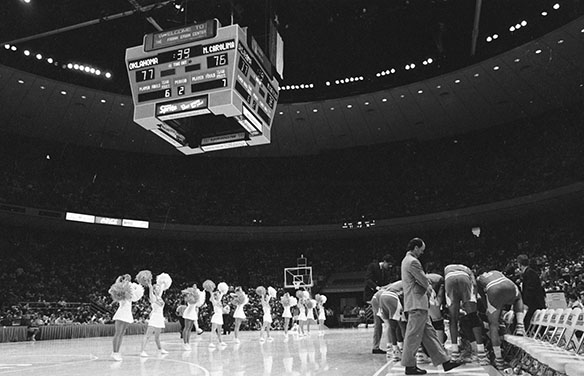

- slides 33 and 34 show the Saturn V rocket on the launchpad in the distance;

- with frame 35 missing, slides 36 and 37 depict a sparsely populated grandstand; and

- slide 38, the final frame, is the portrait of LBJ wearing sunglasses and looking like he may have been in the sun a bit too long (see the scans above),

At this point, Morton needs to reload his camera with a fresh roll of film. It’s either a between slides 34 or 35 and slide 36, or after frame 38 that I think misfortune struck.

I believe Morton may have had three cameras in operation—two positioned on tripods, and one carried with him. Why? There are two unidentified rolls of 35mm color negative film (i.e., not color slide film) in the collection depicting a rocket launch—one roll is oriented horizontally the other oriented vertically. Both are severely out-of-focus. From the street lamp positioned in the foreground, they appear to be from the same location as the slide above.

From a content perspective regarding the slides, why would LBJ be in the press section? More likely he would have been in the dignitaries section, which if that is what the grandstands above depict, then we can see was fairly empty. Is this because it was early before liftoff at 9:32, or after when people would have begun to leave? I think the later because the shadows are not long. Morton would have photographed around the press site, then switched his attention to liftoff, then wandered back to the dignitaries section.

Somehow or other, I think the cameras with telephoto lenses on tripods lost their focus. Or maybe there is another scenario. What do you think?