This post was written by John Blythe, a Digital Curation Fellow in UNC’s School of Library and Information Science and a member of the Digital Libraries class just wrapping up their Morton project. Here’s a brief bio of John provided by SILS:

John Blythe, a native of Chapel Hill and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill alumnus, came to the School of Information and Library Science (SILS) following an 18-year career in journalism that included stints as a Web editor, radio producer and newspaper reporter. His interest in digital curation and preservation grew out of an encounter with a box of old tapes made by his grandfather [LeGette Blythe] during a long career as a newspaperman and writer in North Carolina.

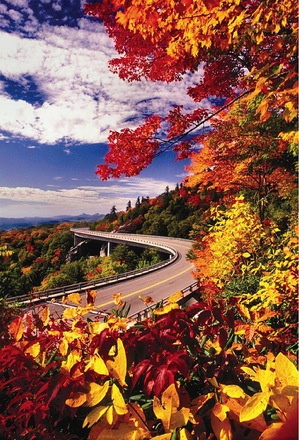

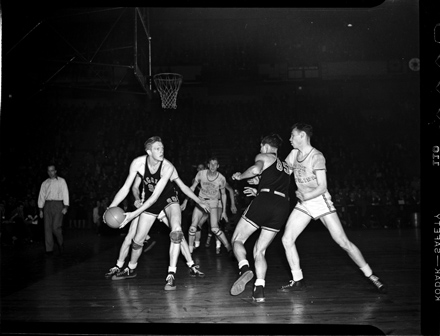

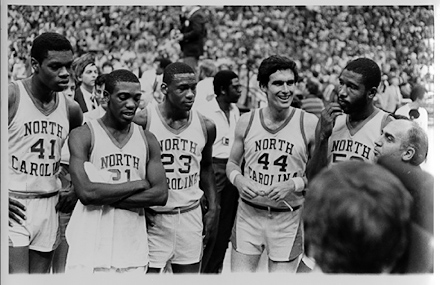

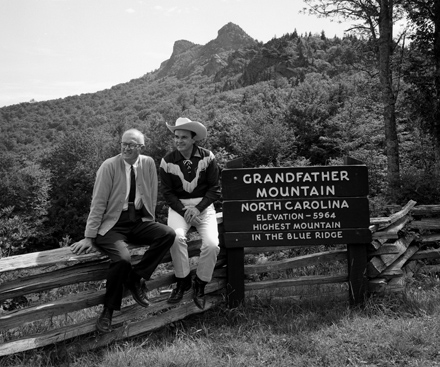

As a native Chapel Hillian, a UNC alum and a Tar Heel basketball fan, I was used to seeing Hugh Morton sitting cross-legged on the sidelines at the Smith Center (and at its predecessor Carmichael Auditorium) snapping photos of men’s basketball games. I also knew that Morton and his family owned Grandfather Mountain. On several occasions as a teenager, I joined the freckled and pale-skinned masses who mount an annual July pilgrimage to the mountain’s MacRae Meadows (which bears the name of Morton’s maternal ancestors) to celebrate all things Scottish at the Highland Games.

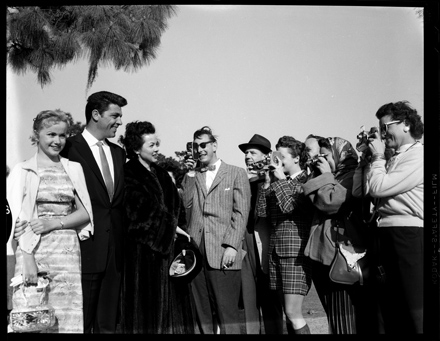

But it wasn’t until I joined with five of my library science school classmates in digitizing some of Morton’s photos that I realized how prolific a photographer he was. More than 500,000 images! I was also surprised to learn how long photography had been one of Morton’s passions. And what a chronicler of UNC he was. As we digitized we found negative after negative of UNC students, some candid and some posed. There was the series of photos taken either in McCorkle Place or Polk Place of a male student reclining in the grass joined by a changing group of women. Posed? Yes. They had the look of a clothing ad you’d find among the inserts in a Sunday newspaper. I thought, “Who is this guy? How did he manage to attract so many women? And why wasn’t I so lucky during my undergrad days?”

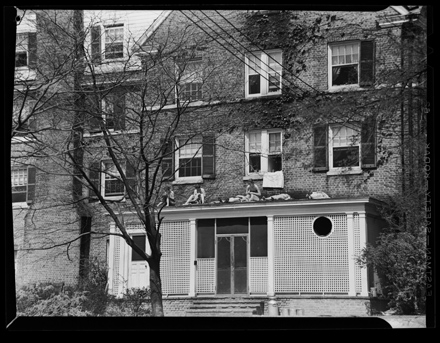

There was another negative. This one appeared to be candid. Taken of a dorm, it featured some young women lounging on the roof of an enclosed porch. The negative was overexposed and tested my newfound digitization skills. “Remember what Stephen said,” I told myself. “Increase the contrast here. Put a little more shadow there.” As I followed these steps, my mind wandered. I was taken back to the Chapel Hill of my youth. It was a hot summer day. We were driving home from swimming lessons at Bowman Gray Indoor Pool. And there, as I looked out the window, was the porch and the dorm. Was it Spencer dorm? Alderman? McIver? Kenan? The image wasn’t clear enough in my head. Briefly there was the nostalgia for the old, the dislike of change and the sentimentality for the Chapel Hill we used to call “The Village.” But the photo also summoned back happy memories. The relaxed feel of a six-year-old whose summer is filled with possibilities and few limitations. There’s the chance to play. And play again. There’s summer nights of “Kick the Can” and “No Bears Out Tonight.” And going barefoot all day.

As a budding archivist, I’m learning that documentation is important. We need to know what dorm is featured in the photo. We should provide the names of the happy couples reclining in the grass. Mr. Morton, it seems, liked to take photos more than he liked to record who was in them. As Stephen and Elizabeth have told us, they’re dependent on you (the reader) to help us with that documentation. That’s the professional speaking. But, speaking personally, as someone whose memories of Chapel Hill now span five decades, I’m just as happy to look at these photos and imagine. That’s the Hugh Morton I’ve now come to know—a man who’s provided the opportunity to get away from daily responsibilities and daydream.

—John Blythe

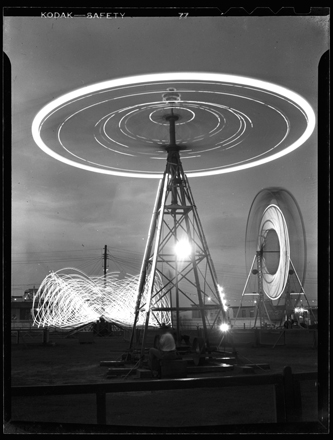

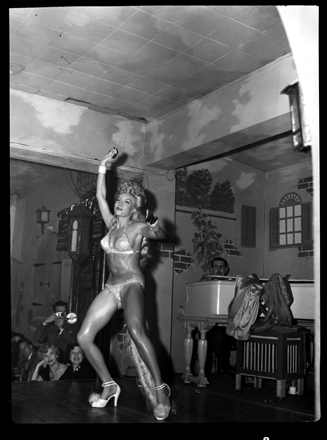

Wilmington’s 61st annual North Carolina

Wilmington’s 61st annual North Carolina