A couple of year ago I had the pleasure of writing a “This Month in North Carolina” feature on Dr. John R. Brinkley, a famous or maybe infamous, son of Jackson County, North Carolina. Brinkley made himself a millionaire, in the teeth of the Great Depression, performing an operation which he claimed transplanted goat glands into men to restore virility. I noticed the other day that our copy of Dr. Brinkley’s Doctor Book was being sent to the Library’s Conservation Laboratory for restoration work. Published by Brinkley around 1933, the Doctor Book described and promoted his practice and hospital in Del Rio, Texas. Del Rio is on the Rio Grande, and I have always wondered if Brinkley located there, at least in part, because it was so handy for sudden trips out of the country. At any rate, the Doctor Book is a good example of an item to which no importance was attached when it was published because it was little more than a piece of advertising. As a consequence, our copy is one of the very few left, and it has become very important because of its connection with the history of medicine, or perhaps medical fraud, in the United States. I am pleased to report that our copy is in pretty good shape. The paper has held up well, but the cover has become detached. In my brief study of the life and times of Dr. Brinkley, I enjoyed looking through the Doctor Book. I particularly remember the advice to prospective patients to “bring cash, the Doctor does not take checks.”

Month: August 2009

August 1831: North Carolina and Nat Turner

This Month in North Carolina History

Beginning in the early hours of Sunday, 21 August 1831, a slave named Nat Turner led about sixty followers in a series of attacks on white families in Southampton County, Virginia. By the time local militia had suppressed the insurrection some 48 hours later more than fifty people had been killed.

The shock waves from Turner’s attack were felt all over the South. Counties in North Carolina were just over the state line from Southampton, and word of the assault spread rapidly along the border. Rumors grew by leaps and bounds as they traveled.

As refugees from Virginia poured into Murfreesboro, North Carolina, a band of rebellious slaves was reported to be within six miles of the town. The militia was called out in Hertford, Halifax, and Northampton Counties. North Carolina’s Governor Montford Stokes was bombarded by reports of violence and requests for weapons. In Edgecombe, Gates, and Chowan Counties white people armed themselves and closely monitored the behavior of their slaves.

As news of Turner’s insurrection spread, reaction began to crop up in areas relatively far removed from the North Carolina-Virginia line. In Duplin, Sampson, and New Hanover Counties, more than a hundred miles from the scene of Turner’s attack, a situation near panic ensued. Frightened by rumors, most of the citizens of the area convinced themselves that there was a general plot among their slaves to rise up and massacre the white population.

Confessions extorted from slaves under torture became the basis for arresting even more slaves who were similarly tortured until they confessed. Wild stories were everywhere. At one point, the town of Clinton in Sampson County was reported burned to the ground and dozens of white families killed. Kenansville in Duplin County braced for an attack by an army of more than 1500 slave insurrectionists. Wilmington in New Hanover County was thrown into a panic by the discharge of a cannon north of the city, and citizens passed a night of near hysterical fear.

Investigation the next day revealed that the gun had been fired by a carousing group of white men. Eventually news of the events in Virginia reached even the far western counties of North Carolina. In Rutherford County, slaves who worked local gold mines were feared to be plotting an uprising.

None of the many rumors of murderous slave insurrections which circulated in North Carolina in August and September of 1831 proved to be true. Terror and death were very real, however, for the state’s African American population. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of slaves or free blacks were arrested, and many were tortured and killed in areas where white peoples’ fear turned into panic and then into violence. Black North Carolinians paid a heavy price for the revolt of Nat Turner.

Sources:

Charles Edward Morris, “Panic and Reprisal: Reaction in North Carolina to the Nat Turner Insurrection, 1831,” The North Carolina Historical Review, January 1985 (Volume 62, no. 1).

Robert N. Elliott, “The Nat Turner Insurrection as reported in the North Carolina Press,” The North Carolina Historical Review, January 1961 (Volume 38, no. 1).

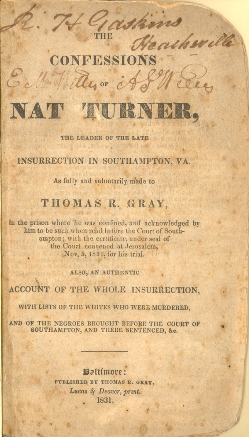

Image Source:

Nat Turner. The confessions of Nat Turner…. Baltimore : T.R Gray, 1831 ([Baltimore] : Lucas & Deaver).