This Month in North Carolina History

On July 13, 1937, the first Krispy Kreme store opened for business in Winston-Salem, NC. The company’s success and quick rise to popularity were due both to the personal history of Vernon Rudolph, its owner, and the larger cultural history of doughnuts in America (and more specifically, the American South).

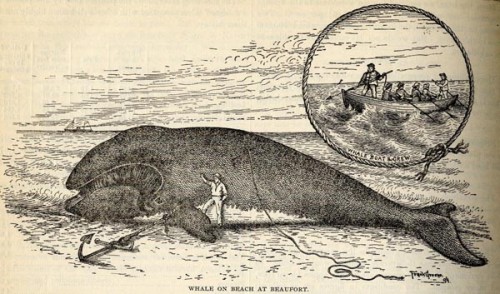

There were very few doughnuts shops in the South prior to the 1930s, and doughnut recipes that found their way into Southern kitchens were often thought of as “Yankee treats,” coming from places like Pennsylvania. However, several Southern food traditions and preferences helped pave the way for successful doughnut ventures. Bready foods such as biscuits and deep-fried snacks like hushpuppies had long been extremely popular in the region, as were other doughnut-like products, including French beignets in New Orleans.

Vernon Rudolph opened his first doughnut shop in 1933 in the town of Paducah, Kentucky, with a recipe his uncle had purchased from a chef in New Orleans. Within a few years, he had moved his business to several other Southern cities, and was focused on selling his doughnuts wholesale to local grocery stores. He still had not found the perfect location to establish his business. It wasn’t until the summer of 1937 that Rudolph set off for Winston-Salem, NC, with little more than twenty dollars in his pocket, two friends, and the intention of opening a new doughnut shop.

Why Winston-Salem? Many sources report that Rudolph was inspired by the pack of cigarettes he was smoking. He figured that a city that already supported one large industry – tobacco – would be able to support another. He also saw Winston-Salem’s early acceptance of industrialization and technology as promising, because his methods of doughnut production were mechanized. In addition he believed that a city with a large population had the potential to translate into a sizeable customer base.

The first Krispy Kreme store was located in Old Salem, across the street from the Salem Academy. After they made their rent payment, Rudolph and his partners had no money left to buy supplies and ingredients. Rudolph didn’t let this stop him, and managed to convince a local grocer to advance him the ingredients he needed in order to make the first batch of donuts, with the promise that he would soon pay the grocer back. In mid-July of 1937, the first batch of Krispy Kreme doughnuts was made.

The Krispy Kreme business model continued as it had before in Rudolph’s earlier stores, selling wholesale to local groceries. He used the Pontiac car that brought him to Winston-Salem to make his deliveries. In order to make delivering large quantities of doughnuts possible, Rudolph had to take out the back seat of the car – perhaps he could have taken inspiration from the same delivery methods that North Carolina bootleggers used during Prohibition?

However, Rudolph’s location in a busy downtown district was pumping the smell of his deep-fried donuts into an area frequented by pedestrians. They began stopping by to ask if they could purchase doughnuts for themselves rather than waiting to buy them at a store. Rudolph eventually succumbed to their demands and cut a hole in the wall so that he could sell doughnuts directly to the public fresh from the production line. The hole in the wall, which turned a wholesale operation into a retail business, had unintended consequences for how customers interacted with the business by showing them an open view directly into the production center. In addition to purveying their glazed calorie-bombs to the general public, Krispy Kreme was now selling the experience of sneaking a peek into the behind-the-scenes activities of the shop.

Rudolph used the new window into the production space to get customers’ attention. It was successful because it highlighted how clean and modern it was and introduced an element of tourism. Opening this window showed customers the machines Rudolph was using to produce doughnuts, which were definitely not old-fashioned. In fact, even the shape of a Krispy Kreme is mechanically derived: the doughnuts are formed from dough extruded by air pressure to form a perfect doughnut shape. There’s no traditional doughnut hole here! The Ring King Jr. used by Krispy Kreme stores to make doughnuts in the 1950s could make 75 dozen doughnuts in an hour.

Eventually, Krispy Kreme stores began installing their “Hot Now!” signs which lit up when fresh doughnuts were being produced in order to catch customers’ attention. At the beginning, Krispy Kreme’s business was largely focused on the wholesale market, so most doughnuts were being produced very early in the morning. As the company’s retail trade grew, it began producing doughnuts at times that were more customer friendly, with the “Hot Now!” used to draw in customers when they most wanted a doughnut.

Rudolph died in 1973 at the age of 58, but the company’s success continued to be closely tied to the spectacle of mechanical production. Even administrators of the company today refer to Krispy Kreme shops as “factory stores.” The stores were renovated again in the 1980s, creating more of a “stage” for doughnut production than a kitchen. More recently, Krispy Kreme introduced a line of coffees and espresso drinks to compete with other popular doughnut and coffee chains, which continues to encourage customers to stay and watch the doughnut production line.

Krispy Kreme has become something a cult obsession over the years, and its distinctive logo can often be found on T-shirts, thermoses, or the little paper chef’s hats you can take when you visit a store location. In 2004, NC State students developed a charity race, the Krispy Kreme Challenge, in which participants run two miles from the Bell Tower on State’s campus to the Krispy Kreme store on Peace Street, eat a dozen donuts, and run the two miles back, all within one hour.

Currently there are dozens flavors of Krispy Kreme doughnuts (not to mention their mini doughnuts and doughnut holes), but the Original Glazed has always been the most popular. The recipe that Vernon Rudolph’s uncle purchased from the French baker in New Orleans remains a secret, locked up in a safe in Winston-Salem. And while the recipe may not be available for your perusal, the corporate archives of Krispy Kreme are located at the Smithsonian Institution, as are some of the company’s doughnut-making machines from the 1950s, like the famous Ring King Jr.

Sources:

Kazanjian, Kirk and Joyner, Amy. Making Dough: The 12 Secret Ingredients of Krispy Kreme’s Sweet Success. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2004.

“Our Story,” Krispy Kreme website, accessed July 2014

Mullins, Paul R. Glazed America: A History of the Doughnut. Gainesville, FL: The University of Florida Press, 2008.

de la Pena, Carolyn. “Mechanized Southern Comfort: Touring the Technological South at Krispy Kreme,” in Dixie Emporium: Tourism, Foodways and Consumer Culture in the American South, ed. by Anthony J. Stanonis. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 2008.

Image Sources:

[Krispy Kreme paper hat], North Carolina Collection Gallery, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

“Krispy Kreme, Donut Queen,” Lew Powell Memorabilia Collection, North Carolina Collection Gallery, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.