The nationwide prohibition of alcohol began 100 years ago. But the alcohol temperance movement had been fermenting in North Carolina for quite some time before that.

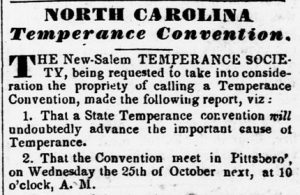

There were efforts to limit the use of alcohol in North Carolina as far back as the early 1700s, but the temperance movement didn’t begin in earnest until the 1800s. Tar Heels organized a temperance convention in 1837.

Such groups as the Order of the Sons of Temperance in North Carolina had their own newspapers, namely the Spirit of the Age. Individual temperance activists also gained national notoriety.

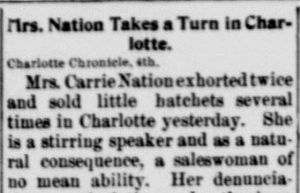

Carrie A. Nation (also spelled “Carry”) grew frustrated with the lack of prohibition enforcement in her native Kansas and became famous for taking matters into her own hands. She visited local saloons and used hatchets and rocks to break windows and alcohol bottles. Despite several stints in jail, she continued her attacks on bars, saloons, and taverns.

Nation reportedly covered her legal fees through speaking tours and selling merchandise, including miniature hatchets. Indeed, this is what happened when she visited Asheville in late 1902.

Nation reportedly covered her legal fees through speaking tours and selling merchandise, including miniature hatchets. Indeed, this is what happened when she visited Asheville in late 1902.

Although she was there to gather funds for a “home for drunkards’ wives in Kansas City,” she sold hatchets to her audience while she railed against the government “as an agent of the liquor traffic.” Because of these stunts, she was a fixture of state and national newspapers. As a member in good standing of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, she was popular among women, as well. On other occasions, she sold her books instead of hatchets.

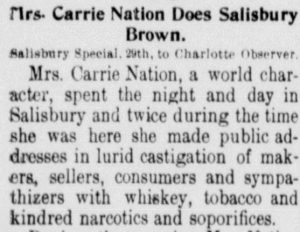

During the summer of 1907, Nation toured North Carolina, warning crowds of the dangers of alcohol, cigarettes, and more. She drew attention to societal ills and didn’t pull punches.  When she visited Salisbury on June 29, she decried drinkers and smokers alike, calling Salisbury “a hell hole” with “plenty of poverty, degradation and suffering…”

When she visited Salisbury on June 29, she decried drinkers and smokers alike, calling Salisbury “a hell hole” with “plenty of poverty, degradation and suffering…”

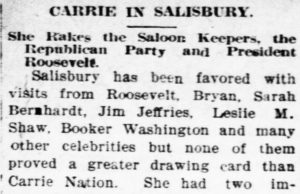

She also didn’t shy away from connecting alcohol consumption and moral decay to national politics. At one point, she said that the United States was in a “state of anarchy,” President Theodore Roosevelt was a “beer guzzling Dutchman,” and argued that there was no difference between the Republican and Democratic parties. However, she did speak kindly of North Carolina Governor Robert Glenn because of his positive attitude towards temperance.

Despite her harsh words, she drew crowds everywhere she went – from Charlotte to Hickory to Durham to Oxford. Indeed, she was always fodder for newspaper writers, one of whom said she “does not seem to be the noisy, belligerent individual she has been pictured…”

Despite her harsh words, she drew crowds everywhere she went – from Charlotte to Hickory to Durham to Oxford. Indeed, she was always fodder for newspaper writers, one of whom said she “does not seem to be the noisy, belligerent individual she has been pictured…”

Another said she was a “fanatic” yet “has an attractive face…”

Nation traveled to over half a dozen North Carolina cities during July and August 1907, speaking to delighted crowds of up to 4,000 people.

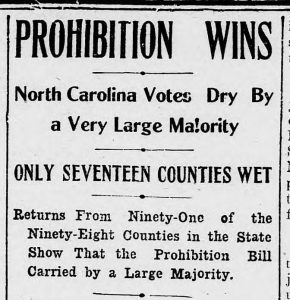

Her words likely had some effect on the state’s residents, because less than a year later, North Carolina voted to pass a state prohibition bill, the first in the country.

Prohibition won by over 44,000 votes, and went into effect on January 1, 1909. As for Carrie A. Nation, she moved to Arkansas and founded a home that she called “Hatchet Hall” before passing away in June 1911.

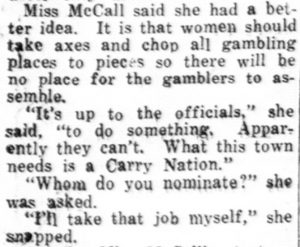

Nation left a legacy. In the 1930s, to protest the repeal of prohibition, women in Kansas pledged to keep the state alcohol-free using hatchets if necessary. Pearl McCall, a former assistant United States district attorney, urged women to take up hatchets themselves and march on Washington, destroying gambling halls in the process. She said, “what this town needs is a Carry Nation.”

Nation left a legacy. In the 1930s, to protest the repeal of prohibition, women in Kansas pledged to keep the state alcohol-free using hatchets if necessary. Pearl McCall, a former assistant United States district attorney, urged women to take up hatchets themselves and march on Washington, destroying gambling halls in the process. She said, “what this town needs is a Carry Nation.”