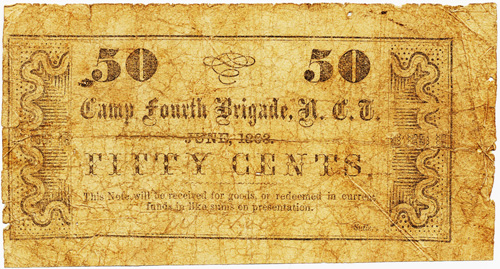

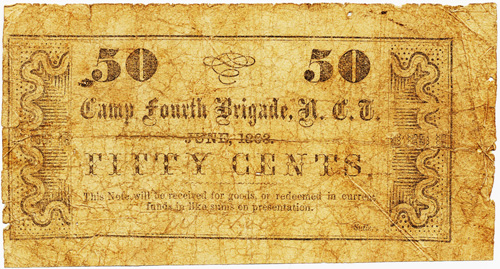

Our October Artifact of the Month, a 50-cent note, was issued by a merchant in an uncommon and now obsolete profession. The note is a rare survivor of private North Carolina paper money issued because of the Civil War.

I’ll bet many of you join me in what until recently was my ignorance of the meaning of the word sutler. The term is unfamiliar these days because sutlers are no longer needed. During the Civil War (and other wars before it), the sutler was a civilian merchant who travelled with armies and sold goods to the soldiers.

Why did sutlers exist? In our nation’s early years, federal, state, and local governments provided only limited support to institutions we now consider to be publicly-funded services. Soldiers in the military, for example, did not receive the same level of resources they do today. A soldier was expected to provide some of his own necessities and other goods to make life more livable.

A section about sutlers appears in the Confederate Army Regulations of 1863. The regulations state that “Every military post may have one Sutler, to be appointed by the Secretary of War on the recommendation of the Council of Administration, approved by the commanding officer.” Once appointed the sutler could move his wagon or tent or establish a more permanent structure near or on the grounds of an army post.

The sutler often had a monopoly on many non-military goods, including food, clothing, and stationery. As a result, prices were often unfairly inflated. And the quality of the goods, especially the food, was often very low.

Sutlers developed a less-than-respectable reputation, and were regarded as, at best, a necessary evil. Seen from another perspective, though, they operated a high-risk business, a target for local thieves and enemy army raiders.

Sutlers were important to both sides during the American Civil War. After the war ended, though, the need for sutlers diminished as the government increased the quantity and quality of its services to soldiers. The post exchange evolved to be a great benefit to the soldier, providing quality goods at desirable prices. The memory of the sutler is largely kept alive by modern self-described sutlers, merchants serving Civil War buffs with facsimile period military merchandise.

Most surviving documentation of Civil War sutlers pertains to those of the Union Army. A photo from the Library of Congress (source) shows a Union sutler, A. Foulke, and his tent at Brandy Station, Virginia, headquarters of 1st Brigade, Horse Artillery, in the winter of 1863-64.

Sutler money

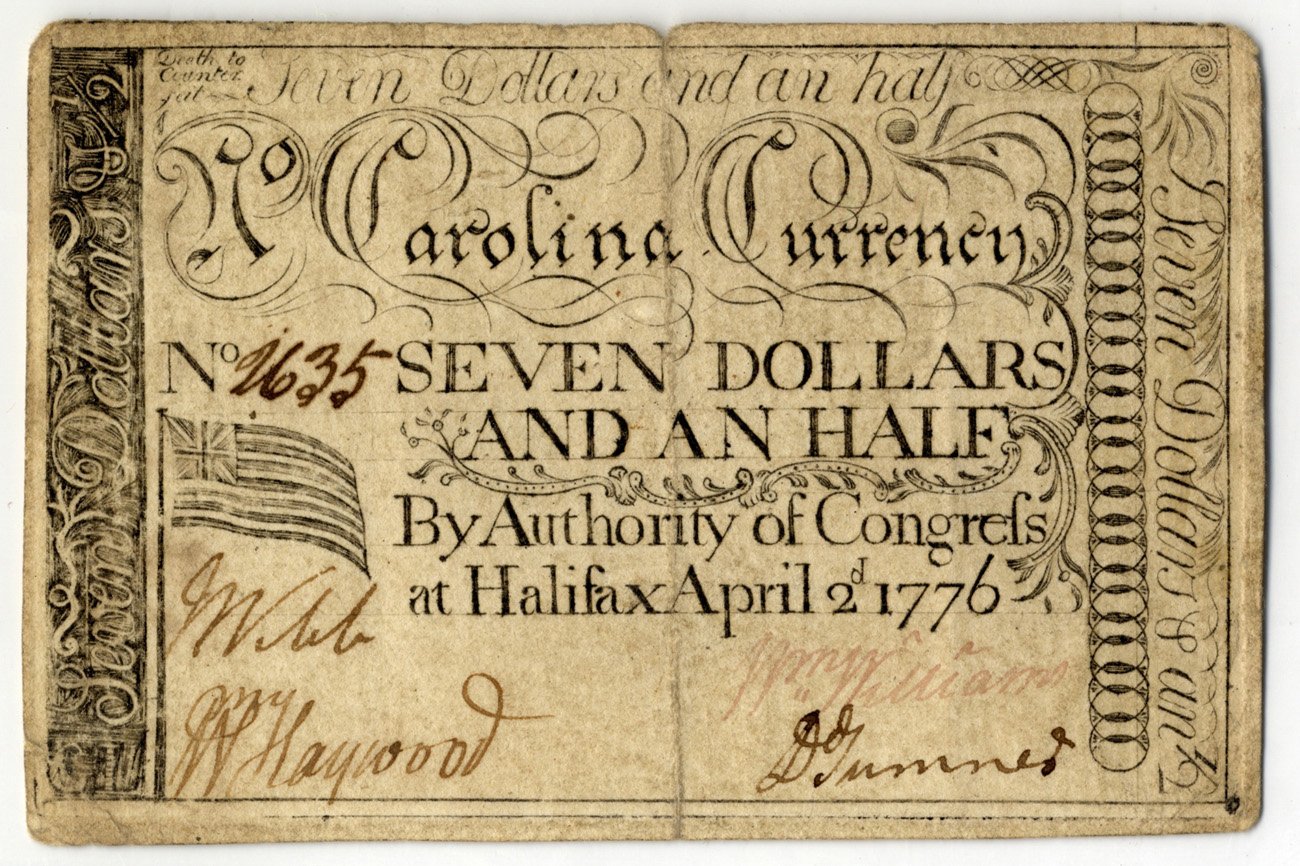

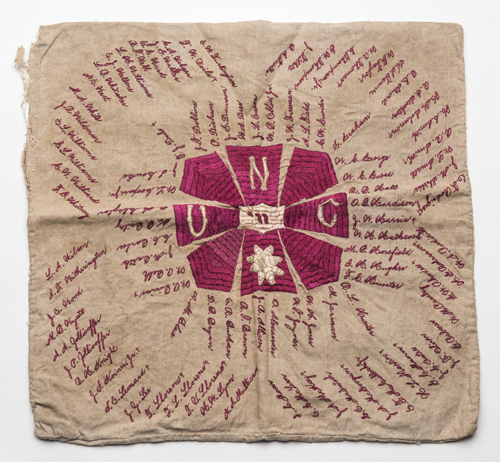

Lack of circulating money was a big problem during the Civil War. Coins were scarce, leading to private substitutes. Like many other merchants, sutlers often made small change with their own paper money or tokens. Numismatists have studied and cataloged sutler money, and most surviving Civil War examples are from Northern sutlers. Southern examples are quite rare. The North Carolina Collection recently acquired this piece of paper money from a North Carolina sutler.

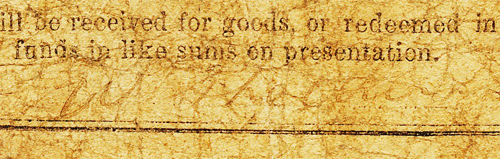

The 50-cent note is signed by W. Shelburn, indistinct here, but clearer on some of the other examples. He served the Fourth Brigade, N. C. T (North Carolina Troops). The statement of obligation declares that the note will be received for goods (from the sutler) or in “current funds,” which means any other scrip that the sutler might possess.

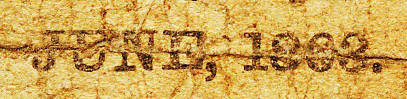

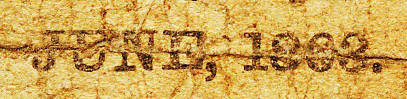

An unusual feature is the quite specific June 1863 printed date. One wonders if Shelburn had printed scrip with other dates.

Notes like this one tell an important story about the conduct of the Civil War – how militaries operated, how goods were exchanged, the life of soldiers on the front.

Can you tell us more?

The identity of W. Shelburn remains a mystery to us. We know of a William Shelburn, a North Carolina photographer active from about 1856 to 1907. It’s possible that he provided sutler services during the Civil War. But Shelburn is a relatively common name.

If you have any suggestions for identifying Shelburn, or other information about North Carolina sutlers, please leave a comment!