It’s been 100 years since the first war that consumed the entire world. The North Carolina Collection Gallery explores the local implications of that global war in its current exhibition, “Doing Our Bit: UNC and the Great War.” Our April Artifact of the Month, William B. Umstead’s winter service jacket, is featured in the exhibition.

William B. Umstead (1895-1954) was born on a farm in Durham County. He graduated from UNC in 1916 with a bachelor’s degree in history. After a year teaching high school history Umstead volunteered for the army when the US declared war. He saw combat in France and achieved the rank of first lieutenant.

Umstead later served as a representative in the US House, a US senator, and governor of North Carolina.

In a diary entry dated August 29, 1917, Umstead poignantly describes saying goodbye to his elderly parents before heading off to war:

Probably the saddest time I have ever spent was Mon. night. Aug 27 when I left home. I left father and mother in tears, and it almost wrung my heart from within me. To leave them, old and feeble at home alone was the most difficult task of my life. It is easy enough to go to the execution of one’s duty, when that duty can mean death, when there is no one but yourself, but to leave parents whose joy in life rests in their paternal interest in you, is the saddest and most trying of all tasks.

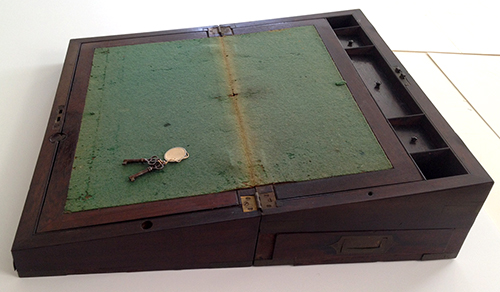

You can see Umstead’s jacket, diary, campaign hat, and UNC yearbook photo in the exhibition until June 11.