This Month in North Carolina History

On March 16, 1916, North Carolina shore-based whalers caught and killed their last whale in the shallows off Cape Lookout. The last shore-based crew in the area disbanded the next year, after their gear was destroyed by a fire. These events marked the end of more than 250 years of tradition. Although whaling was never a major operation in North Carolina, the unique geography of the state and the tenacity of its residents allowed a small whaling industry to operate from colonial times through the early 20th century.

The earliest North Carolina whaling was not about catching whales, but rather was about processing whales that had already beached themselves or otherwise became stranded near the shore. Later, fishermen all along the East Coast developed shore-based systems of capturing and killing whales using teams of small boats. New England and New York fishermen—the main American whalers—gradually evolved their technique into a famous and extremely profitable ship-based industry. Whaling ships left from ports like New Bedford and Nantucket and hunted on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans until the industry’s demise in the mid-1920s. North Carolinians, however, held to the older tradition, and after 1800 it was the only state south of New York truly participating in a shore-based whaling industry.

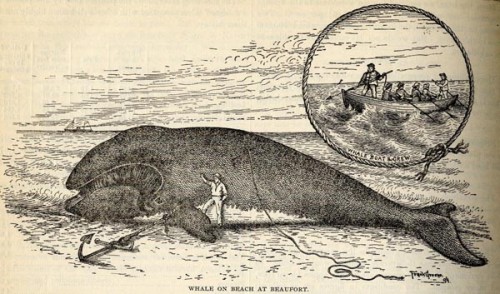

North Carolina whaling activities centered on Beaufort, with the most active crews operating off Cape Lookout and Shackleford Banks. These particular locations were ideal because they were very close to both the Gulf Stream and the regular migration paths of several types of whales. The season generally ran from late December to early June, with the peak coming sometime between February and May, when the whales migrated northward for the summer. Whalers spent the rest of the year in other endeavors, such as mullet or porpoise fishing. The number of men and the profitability of their whaling varied greatly from year-to-year. For example, R. Edward Earll reported that in 1879 there were four camps with a total of 72 men on the North Carolina coast. They took five whales and sold their products for $4,000. The next year, however, they missed the main migration and 108 men only caught one small whale for a sales total of $408.46. Because whale hunting was a cooperative endeavor, the profit made was divided among the men on a share basis, with about 30 to 45 shares for an 18-man crew. Each man received one share, gunners drew an extra share, and steersmen received an extra half share. In addition, for each gun he provided a man would get an extra two shares. A boat entitled a man to one additional share, and a full set of harpoons and lances was worth about 2/3 of a share.

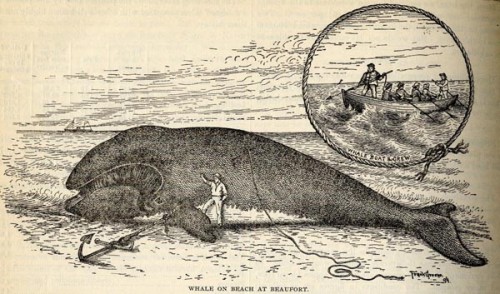

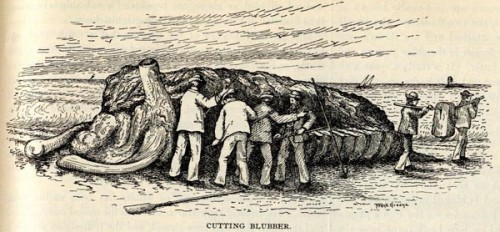

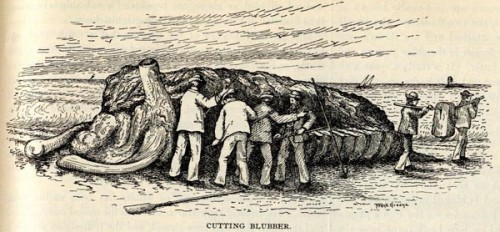

A relatively detailed description of the North Carolina system of whaling was written by R. Edward Earll in the early 1880s for a federal document about the nation’s fishing industries. At the beginning of the season the whalers would build a camp on the shore that included huts or shelters from the weather and a “crow’s nest” or other type of lookout station on a hill. The station would be constantly manned. When the lookout spotted a whale, he would signal the camp and men would set out in their row boats in pursuit. Upon catching up with the animal, the men would harpoon it, usually with a wooden weight attached to the harpoon. The whale generally attempted to flee, but the drag from the weight would tire it. When it slowed or turned to fight the boats, a gunner would shoot it. In many cases, the men would initially target a calf, knowing that they were slower than the adults and that its mother would stay behind to help it. Early whalers used lances and harpoons to kill their prey, but the post-Civil War years also saw the use of specially-designed whale guns that shot explosive cartridges filled with a quarter pound of gunpowder. After it was killed, the whale’s carcass would be towed to shore. It was then cut apart and the blubber was processed or “tried out.”

There were generally two types of whales targeted by North Carolina crews: right whales—so-called because they were considered the “right” type of whales to hunt—and sperm whales. Both types yielded blubber, as well as fat from tongue, tail, skin, and flukes. These portions of the whale were processed into oil used as a fuel and a lubricant. The flexible baleens of right whales (which they used to filter food from the water) were utilized in a wide variety of products, including women’s corsets and umbrella ribs. Sperm whales produced two unique and very expensive materials. From their heads, whalers collected a very high quality wax/oil called spermaceti which was used in high-quality candles. In their digestive systems sperm whales created ambergris, a natural by-product that was used as a fragrance and fixative in perfumes. After the harvest of these parts, the bulk of the whale was discarded.

Whaling was serious and dangerous business, but Shackleford had one particularly unique and whimsical tradition: the residents named many of the animals they caught. “George Washington Whale” was captured on the president’s birthday, “Little Children Whale” was chased and killed by boys from the community when the adults were otherwise occupied, and “Cold Sunday” was taken on a day that was reportedly cold enough to freeze ducks in mid-flight. Perhaps the most famous of the state’s whales is “Mayflower,” a fifty-foot right whale killed in 1874. The whale is notorious for its final fight; it capsized one boat and dragged another between six and eight miles out to sea before it died. Its fame continued to spread after its death when its skeleton was put on display in the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in the 1880s. (You can still visit Mayflower today in the Raleigh museum.)

The general downfall of whaling was caused by a combination of factors including the over-hunting of whales and the change in women’s fashions that nearly eliminated the need for whale-bone corsets. North Carolina’s whaling industry was also greatly damaged by particularly bad weather on the Outer Banks. Several large storms on Shackleford in the 1890s followed by a hurricane in 1899 prompted the population to abandon the area for safer locations on the mainland or more sheltered islands.

After the last whale was caught and the last crew disbanded, the occasional beached whale would be processed on North Carolina beaches. New England whaling ships also continued to hunt their quarry in North Carolina waters. In fact, they sent ships to the Hatteras Grounds, far off the northeast corner of North Carolina’s coast, until 1925.

Sources

H. H. Brimley. “Whale Fishing in North Carolina,” in Bulletin of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, 14 (April 1894).

“North Carolina and its Fisheries” in George Brown Goode. The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1887.

Marcus B. Simpson, Jr. and Sallie W. Simpson. Whaling on the North Carolina Coast. Raleigh: Division of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1990.

David Stick. The North Carolina Outer Banks 1584-1958. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1958.

William Henry Tripp. There Goes Flukes. New Bedford: Reynolds Printing, 1938.

Image Source:

H. H. Brimley. “Whale Fishing in North Carolina,” in Bulletin of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, 14 (April 1894).