This Month in North Carolina History

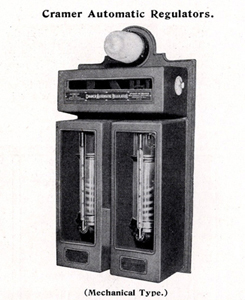

The small hand of the clock pointed to 10 as Stuart Cramer stood before the 600 or so people assembled for the American Cotton Manufacturers Association’s annual conference in Asheville’s Kenilworth Inn on May 17, 1906. It was the second-day of the association’s 10th annual meeting and Cramer, already established as a leading designer of cotton mills in the South, was on the agenda as the day’s first speaker. He was scheduled to discuss the Automatic Regulator, one of his most recent inventions and a device designed to allow for automatic control of humidity and temperature within cotton mills.

The small hand of the clock pointed to 10 as Stuart Cramer stood before the 600 or so people assembled for the American Cotton Manufacturers Association’s annual conference in Asheville’s Kenilworth Inn on May 17, 1906. It was the second-day of the association’s 10th annual meeting and Cramer, already established as a leading designer of cotton mills in the South, was on the agenda as the day’s first speaker. He was scheduled to discuss the Automatic Regulator, one of his most recent inventions and a device designed to allow for automatic control of humidity and temperature within cotton mills.

“At first sight,” Cramer began, “the title chosen for this paper seems to be rather comprehensive when it is considered that I intend to limit my remarks largely to the description and application of my new Automatic Regulator.” The five words he chose for the title of his talk were unremarkable by themselves. But two of them in combination would brand one of the biggest technological innovations of the 20th century–an advance that would allow factories and office buildings to keep their windows closed year-round and would contribute to the decline of front porch life in the South. Cramer spoke for thirty minutes on “Recent Development in Air Conditioning.”

Cramer could not lay claim to being the first to develop methods for simultaneously cooling, dehumidifying, circulating and cleansing the air. Credit for that development is generally given to Willis Haviland Carrier, a Cornell-trained engineer. The system he installed at a Brooklyn, N.Y., printing company in 1902 controlled humidity and temperature by pumping air at a regulated speed over coils refrigerated at a set temperature.

Carrier’s invention would find a receptive audience in the South, where cotton mill owners struggled to control the temperature and humidity in their factories. And it was those issues that Cramer sought to address during his speech to those assembled at the Asheville meeting.

“In building and equipping of mills, you are accustomed to consider heating and humidifying separately, without regard to that interdependence which is so strikingly brought to notice upon even the crudest effort at hand regulation,” he said. “And the moment you attempt the refinement of automatic regulation, you are confronted with another problem, and that is ventilation. Parenthetically, I would also mention air cleansing, which, however, is a problem largely solved by an efficient humidifying system. And so, I have used the term ‘Air Conditioning’ to include humidifying and air cleansing, and heating and ventilation.’ ”

Cramer was 38-years-old when he delivered those lines. He was born in Thomasville and educated at the U.S. Naval Academy, where he studied naval engineering. Upon graduation in 1888, he resigned his commission and headed to New York City, where he spent a post-graduate year studying at Columbia University’s School of Mines. Cramer returned to North Carolina in 1889 to assume the position of chief assayer at a United States Assay office in Charlotte, more commonly known as the Charlotte Mint. Four years later, in 1893, Cramer left the Assay office to become chief engineer for D.A. Tompkins Company, a Charlotte textile equipment manufacturer.

Cramer was 38-years-old when he delivered those lines. He was born in Thomasville and educated at the U.S. Naval Academy, where he studied naval engineering. Upon graduation in 1888, he resigned his commission and headed to New York City, where he spent a post-graduate year studying at Columbia University’s School of Mines. Cramer returned to North Carolina in 1889 to assume the position of chief assayer at a United States Assay office in Charlotte, more commonly known as the Charlotte Mint. Four years later, in 1893, Cramer left the Assay office to become chief engineer for D.A. Tompkins Company, a Charlotte textile equipment manufacturer.

Cramer was quick to see opportunity in textile manufacturing, which experienced rapid growth in the Carolina piedmont between 1880 and 1915. In 1895 he left D.A. Tompkins and set out on his own, opening a Charlotte office that specialized in the design and construction of mills. Cramer also served as the local agent for several manufacturers of textile mill equipment. He is credited with planning or equipping nearly one-third of all cotton mills in the South between 1895 and 1915.

Among Cramer’s notable designs is the Highland Park Number 3 mill in north Charlotte, which opened in 1903. The facility was a full-service spinning and weaving mill and considered state-of-the art. It served as a prototype for textile mill design and construction throughout the South. And, at 250,000 square feet, the mill was also the largest in Mecklenburg County.

In addition to designing and building mills, Cramer also developed techniques to increase mill efficiency. He is credited with 60 patents, many of which were for devices to achieve such a goal. Cramer pushed for mill owners to abandon the use of a central power plant, which powered all machinery through a maze of connected belts and shafts. Instead, he suggested, each machine should include its own motor and operate as an independent electric device. His push for the use of electric power and reliance on a network of power grids made him a natural ally with industrialist James B. Duke. Consequently when Duke Power Company was formed, Cramer became a director.

Cramer’s 1906 speech to the American Cotton Manufacturers Association was a much-abbreviated discussion of the topics he addressed in the fourth volume of his Useful Information for Cotton Manufacturers. The multi-volume handbook was first published in 1904 as an advertising vehicle for Cramer’s mill design firm. But, chocked with information about mill equipment, mill design, power generation and, of course, air conditioning, Cramer’s work quickly became a general reference source for textile industrialists. It was republished several times between 1904 and 1909.

Cramer did not limit himself to merely offering advice on mill design and operations. Over time he moved into mill ownership. He was an active investor in textile ventures and sometimes accepted shares in mills as partial payment for his design work and equipment. In 1910 he became president of one of the company’s in which he had invested, Mays Mills in Gaston County. Five years later, in 1915, he acquired controlling interest in May Mills. About the same time, Cramer renamed the mill town from Mayville to Cramerton, and in 1922 he changed the company’s name to Cramerton Mills. Cramer would remain involved with the company until his death in 1940. During that time Cramerton Mills underwent rapid and continuous growth, increasing its output more than tenfold.

Cramer did not limit himself to merely offering advice on mill design and operations. Over time he moved into mill ownership. He was an active investor in textile ventures and sometimes accepted shares in mills as partial payment for his design work and equipment. In 1910 he became president of one of the company’s in which he had invested, Mays Mills in Gaston County. Five years later, in 1915, he acquired controlling interest in May Mills. About the same time, Cramer renamed the mill town from Mayville to Cramerton, and in 1922 he changed the company’s name to Cramerton Mills. Cramer would remain involved with the company until his death in 1940. During that time Cramerton Mills underwent rapid and continuous growth, increasing its output more than tenfold.

Air conditioning would not experience such a rapid growth. Many Southern mill owners did not install air-conditioning systems until the 1930s or 1940s. And, of those that did, most only partially air conditioned their mills. Air conditioning was more quickly adopted by Southern movie theaters, which, prior to installing the new technology, were forced to close during the summer. As for cooling Southern homes, air conditioning was not commonly found in houses until the 1950s or 1960s.

Despite his coinage of a new term, Cramer’s 1906 speech drew few headlines. Instead, reporters writing about the conference focused their coverage on textile manufacturers’ agreement to not poach workers from each other and on a speech by a vice president of Southern Power, the pre-cursor to Duke Power, who spoke on “The Power Behind the South.” Indeed, it would take electricity—and plenty of it—to power the Southern mills, including their air conditioning systems.

Sources

Arsenault, Raymond. “The End of the Long Hot Summer: The Air Conditioner and Southern Culture.” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 50, No. 4 (Nov., 1984): 597-628.

Cramer, Stuart W. “Recent Development in Air Conditioning,” in Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Convention of the American Cotton Manufacturers Association, Held at Asheville, N.C. May 16-17, 1906. (Charlotte, N.C.: 1906): 182-211. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433066400650

Cramer, Stuart. Useful Information for Cotton Manufacturers. (Charlotte, N.C.: Queen City Print and Paper Co., 1909).

McGrath, Mark. “Stuart W. Cramer,” in The North Carolina Century : Tar Heels Who Made a Difference, 1900-2000, eds. Howard E. Covington, Jr. and Marion A. Ellis (Charlotte, N.C.: Levine Museum of the New South, 2002): 39-42.

McNeill, John Charles.”Stuart Warren Cramer,” in Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present, eds. Samuel A. Ashe and Stephen B. Weeks (Greensboro: Charles L. Van Noppen, 1908):81-87.

Image Source:

Air Regulator in Cramer, Stuart. Useful Information for Cotton Manufacturers. (Charlotte, N.C.: Queen City Print and Paper Co., 1909).

Portrait of Stuart Cramer in Ashe, Samuel A. and Stephen B. Weeks, eds. Biographical History of North Carolina from Colonial Times to the Present. (Greensboro: Charles L. Van Noppen, 1908):81-87.

Cramer System of Air Conditioning advertisement in Cramer, Stuart. Useful Information for Cotton Manufacturers. (Charlotte, N.C.: Queen City Print and Paper Co., 1909).