Every summer, people from around the country visit Manteo, North Carolina, to see an outdoor drama called “The Lost Colony,” a dramatization of the famous failed colony on Roanoke Island. By exploring historic North Carolina newspapers, we can see how that play began and how it became a yearly production.

On July 4, 1937, Paul Green, a professor of drama and philosophy at UNC Chapel Hill, showcased the history of Manteo as the location of the failed Roanoke Colony by staging the first showing of “The Lost Colony” at the specially-built Waterside Theatre. In 1936, Green was approached by W. O. Saunders, editor and publisher of The Daily Independent from Elizabeth City, N.C. Saunders was inspired by the Passion Play of Oberammergau, Germany, to create an outdoor drama for North Carolina, and he wanted Green to be the show’s playwright. Because 1937 marked the 350th anniversary of the birth of the first English child in North America, the lost Roanoke colony into which she was born provided a fitting subject for the production.

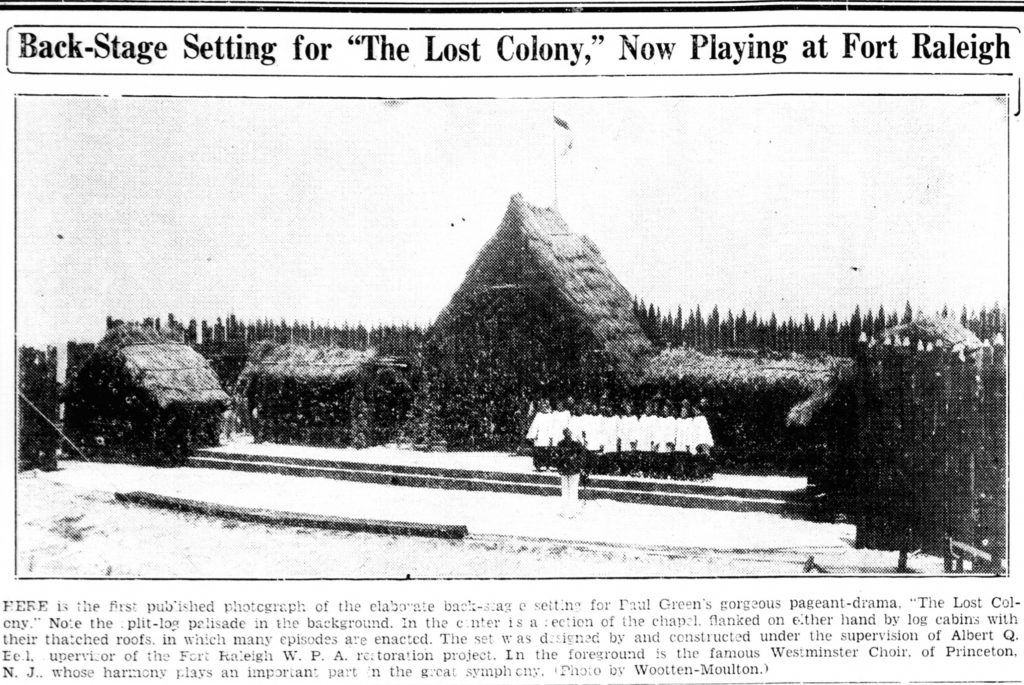

Like the play at Oberammergau, The Lost Colony took the effort of the entire community, as well as a few federal agencies, to make Manteo ready to stage the outdoor drama. The sponsors of the play partnered with the Works Progress Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Federal Theatre, the North Carolina Historical Association, the Roanoke Island Historical Association, and the Carolina Playmakers to stage the show. Those organizations provided actors, stage management, and building labor to complete the Waterside Theatre and amphitheater seating for the audience.

The Lost Colony opened to a crowd of 2000 on its first night, despite the difficult drive required to get to Roanoke Island. An early review had only positive things to say about the production value; the acting by Federal Theatre actors, Carolina Playmakers, and local residents; and singing by the Westminster Choir of Princeton, New Jersey.

A later review by the Roanoke Rapids Herald gave less favorable reviews for the accommodations provided for the audience. They noted that the town was not prepared with restaurants to feed the thousands of people who were coming to the town for the play, that the outdoor seating was uncomfortable to use for the two-hour runtime, and that parking conditions trapped attendees long after the play had finished. Despite those complaints, that review still noted the excellence of the show itself and the impressions it had made on the reviewer.

The play continued to bring large crowds to Manteo throughout the summer, the largest of which formed when President Roosevelt visited Roanoke Island to celebrate the birth of Virginia Dare. The crowd so overwhelmed the town that the hotels in Manteo and Nags Head were completely filled, so residents opened their private homes as guest lodgings.

Roosevelt’s visit brought national attention to “The Lost Colony.” By October 1937, locals were calling for the play to become a yearly production and pushing for the area to become a state park instead of “turning the site over to National Park Services.” Still, in 1941, nearby Fort Raleigh Historic Site and the Waterside Theater were transferred to the National Park Service.

Today, The Lost Colony still runs every summer at the Waterside Theater—with the notable exceptions of four years during World War II and Summer 2020, when it did not run due to COVID-19.

Additional Resources:

https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/paul-greens%C2%A0-lost-colony

https://www.ncpedia.org/fort-raleigh-national-historic-site

Green, Paul, and Laurence G. Avery. 2001. The lost colony: a symphonic drama of American history. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.