Hugh Morton’s energetic promotion of travel and tourism in the Southern Appalachians is well known. This High Country Press article provides Spencer Robbins’ first-hand perspective on Morton’s tourism work, which included helping found both the Southern Highlands Attractions Association and the High Country Host. (Please note: the Goodman article reflects personal perceptions of events, and contains at least one inaccuracy when it states that Morton considered a run for governor in the mid-1980s; it was in 1971 that Morton announced his candidacy for the 1972 election, but he dropped out before the primary.)

Morton’s boosterism is definitely reflected in the images he produced. In addition to the hundreds (thousands?) of shots in the collection taken of, on, or around Grandfather Mountain, there are numerous photos of other attractions including outdoor dramas, lighthouses and other coastal landmarks, the Barter Theatre in Virginia, Georgia’s Rock City, The Blowing Rock, Tweetsie Railroad, and the wonderful Land of Oz on Beech Mountain. (Some of these will be featured in a later blog posts, so stay tuned!)

But here’s one we just can’t figure out. This splotchy negative appears to show a re-creation of the giant’s house from the Jack and the Beanstalk story, shown with a real-life boy to provide perspective. The calendar on the wall reads, “Jack & Co. We Grow ‘Em Big! Dealer in Beanstalks at Magic Mt. Blvd. Pho.: Fe Fi Fo Fum.” The date on the calendar (oddly) is “Augustus 1063,” a month which apparently had 33 days. I know the J & B tale is old, but that old?

Part of my fascination with this image is that it seems vaguely familiar, as if I might have visited this place as a kid. Help me out—do you know why, where, when, or of whom this picture was taken?

Memorial for JFK, May 1964

Tomorrow, Thanksgiving Day, marks the forty-fourth anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Six months after his death, on Sunday, 17 May 1964, the state of North Carolina held a memorial service for Kennedy in Kenan Stadium on the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill campus.

In an effort to raise money for the Kennedy presidential library, “a living memorial,” each state pledged to raise funds. Governor Terry Sanford set the state’s goal at $230,000 (the eqivalent of $1.5 million in 2007 dollars), and Hugh Morton chaired North Carolina’s fund raising effort. An estimated 12,000 people attended the memorial, paying $10.00 (about $65.00 today) to attend and contribute toward the goal. As the date drew near, the governor announced that students were to be admitted free of charge because it was determined that sufficient contributions from the community had been raised. The News and Observer noted in its report the following day that no other state in the country had yet to raise money by public subscription, and that eighty percent of the state’s goal had been met.

The memorial featured a tribute by Billy Graham and addresses by Governor Terry Sanford; Luther H. Hodges, former North Carolina governor and then current United States Secretary of Commerce; and Senator Edward Kennedy, brother of John F. Kennedy. In the photograph above, Rose Kennedy, mother of the former president, is seated on the platform with Hugh Morton (left) and Terry Sanford (right). There are several slides of the event in the collection, but the photographer is unknown.

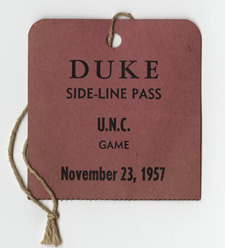

Battle for the Victory Bell

It’s that time of year, and in honor of this Saturday’s UNC-Duke football game, we thought we would revisit the same event 50 years ago: the dramatic November 23, 1957 face-off at Wallace Wade Stadium. UNC coach Jim Tatum had suspended quarterback Dave Reed a few weeks earlier in the season (prior to the Wake Forest game), and “Dook” was expected to win . . . making the Heels’ surprise 21 to 13 victory all the sweeter.

It’s that time of year, and in honor of this Saturday’s UNC-Duke football game, we thought we would revisit the same event 50 years ago: the dramatic November 23, 1957 face-off at Wallace Wade Stadium. UNC coach Jim Tatum had suspended quarterback Dave Reed a few weeks earlier in the season (prior to the Wake Forest game), and “Dook” was expected to win . . . making the Heels’ surprise 21 to 13 victory all the sweeter.

Hugh Morton was on the sidelines, of course, and we have his press pass (above) to prove it. After the game, Morton made a well-known photograph of Coach Tatum embracing an emotional Reed. That photograph is featured on page 168 of the 2003 book Hugh Morton’s North Carolina. The image below shows an enthusiastic but unidentified UNC fan in the stands that day, wearing buttons that read “Beat Dook” and “I Told You So.” Do you know who this is?

Amazing trick photography!

This is one of the more amusing shots I’ve come across so far in the Morton collection (I cropped the version at left for maximum effect). The picture was taken sometime during Hugh’s days at Camp Yonahnoka, where he took his first photography course in 1934 and served the following five summers as the camp’s photography instructor. It’s a good example of Morton’s appreciation for visual humor, something I’ve noticed throughout the collection.

This is one of the more amusing shots I’ve come across so far in the Morton collection (I cropped the version at left for maximum effect). The picture was taken sometime during Hugh’s days at Camp Yonahnoka, where he took his first photography course in 1934 and served the following five summers as the camp’s photography instructor. It’s a good example of Morton’s appreciation for visual humor, something I’ve noticed throughout the collection.

See below for the uncropped version, which shows how this mind-blowing “feat” of perspective was achieved. (Zing!) Just goes to show that some things—including puns—will never stop being funny.

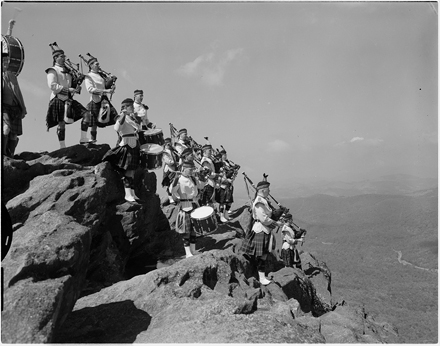

"It's a big noise."

“They weren’t designed to be played in recording studios. They were designed to be played on the tops of mountains,” the voice-over said on the radio as bagpipes in the background played “Amazing Grace.” I stopped making my morning tea when I heard that. A Hugh Morton photograph just flashed in my memory. “There’s no escaping that collection!,” I thought (in a good way).

I was listening to NPR early Sunday morning when that promotional spot for Weekend Edition Sunday aired, but Ollie, my dog, needed to be walked and I missed the story. Fortunately NPR posts its news programs on its Web site so if you missed it too, you can hear “Royal Scots Dragoon Records ‘Spirit of the Glen'” featuring the album’s producer Jon Cohen. Cohen talks about the challenges of working with the military band, and how orchestrating the sound of bagpipes compares to producing recordings for bands as diverse as the Backstreet Boys and the OperaBabes.

The Hugh Morton photograph that came to mind Sunday morning is actually a postcard in the Durwood Barbour Postcard Collection. It depicts a group of bagpipers and drummers on top of Grandfather Mountain during the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games. See the North Carolina Collection’s short history about the games in the “This Month In North Carolina History” entry written this past August. And now would be as good a time as any to mention the large ongoing project of digitized North Carolina postcards by the NCC staff.

You know, the strands of serendipity wend their ways on the strangest paths. I did a bit of fruitless searching for the original color slide, so I asked Elizabeth if one of those boxes you see on the table in her post, “A Processor’s Perspective,” had any Highland Games negatives. She pointed to the box and I grabbed the first envelope I saw with black-and-white negatives (easier to scan!) labeled “’61 Games—GMTN.” Inside were several 120 format (2-1/4 inch square) negatives, and one looked very similar to the post card. I scanned it, but the image had some lens flare across a bagpiper’s face so I dismissed it. I did noticed, however, that a bass drum in the upper left corner had on its skin: “Carnegie Tech Kiltie Band.” It was the last negative on a roll of film—the only image of the group on the mountaintop—and it’s not like Hugh Morton to command a group of people to very tip of the mountain only to make one exposure. So I went back to the box to see if there was another envelope from 1961. There was, labeled “Highland Games ’61”; it did not, however, have any more images of the band.

I started my search anew for a different image. Further down in the box was a blank envelope on which Elizabeth had penciled a note: “H.G. late 50s-e.60s.” (That’s archivist talk for Highland Games, late 1950s or early 1960s). I peeked inside and saw three 4×5-inch black-and-white negatives and some 120 negatives. Wouldn’t you know it? One of the 4×5 negatives was the Carnegie Tech Kiltie Band. I scanned that negative and prepared it for loading onto the blog, cropping the image to my liking.

For my post, I wanted to link to the Durwood Barbour postcard and draw your attention to that project, which includes several Hugh Morton postcards. I searched for the image and found it. Would you believe the postcard in the Durwood Barbour collection shows the very same Carnegie Tech Kiltie Band?! The postcard doesn’t state that, nor the date of the image. We can now add that information to the postcard’s descriptive information.

Do you think there’s any coincidence that my brother graduated from Carnegie-Mellon and that my father was an assistant football coach there for twenty years? I don’t know, but if my best friend from high school calls me up one day soon and says, “I never mentioned this before, but my father played the bagpipes on Grandfather Mountain during his Carnegie Tech days,” I’m going to get the shivers.

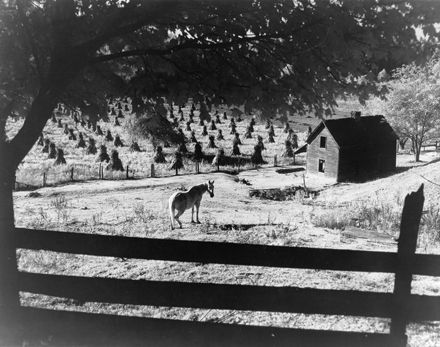

Morton the environmentalist

When my good friend who works for the Nature Conservancy in NC heard that I was going to be working on the Morton photos, she could barely contain her glee. Hugh Morton, you must understand, is somewhat of a rock star in environmental and land conservation circles. This lovely eulogy by Morton’s good friend and Appalachian State professor Harvard Ayers (a former professor of mine, actually!) details Morton’s legacy and contributions in these areas—donating thousands of acres of land on Grandfather, championing the Linn Cove Viaduct to “minimize the ecological impact of the Blue Ridge Parkway,” and making the influential 1995 documentary “The Search for Clean Air”—to name just a few.

When my good friend who works for the Nature Conservancy in NC heard that I was going to be working on the Morton photos, she could barely contain her glee. Hugh Morton, you must understand, is somewhat of a rock star in environmental and land conservation circles. This lovely eulogy by Morton’s good friend and Appalachian State professor Harvard Ayers (a former professor of mine, actually!) details Morton’s legacy and contributions in these areas—donating thousands of acres of land on Grandfather, championing the Linn Cove Viaduct to “minimize the ecological impact of the Blue Ridge Parkway,” and making the influential 1995 documentary “The Search for Clean Air”—to name just a few.

But Morton’s most powerful statements on behalf of nature were his photographs, which he used to great effect to show damage done by pollution and irresponsible development, to document rare and endangered species, and to capture rural life in NC. As these sample images illustrate, his eye for composition and remarkable ability to highlight natural features to their greatest impact made a stronger case for conservation than words could have.

But Morton’s most powerful statements on behalf of nature were his photographs, which he used to great effect to show damage done by pollution and irresponsible development, to document rare and endangered species, and to capture rural life in NC. As these sample images illustrate, his eye for composition and remarkable ability to highlight natural features to their greatest impact made a stronger case for conservation than words could have.

We would love to hear from people who worked with Morton on environmental causes or who saw him in action on this front. Did you attend one of his slide show lectures? When and where? What images stuck with you?

A processor's perspective

These views of our work areas give some idea of what it is like to process a collection as large, varied, and disorderly as the Morton photos. Since I began working on the collection two months ago, I have had regular moments of crisis during which I become nearly paralyzed by all the challenges associated with and possible approaches to this project. How do you impose order on chaos, while respecting what few pockets of order do exist? How do you decide what to digitize, and when? How do you balance the needs and interests of the many people who will use this collection with the preservation needs of the material itself?

I usually manage to calm myself with a few simple mantras:

1) In essence, all I am doing is taking one huge pile of stuff, sorting it into smaller piles, sorting those piles into smaller piles, then sorting those piles, and on and on into infinity (OK, I exaggerate) – and, finally, describing the piles. That doesn’t sound so bad . . . right?

2) By documenting carefully and making smart use of descriptive tools, we can ultimately provide access to the collection in a variety of ways – through a traditional archival finding aid, through digital images, by subject, by date, by format, etc. – offering lots of options. Then, once the collection is available, we can listen to what actual users have to say and incorporate their suggestions.

3) I will never get bored at this job. Hugh Morton crammed more into a given month than most of us do in a lifetime, e.g., saving lighthouses, fighting air pollution, attending countless sporting and political events, hanging out with celebrities, bears, and cougars, and still finding time to enjoy the really important stuff – his family and friends. I’m lucky to have this opportunity to learn from and get to know him through the images he created.

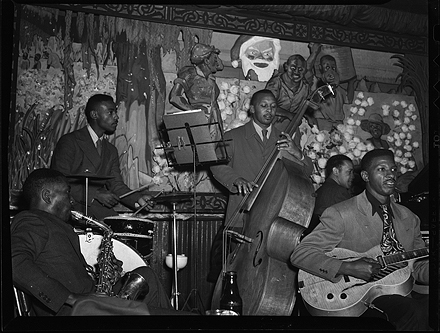

New Orleans, 1945

Why feature photographs made in New Orleans in 1945 by a North Carolina photographer? Because they are great examples of the hidden riches that await us! They also serve as good samples to explore the far reaches of blogging on the Internet as an aid in processing a photograph collection. Plus, Hugh Morton loved jazz.

The Daily Tar Heel, UNC’s student newspaper, ran an article on Sunday, 27 September 1942 about Morton’s return to campus to photograph the prior day’s football game for the paper before his Tuesday entrance as a technical sergeant in the Army’s photography division. The feature also noted that Morton reminisced on how he “got his start at Carolina by taking pictures of Hal Kemp, University alumnus.” James Hal Kemp (1904-1940), who attended UNC from 1922 to 1926 but did not graduate, was one of the most noted “sweet-swing” band leaders of the 1930s. (Kemp’s papers are in the Southern Historical Collections in Wilson Library). The article stated that Morton was so pleased with his photographs that, “He now has pictures of every nationally known band in the country with over 100 snaps of Benny Goodman, some of which have appeared in Downbeat, music magazine.” We’ll be keeping all four of our eyes open for those.

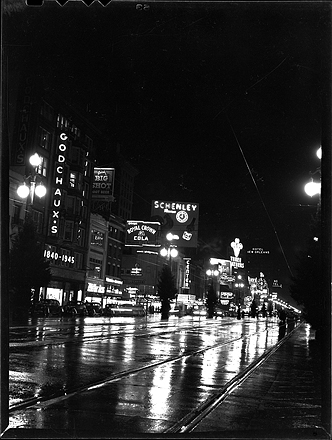

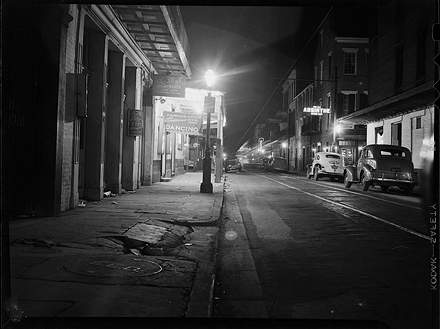

The photographs featured in this post are found in an envelope that contains twenty negatives and is labeled, simply, “New Orleans.” One of those negatives is a night scene looking down Bourbon Street. On the right is the The Old Absinthe House Bar and farther down the street is Club Bali; on the left is the Famous Door Cocktail Lounge. The automobile license plates on the right are dated 1945, confirming the date on Godchaux’s marquee in the image above.

What was happening with Hugh Morton in 1945? He was wounded in March, a few days after photographing General Douglas MacArthur reviewing the 25th Division on New Caledonia, and received his honorable discharge from the United States Army on 30 June. He married Julia Taylor on 8 December.

Within the batch of New Orleans negatives are a few outdoor scenes depicting a couple wearing longer coats, suggesting he was there during a colder time of the year. Duke University’s football team defeated the University of Alabama in the Sugar Bowl on January 1st. Perhaps Morton was there to photograph the football game? Thus far we’ve not located any negatives of that event. Maybe he was on leave? One negative depicts a group seated in a hotel room: Morton in civilian clothes, another man in a military uniform, and two women.

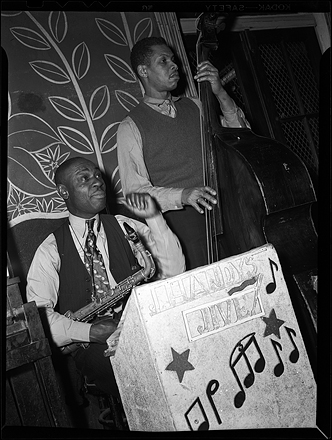

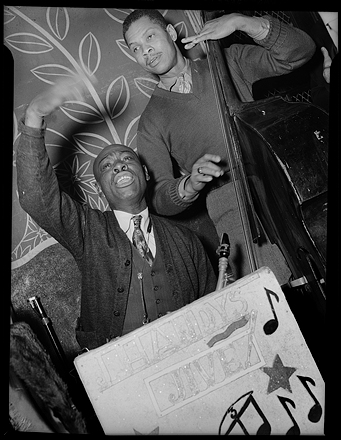

Whatever the date of his visit, Morton headed to the jazz clubs with camera in hand and he photographed three performances. Only one set is identifiable from the content: two negatives of Captain John Handy (1900-1971) and an unidentified upright bass player.

A second setting records another group, apparently a quintet, the only recognizable character being the bopping Santa above the stage backdrop. Santa says it might still be around New Year’s Day.

To round out the photographs of jazz musicians, here’s an unidentified piano player in what appears to be yet a third club setting:

Any jazz historians out there who can place a name to some of these unnamed faces?

From Grandfather Mountain to Chapel Hill

The life’s work of photographer Hugh Morton has a new home: the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives in Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It took two trips in four vans filled to the gills to bring it all from the Morton residence near Grandfather Mountain to the university where Morton spent his freshman through junior years as a student. His enlistment in the United States Army in September 1942, at the outset of his senior year, pulled him away to the Pacific and on to what became a celebrated life, but he returned to the campus he loved time and time and time again—and likely always with his camera.

It’s also likely that Morton had his camera with him everywhere else he went. We all look for something to “click” in our lives; for Hugh Morton it was his cameras’ shutters. We think he clicked them about half a million times. It takes a lot of shutter clicks to fill four vans. Morton made many photographs and shot a lot of motion picture film, too. It will take a good deal of time—measured in years—to organize and make available for use the results of so much clicking. Sometimes I “shutter” just thinking about it.

There is so much interest in the Morton collection. The first inquiries started before we opened more than a handful of boxes. The time needed to make such a voluminous collection available compared to the demand for its use beckoned for a non-traditional approach to collection processing. The way it’s “supposed” to be done is to open the collection only once it is completed. To make material accessible as soon as possible, we are planning to make parts of the collection available incrementally as we complete them.

We also needed a way to keep people informed about our progress and offer glimpses into the collection’s wealth. We are enthused by the public interest and want to transform it into community involvement. So we developed this blog to meet those needs and we hope it “clicks” with you!