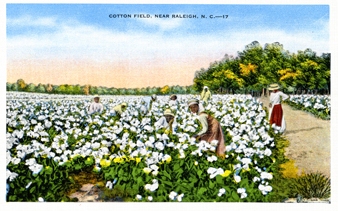

“To combat agricultural depression and the hand-to-mouth cash crop system, North Carolina has been conducting what its able Governor Oliver Max Gardner calls a ‘Live-at-Home’ campaign. The economic theory is that the home-living husbandman raises his own food and feed, patronizes local production plants, reduces his dependence upon extrastate sources of supply. [Included in the campaign] was an essay contest among 800,000 North Carolina school children. Last week Governor Gardner awarded prizes in the House of Representatives.

“Before him, crowded cheek to jowl, sat whites and blacks, men and women, boys and girls, for the ‘Live-at-Home’ movement included Negroes. Newsmen remarked with astonishment upon the sudden evaporation of race prejudice. Negroes spoke from the same rostrum as Governor Gardner about the ‘recovery of their race’s self-respect.’

“To Leroy Sossamon, blond and blue-eyed, of Bethel High School and to Ophelia Holley, chocolate brown, Governor Gardner awarded two silver loving cups for their essays. Then, with them, he walked out before the statue of Governor Charles Brantley Aycock to be photographed. His political friends, suddenly apprehensive, reminded him that no southern Governor had ever had his picture taken publicly with a Negro, warned him that such a photograph would be used against him in future campaigns. Undaunted, Governor Gardner ranged the black girl on his right and the white boy on his left, ordered the photographer to proceed. Said he: ‘If I ever get into politics again, I’ll use this picture for myself.’ ”

— From Time magazine, July 7, 1930