This Month in North Carolina History

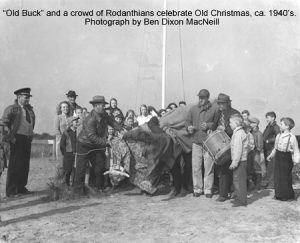

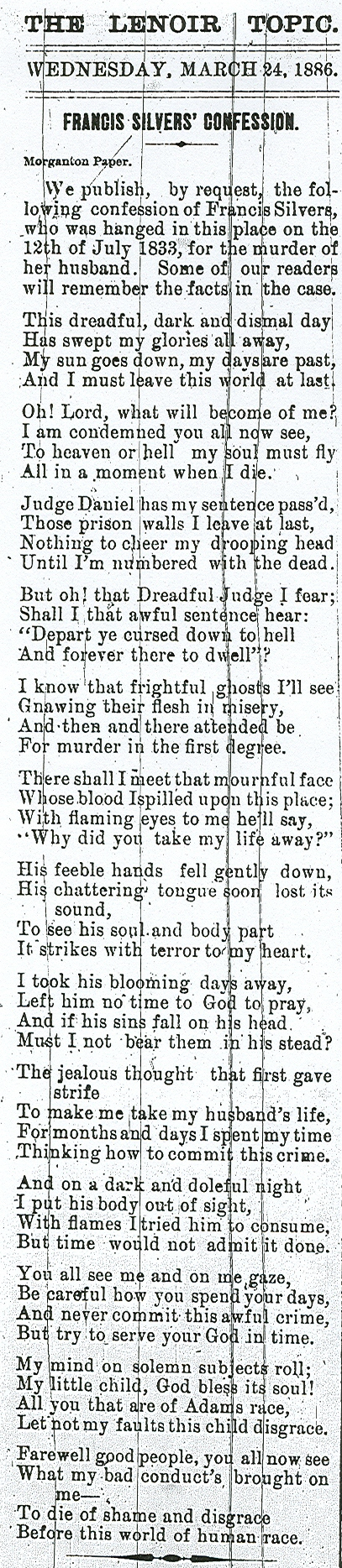

Ben Dixon McNeill covered the catastrophe for Raleigh’s News & Observer as a correspondent and photographer. His first-person accounts appeared on the newspaper’s front page for five straight days and included a retelling of his descent into the mine on May 31st. Seven photographs accompanied his articles on May 28th and 29th; the two images displayed here appeared in the latter issue with a caption that stated the photographs “need no explanation.”

The tragedy helped to speed passage of the state’s Workers’ Compensation Act, passed in 1929. North Carolina was the forty-fourth state to pass such legislation.

Historical Background

The presence of Deep River coal was first noted in print in 1820 in a letter to the American Journal of Science by Professor Denison Olmsted, chair of chemistry, mineralogy, and geology at the University of North Carolina. Olmsted, and later H. M. Chance in an 1885 report, noted that earlier uses of coal to meet local needs most likely dated to before 1775. The Deep River Coal Field is the only noteworthy source of coal in the state. There are some “sporadic deposits,” as Chance described them, in the Dan River region from the Virginia border southwest to Germanton on the border between Stokes and Forsyth Counties.

Attempts to develop commercial mining efforts in the Deep River Coal Field began during the early 1850s, and had a rocky history. The Western Railroad, chartered in 1852, was the first railroad to reach into the region. Completed in 1863, its purpose was to connect the coalmines centered at the village of Egypt (renamed Cumnock in 1895) to the riverside port of Fayetteville on the Cape Fear to the southeast. Coal was mined at three towns within a four-and-a-half mile band, all within close proximity of the Deep River: Egypt, Gulf (upstream to the west of Egypt) and Farmville (downstream and directly to the east of Egypt).

The mine at Egypt closed down in 1870 and remained flooded until 1888. Three years earlier, in 1885, H. M. Chance submitted his “Report on an Exploration of the Coalfields of North Carolina,” which identified two coal beds between Egypt and Farmville that might be worthy of thorough exploration, but doubted the likelihood of large scale production. Furthermore he did not believe further expenditures would be justified outside of the limited area. When Chance described Deep River Coal Field, he listed eight “Obstacles to Successful Mining,” he wrote:

In the Richmond coalfield great trouble has been caused by what is called spontaneous combustion. Judging from the similarity of the coals it seems possible that this same difficulty may obtain here. While this is a mere supposition, it is one that cannot safely be ignored.

The Egypt mine reopened in 1888 and ran continuously through 1902 after sizeable gas explosions in 1895 and 1900, and financial difficulties once again forced closure. In 1915, Norfolk Southern Railroad obtained the property and ran the mine under the name of Cumnock Coal Company, the word Egypt having become synonymous with explosions and failures. The company supplied coal primarily for railroad purposes and was a small operation. In September 1922 the Erskine Ramsey Coal Company purchased the company with plans to significantly enlarge the enterprise and its output. Around 1921, the Carolina Coal Company developed a mine on the site of the old Farmville village on the Chatham County side of the Deep River, less than two miles east of the Cumnock Mine.

There is some confusion over the name of the event. The News and Observer called the event the “Cumnock Mine Disaster” in its initial coverage and a negative envelope in the Ben Dixon McNeill Collection carries the same title. The Cumnock Mine, however, was not the mine where the accident occurred. Farmville was later renamed Coalglen, or alternately Coal Glen at a date not readily available. The disaster has since been referred to in association of one of these three nearby locations. The dateline in the New York Times is from Coal Glen.

Printed Sources:

“Red Sand Stone Formation of North Carolina: Extract of a letter from Professor D. Olmstead, of the College at Chapel-Hill, North-Carolina, dated Feb 26, 1820.” American Journal of Science, 2:1 (April 1820), 175-176.

Wilkes, Charles. Report on the Examination of the Deep River District, North Carolina. Caption title: Report of the Secretary of the Navy, communicating the report of officers appointed by him to make the examination of the iron, coal and timber of the Deep River country, in the state of North Carolina, required by a resolution of the Senate. [Washington, 1859.]

Report on an Exploration of the Coal Fields of North Carolina: made for the State Board of Agriculture. Raleigh, N. C.: P. M. Hale, state printer and binder, 1885.

Campbell, Marius R. and Kent W. Kimball. The Deep River Coal Field of North Carolina. Prepared by United States Geological Survey, in cooperation with the North Carolina Geological and Economic Survey, 1923.

Coal Deposits in the Deep River Field, Chatham, Lee, and Moore Counties, N.C.: Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1952.

Reinemund, John A. Geology of the Deep River Coal Field, North Carolina. Washington, D. C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1955.

World Wide Web Sources:

Margaret Wicker: The Coal Glen Mine Disaster

Image Source:

News & Observer. [Raleigh, N.C.] 29 May 1925.

Photographs cropped as they appeared in the newspaper. Originals in the Ben Dixon McNeill Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, North Carolina Collection, Photographic Archives.