One of the first things a North Carolinian student learns is that there are 100 counties in our state. What the young student may not learn, however, is that it took over 200 years for those counties and their borders to be finalized. During that time, many counties saw the rise and fall of “dividers” within their borders who sought to add to that final accounting.

Such was the case in 1868 when, at the end of what proved to be a transformative year for North Carolina (and indeed the nation), Halifax County saw the rise of a short-lived and, for today’s researcher, mysterious division effort. The scattered, sparse evidence for this brief sentiment is best illuminated by two unique hand-drawn maps. These two maps of Halifax were drawn at nearly the exact same time: one that shows the entire county, with newly-created townships (as of 1868), while the other shows a new county called Roanoke that was to be created from the lower southeastern part of Halifax.

This post will discuss the maps, their creators, and analyze why they were drawn. Since documentary evidence for each of the maps is lacking, political and cultural circumstances swirling at the end of 1868, particularly in Halifax, will illuminate why they were created and their meaning. Information about those associated with both sides of the question of division in Halifax shows that they were likely on opposite ends of the political spectrum, with those who sought to split the county being conservative Democrats.

The map of Roanoke County

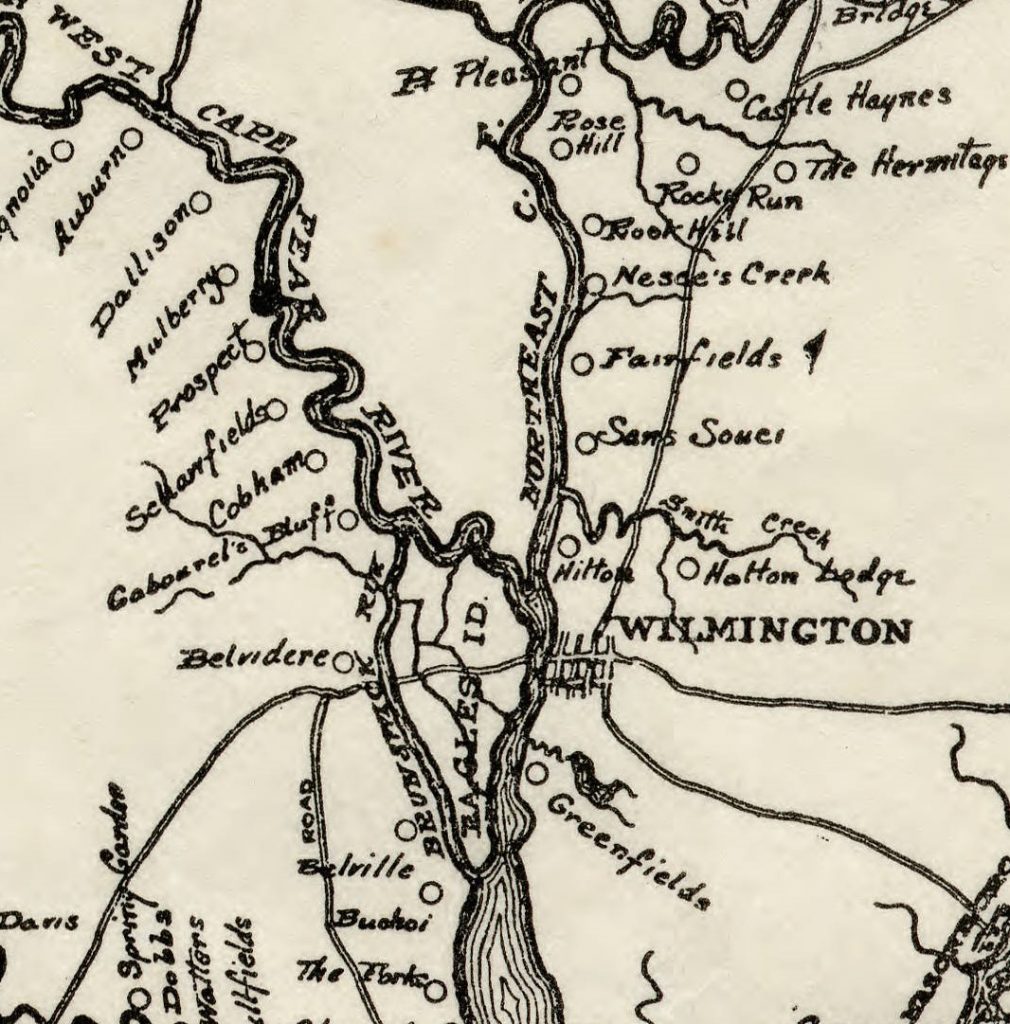

The map in question is simply rendered, entitled “Roanoke County” and signed “By ML Venable Dec 1868.” What is represented is clearly the lower southeastern part of Halifax, split from the area shown as “13 Bridges” near Enfield to the county line at Conoconnara Swamp. However, as any student of state history knows, there is no Roanoke County in North Carolina. Who drew this map, and why? And how did it end up in the North Carolina Collection?

The mapmaker, Morton Lewis Venable, hailed from a family in Oxford, Granville County, where he, like his father and brothers, worked as an educator and school administrator. Newspapers confirm that he was associated with the Oxford Male Academy and Tar River Male Academy early in his career. Work at the Vine Hill Military Academy in Scotland Neck brought Venable to Halifax County, where he was advertised as principal of the institution as early as January 1861.

With the aid of a bit of sleuthing and digging into Southern Historical Collection records, markings on the back of the map reveal more to us about its origins and ownership while providing clues as to how it came to Wilson Special Collections Library. Documentation does not exist to explain the connection between Venable and the commission of the map. However, signatures on the back reveal a clue: it was once in the hands of Dr. Eugene F. Speed and Sallie Speed. These were the children of prominent citizen John H. Speed, and the Speed family lived in Halifax and Edgecombe counties.

But rather than coming to Wilson Library via the Speeds, the map was obtained via a donation of the papers of the Smith family, specifically Peter Evans Smith. The Smiths were also prominent in Scotland Neck and the region. Peter Smith’s father, William Ruffin Smith, Jr., was heavily involved in Scotland Neck politics, serving as town commissioner for a time, and, most importantly for this question, served for many years on the Board of Trustees for Vine Hill Academy. He was also the school’s treasurer. Indeed, Vine Hill Academy appears to be the magnet that brought Venable into contact with the Speeds and Smiths.

What we can say with this information is that prominent white men around Scotland Neck in 1868 were connected to the drawing of this map of Roanoke County, and therefore involved in the question surrounding Halifax’s possible division.

The map of Halifax County

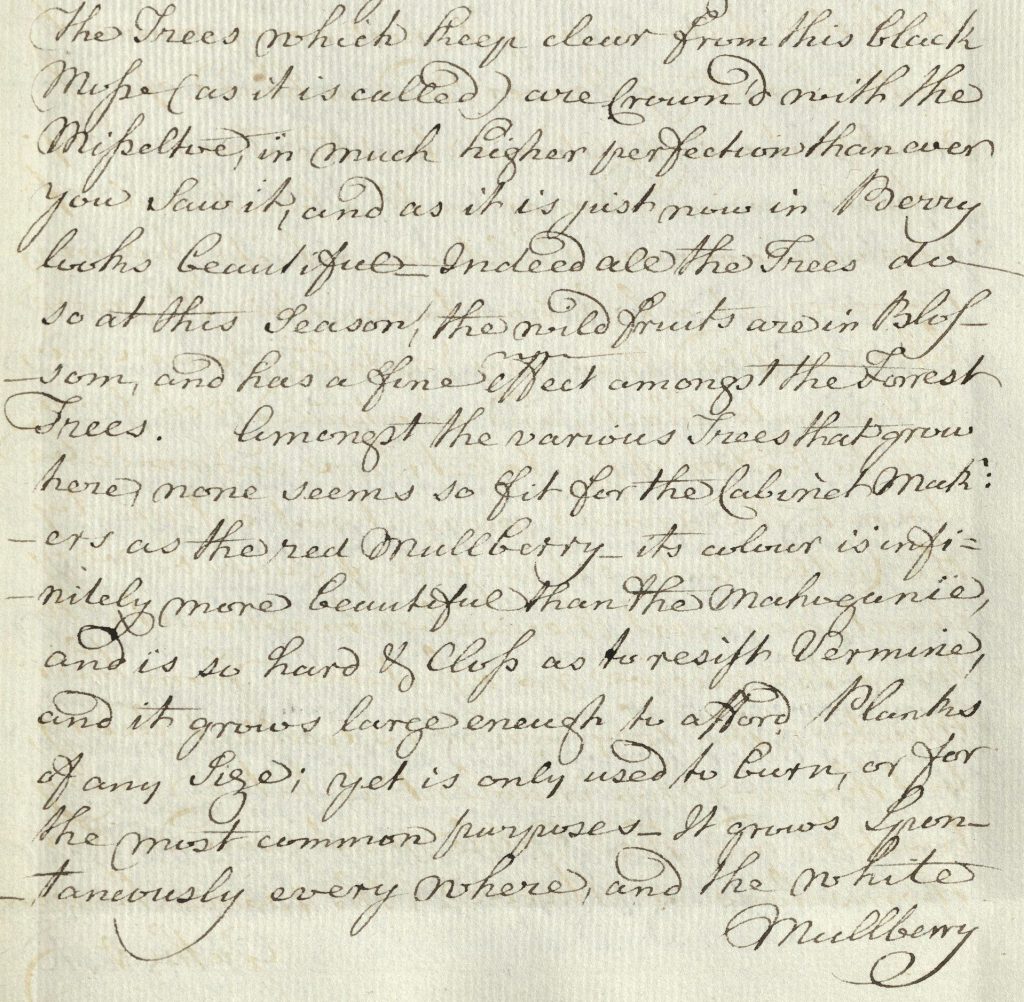

Yet another map of the area was drawn at the close of 1868, and on it, Halifax County is intact, not split. Frustratingly, only a portion of the map has survived. The inscription is revealing, though:

“A map of Halifax County made in pursuance of an Order of the Board of Commissioners of said County. Dec. 24th 1868. A.L. Pierce. This Map divides the County into eight townships supposed to be the most convenient practicable. Namely — Arcadea, Buchavia, Calidonia, Formosa, Dalmatia, [Etria], Palmyra, and Rapides, the boundaries of which are filed with this Map in the Office of the Clerk of Commissioners, and a copy of boundaries and Map also forwarded to the Secretary of State at Raleigh N.C.”

Information about the mapmaker, Albert L. Pierce, is somewhat hard to come by, but records indicate he was named Postmaster in Weldon in October 1859. Newspaper notices prove that he was elected in January 1868 as a town commissioner. In May 1868, he was elected county surveyor, although an ad for his surveying work appeared in the Weldon paper in 1856, indicating that he had been doing such work for a while.

Some pieces of information give clues to his political leanings, which could indicate which side of the division debate he stood on. One is a newspaper clipping from September 1868 where an A.L. Pierce is named President of the Grant and Colfax “Central Club” of Halifax. The notice declares that one intention of the club is to, “deprecate all the sayings, doings and actions of the copperhead Democratic party, and will try and get others to do the same at all hazards.” Another listed in this club was Charles Webb, very likely the same publisher of the antebellum paper The Roanoke Republican. Records prove another connection: Charles Webb was one also of the new County Commissioners elected in 1868.

This available information shows that the elected representatives of Halifax County were certainly not in favor of splitting the county.

What was happening in 1868?

To best understand the maps, the events of the year must be used for context. Numerous transformative political events taking place at this time included:

- The restoration of the former Confederate States to the Union, contingent upon passing new state constitutions ratifying the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed citizenship and equal protection to former slaves.

- The election of William Woods Holden, Republican, as Governor of North Carolina.

- The election of Ulysses S. Grant, Republican, as President of the United States.

The Constitutional Convention of 1868

The convention, held January – March 1868, was overwhelmingly Republican and included fifteen black delegates. The polarization of politics in North Carolina, Democrat versus Republican, was driven to a height. To say that the party divide was intractable would be an understatement: the rallying cry for the national Republican Party that year was, “Emancipation! Enfranchisement! Reconstruction!”; North Carolina Democrats were fundamentally opposed to all three.

Of special relevance to our question here about county politics: this new document also created a totally new system of townships and a Board of Commissioners for each county, with five elected seats. The new Commissioners were tasked with dividing the counties into townships and reporting back to the General Assembly by January 1869; this provides one explanation for why we have maps like these from that time. The new constitution approved in April not only enfranchised blacks, but also restored voting rights to former Confederates. The new boards gave men who had previously been excluded due to race, party affiliation, and/or wealth the opportunity to become involved in politics.

By all accounts, the enfranchisement of African Americans, which was now demanded by Congress, was a very serious threat to white conservatives. In Many Excellent People, Paul D. Escott explains that the Democratic offensive during Reconstruction was aimed at the local government: “Control of county affairs has been the foundation of North Carolina’s aristocratic social order…Reconstruction had threatened the whole system.” Considering the impact and interpretation of the new constitution provides us excellent context for the two maps of Halifax County.

Halifax County in 1868

What were the racial demographics in Halifax in 1868, and what could the changes forced by the new constitution mean for prominent white citizens of Scotland Neck? The numbers at play are important to understanding what likely drove the conversation over dividing the county. Antebellum Halifax had some of the highest numbers of slaves, but also the highest number of free blacks of all counties in the state. In 1860, black property holders in Halifax outnumbered other counties in the Roanoke Valley by sixfold. The 1870 census calculated 6,418 whites and 13,990 blacks. Black citizens also outnumbered whites in the new townships:

- Arcadia/Halifax: 604 white and 2294 black

- Buckaria: 668 white and 1114 black

- Caledonia: 503 white and 1615 black

- Dalmatia: 1009 white and 1787 black

- Ertruria: 1099 white and 1839 black

- Formosa: 903 white and 2054 black

- Palmyra: 832 white and 1513 black

- Rapides/Weldon: 800 white and 1774 black

Halifax County Board of Commissioners

Halifax County records that could illuminate the conversations and decision-making of this time, for example Board of Commissioner minutes, no longer exist.

One person on the Board is already known to us: Charles Webb, documented to be a Republican. Another way to assume the constitution of the board is to look at the Roanoke News out of Weldon, a conservative paper, who in March 1868 put forward five (Democratic) names for the new board, and none of those ended up being elected.

Walter Clark

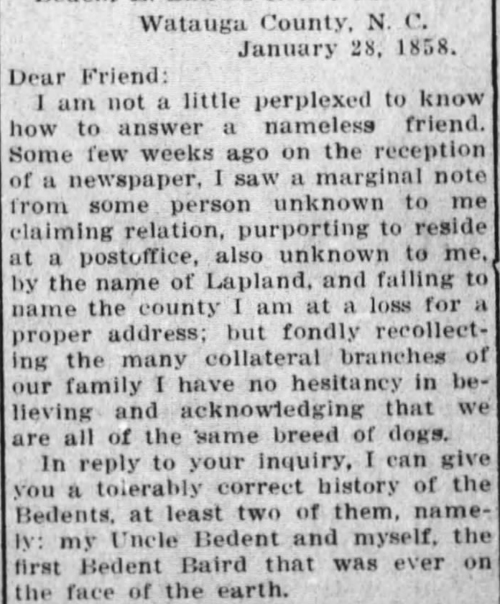

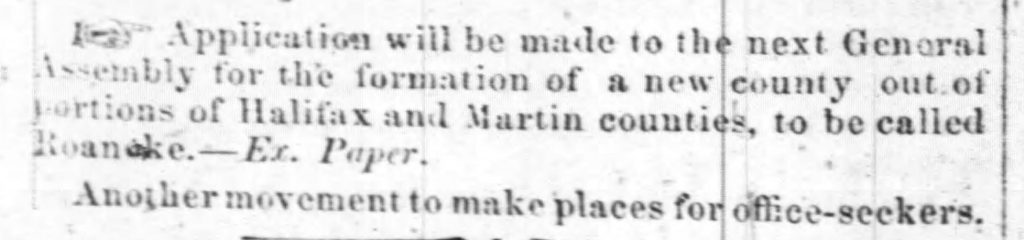

In Walter McKenzie Clark’s diaries, published in The Papers of Walter Clark, he wrote: “Nov. 18 – Went to Palmyra Meeting for formation of a new county.” An enigmatic statement, but essentially the only definitive clue that a meeting about this issue of dividing Halifax even took place. Therefore, we know that Clark was involved in this discussion, and perhaps then directly involved with the production of Venable’s map of Roanoke. Clark was also an alumnus of Vine Hill. Outside of Clark’s diary entry, only a lone, brief mention in a newspaper confirms the meeting:

Walter Clark was a prominent figure in Halifax and the state. Clark had opened a law office in Scotland Neck in 1867 and was a licensed lawyer. He would go on to become a Justice. We know from correspondence between him and prominent conservatives such as Thomas J. Jarvis and David Schenck around the time of 1868 that he was solicited to work against the “radicals” in the state Congress, specifically some of Halifax’s Republican representatives. One was John H. Renfrow, described by William Allen in his interpretation of the history of Halifax as a carpetbagger. This is another clue as to the political divisions at work when the topic of division came up: the people who were likely at this meeting shared the same political and social views as Clark.

The only people who we can say with certainty were at this meeting, in any case, were Walter Clark and (probably) M.L. Venable. But then, just as mysteriously as the subject came up, no mention of splitting Halifax came up again. Whether the proposal made it to the General Assembly, as the newspaper clipping above claims, is unclear.

Other county division initiatives in 1868

Reports in newspapers reveal that there were conversations about dividing other counties that year. March 1868 saw a petition from 1200 citizens asking that a new county be formed out of Rowan, Iredell and Cabarrus. In November, The Western Vindicator reported that “a movement is on foot looking to the formation of a new county from portion of Rutherford and Cleveland.” One that did come to fruition was the formation of Dare out of Currituck, Hyde, and Tyrrell. This was first reported in December 1868.

In his article “County Division: A Forgotten Issue in Antebellum North Carolina Politics,” Thomas E. Jeffrey says, “County division was one of the most important, and certainly one of the most enduring, of…local issues.” From the actions and debates occurring in 1868, we see this issue remained a reality throughout Reconstruction.

As with many of the other moves towards division, Roanoke County was quickly lost to history. Thankfully, though, we have one document pointing to its brief existence in the minds of some Halifax residents.