This Month in North Carolina History

On February 10, 1885, the state of North Carolina legally recognized the identity of the “Indians of Robeson County,” a milestone in the history of the tribe now known as the Lumbee. One scholar has identified no fewer than seven theories about the origins of the Lumbees, many of which are still debated today. In fact the law of 1885 referred to them as Croatan Indians, reflecting the idea that they descended from the settlers of the “Lost Colony.” Over the years, the Native American community in southeastern North Carolina, who usually referred to themselves as “Our People” or “the Indians,” adopted an old version of the name of the river on which their ancestors had settled, Lumbee.

In the increasingly polarized racial environment of the ante-bellum south, the Lumbees found it difficult to maintain their identity as Native Americans. Since they were not a recognized tribe, they were pushed to declare themselves either white or free persons of color, neither of which was acceptable to them. The situation became acute after the Civil War when, in 1875, North Carolina began building a new, racially segregated, public school system. No schools were planned for Native Americans, and Lumbees faced the choice of giving up their Native American identity or denying public education to their children. The next ten years—”the decade of despair” for the Lumbees—ended when Hamilton McMillan, a representative from Robeson County, shepherded through the General Assembly a bill recognizing the Lumbees legally and providing for public schools for their children.

Thus there emerged in Robeson County a rare three-part public school system providing schools for white, African American, and Native American children. By the time Robeson County schools were integrated in 1970, separate educational facilities for Native Americans were provided at the grammar school, junior high school, and high school levels. In 1887 the General Assembly provided money for the establishment of an Indian Normal School to train teachers for the Native American public schools. In 1941 it became Pembroke State College for Indians and is now the University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

Today the Lumbees are the largest Native American tribe in North Carolina and one of the largest in the country. Building on their recognition by the state, Lumbees have attempted for years to gain full federal recognition as a tribe. In 1987 they submitted a three-volume petition to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Representatives from North Carolina in the U.S. Congress have also introduced a number of bills to grant direct federal recognition to the Lumbees, but the tribe remains formally recognized only by North Carolina.

Sources

Adolph L. Dial and David K. Eliades.

The Only Land I Know: A History of the Lumbee Indians. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, c. 1996.

Gerald Sider. Living Indian Histories: Lumbee and Tuscarora People in North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, c.1993, 2003.

Vernon Ray Thompson. “A history of the education of the Lumbee Indians of Robeson County, North Carolina from 1885 to 1970.” Ed. D. diss., University of Miami, 1973.

Robert K. Thomas. “A report on research of Lumbee origins.” [1976?]

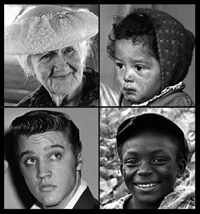

I should point out that we are aware that Elvis Presley was not a North Carolinian. Nonetheless, there is a fantastic early portrait of him in “Carolina Faces,” an exhibit of photographs by Don Sturkey on display now in the North Carolina Collection Gallery. The Elvis photograph shows the young singer outside of the Charlotte Coliseum before a concert there in 1956.

I should point out that we are aware that Elvis Presley was not a North Carolinian. Nonetheless, there is a fantastic early portrait of him in “Carolina Faces,” an exhibit of photographs by Don Sturkey on display now in the North Carolina Collection Gallery. The Elvis photograph shows the young singer outside of the Charlotte Coliseum before a concert there in 1956.