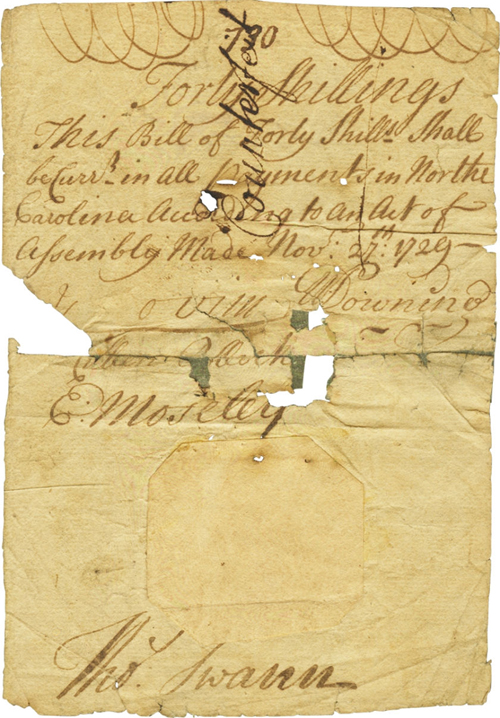

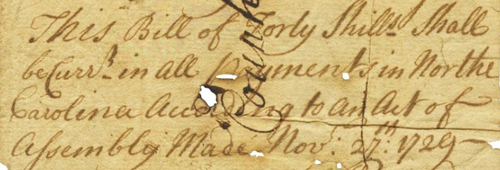

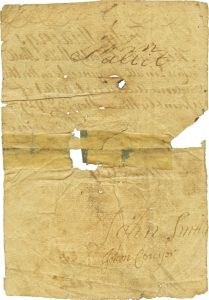

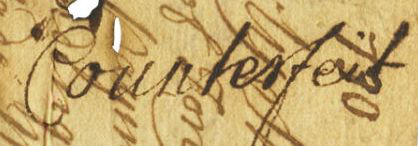

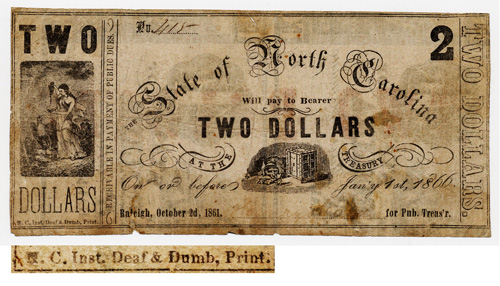

Early North Carolinians experienced many problems and frustrations with their money, and not just from having too little of it. One problem was that some of the money in circulation was fraudulent. We use this term rather than counterfeit because the problem went beyond counterfeiting — producing copies of genuine notes.

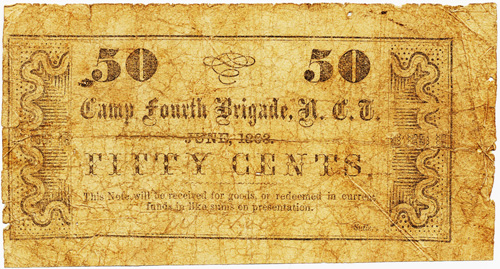

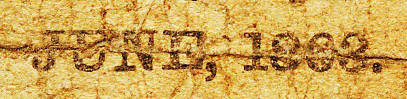

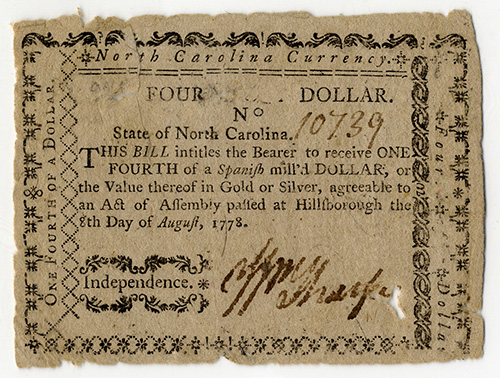

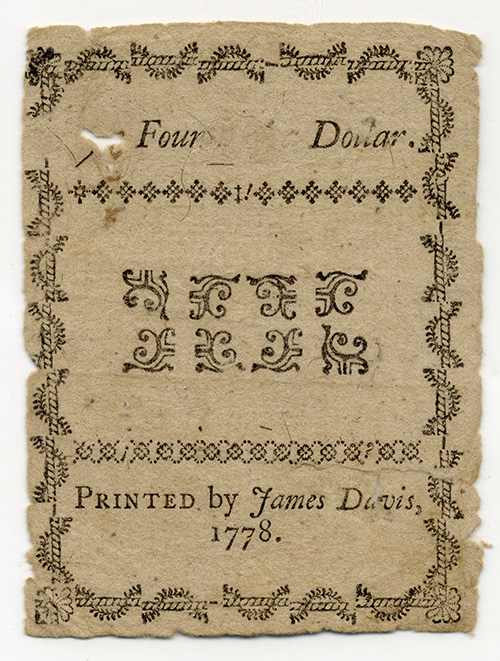

The North Carolina Collection Gallery recently acquired a “raised” note from the 1778 series of paper money. A genuine note is said to be raised when it has been altered to appear to be of higher denomination than it is.

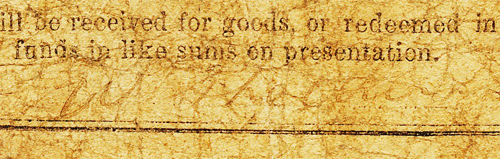

The note below, shown front and back, at first glance appears to be worth four dollars. But reading the small print on the front — the main body of text or the vertical printing to the left — reveals that the note is worth one-fourth dollar. That’s a big difference.

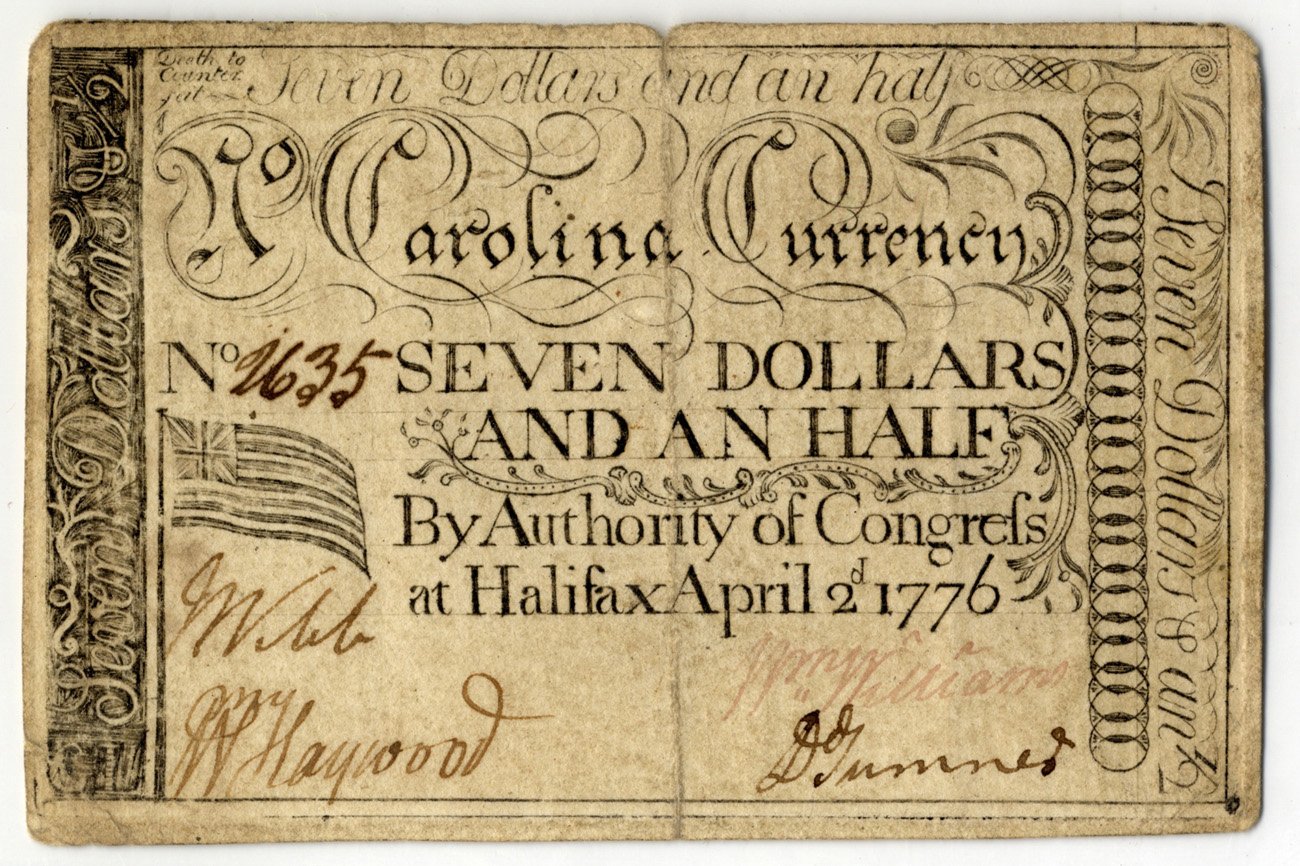

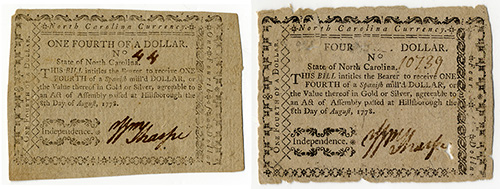

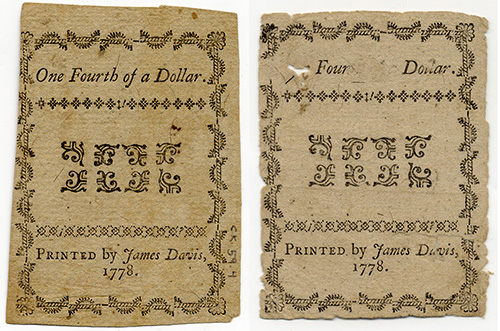

Compare the genuine but raised note to an unaltered example, below, also in our collection.

The raised note is a crude job, akin to a bad Photoshop job today.

Did it pass? Maybe.

Much paper money in circulation at the time was heavily worn, significantly more so than the relatively pristine unaltered 1778 specimen shown here. The holes and other defects produced by the raising might not alarm a person used to handling rags that had to serve well into frail old age.

Secondly, people may not have bothered to read the small print, especially if they had seen this type of note before.

Third, unusual (by present standards) denominations — such as four dollars — were more common before the Civil War, and would not have raised suspicions. And there was a genuine four-dollar note in the 1778 series, although it had a motto different from that of the quarter-dollar note.

The simple printing technology of the day, devoid of anti-counterfeiting measures, certainly did little to discourage crooks. Printing technology improved, but so did the skills of the charlatans. Raising genuine notes persisted well into the 19th century as a minor form of easy money making. Today, note raising is a seldom-encountered form of fraud. Modern crooks seem to do just fine with plain counterfeiting.