This Month in North Carolina History

At their annual meeting in April 1854, the stockholders of the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road Company celebrated the completion of their wooden highway. The longest plank road ever built in North Carolina, the Fayetteville and Western stretched 129 miles from the Market House in Fayetteville to the village of Bethania near Salem in Forsyth County. The Fayetteville and Western and a number of other plank roads chartered in North Carolina in the 1850s, were built in response to the miserable condition of overland transportation in the state during the first half of the nineteenth century. Public roads in general were little changed from colonial days. Rutted and rough in good weather, rain turned them into nearly impassable stretches of mud and gloom. Published travel accounts from the period complained bitterly about North Carolina’s horrible roads and blamed them for the state’s economic and social backwardness.

At their annual meeting in April 1854, the stockholders of the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road Company celebrated the completion of their wooden highway. The longest plank road ever built in North Carolina, the Fayetteville and Western stretched 129 miles from the Market House in Fayetteville to the village of Bethania near Salem in Forsyth County. The Fayetteville and Western and a number of other plank roads chartered in North Carolina in the 1850s, were built in response to the miserable condition of overland transportation in the state during the first half of the nineteenth century. Public roads in general were little changed from colonial days. Rutted and rough in good weather, rain turned them into nearly impassable stretches of mud and gloom. Published travel accounts from the period complained bitterly about North Carolina’s horrible roads and blamed them for the state’s economic and social backwardness.

Plank roads, essentially, were highways paved with wood. They appeared to offer several advantages over both stone-paved roads and railroads. They were much less expensive to build and maintain than railroads or roads paved with stone. They could reach small towns and rural areas where rail service was impractical, and they were comparatively quick to build. The state encouraged the building of the Fayetteville and Western by agreeing to invest $120,000 in the company (3/5ths of its stock) if private investors could raise the remaining $80,000. This was quickly done and in October 1849 construction began.

In building the plank road, the Fayetteville and Western first graded, crowned, and compacted the roadbed. Crews dug drainage ditches on either side. Four lines of sills, five by eight inches, were embedded in the prepared road. Eight foot long planks, four inches thick and eight inches wide were laid across the sills and covered with sand. This formed an eight foot wide wooden track which took up roughly half of the road bed. The other half was left so that wagons would have a place to turn off the wooden track when passing. Loaded wagons remained on the wooden surface while empty wagons or carriages moved to the unpaved section. The company built toll houses and gates every eleven miles. Construction costs for the first 88 miles of the road were about $1470 per mile and were in line with costs for building other plank roads.

Revenue for the Fayetteville and Western came from a graduated schedule of tolls. A horse and rider paid one half cent per mile, and wagons paid tolls from one cent to four cents per mile, depending on the number of horses pulling them. Realizing the importance of accurate and honest toll collection, the company made an effort to find reliable toll keepers and paid them $150 a year.

Initial response to the road was enthusiastic, and for the first several years revenues grew. The road was particularly popular with stage coach companies and their passengers. The trip from Fayetteville to Salem, which had previously taken as long as three days, required 18 hours over the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road. The success, however, was more apparent than real. Competition with the railroads, particularly the North Carolina Railroad, was more damaging to the plank road company than its directors had anticipated. Increasingly, users of the road avoided toll stations, bypassing them on older country roads. The most serious problem, however, related to maintenance. The directors of the Fayetteville and Western, based on the experience of plank road companies in Canada and New York State, expected a life span for their road of ten years. Plank roads in North Carolina, however, deteriorated much more quickly, and the road needed replacement after five years. The company had not budgeted for anything like such an expensive maintenance schedule, and by the mid-1850s, revenue was no longer keeping up with expenses. The Civil War, which put a great strain on the road system and disrupted trade and finance, put an end to the struggling Fayetteville and Western, which was abandoned and forgotten.

Sources:

Report of the Board of Internal Improvements of the Legislature of North Carolina: at the session of 1850-51. Raleigh, NC: Thos. J. Lemay, Printer to the State, 1850.

John A. Oates. The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear. Fayetteville, NC: Fayetteville Woman’s Club, 1981.

Robert B. Starling. “The Plank Road Movement in North Carolina,” North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 16: 1 and 2 (January and April, 1939).

Alan D. Watson. Internal Improvements in Antebellum North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 2002.

Image Source:

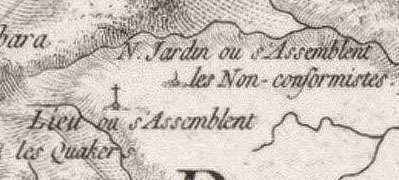

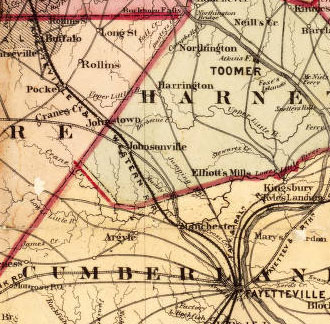

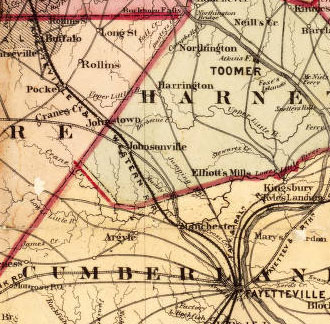

Detail from Pearce’s new map of the state of North Carolina: compiled from actual public and private surveys. Raleigh, NC: Pearce & Williams, 1872. Cm912 1872p.